(CNN) – Ukraine’s first President, waiting to see America’s 41st, chatted with a White House press aide — in Ukrainian. George H.W. Bush’s deputy secretary of state didn’t need to hear more.

“I know where I’m sending you,” Lawrence Eagleburger told the press aide, Roman Popadiuk.

That’s how Popadiuk, born in Austria to displaced Ukrainians who then immigrated to America, in 1992 became the first US ambassador to Ukraine following the breakup of the Soviet Union. The experience placed him on the ground floor of relations between the two nations over three decades preceding today’s allied efforts to help Ukraine fend off Russian aggression.

And he offers a blunt verdict on the US government’s performance during that time: “I think we handled it wrong from the get-go.”

That’s not a partisan statement. Popadiuk spent his career not as a political appointee but as a foreign service officer.

He has a quintessentially American story.

His family, assisted by a Catholic charity, ended up in Brooklyn after a brief stint on an Iowa farm. In 1959, when Popadiuk was 9 years old, an immigration official handed him a citizenship certificate for his adopted country just before Thanksgiving.

“He said, ‘Do you like turkey?’ ” Popadiuk recalls with a chuckle. ” ‘You’re an American.’ ”

A Ph.D. in international affairs and a foreign service exam later, he wound up detailed to a nonpolitical job in

President Ronald Reagan’s White House. Press secretary Larry Speakes ended up making Popadiuk his deputy for international affairs, a job he held into the next administration until Bush sent him to Kyiv.

After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the US lavished diplomatic attention on Russia to encourage economic modernization and security cooperation from its former Cold War adversary. Former Soviet republics such as Ukraine, Popadiuk says, didn’t get nearly enough

As ambassador, he initiated discussions over what became known as the Budapest Memorandum. Under its terms, Ukraine surrendered a large nuclear arsenal within its borders in return for security assurances from Russia, the US and Britain.

Ukraine’s concession was less than met the eye, since Russia had retained the nuclear launch codes for those weapons. But Popadiuk says the fledgling government in Kyiv should have gotten more US economic and military aid.

Other errors followed, flowing largely from the impulse to maintain a positive US-Russia relationship. President George W. Bush, who famously said he had peered into Vladimir Putin’s soul, reacted cautiously to Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia. President Barack Obama, who sought a “reset” with the Kremlin, did the same after Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine.

“Both administrations fell short in realizing the threat,” Popadiuk concludes.

President Donald Trump exacerbated domestic divisions that Putin has counted on to weaken America’s response to his aggression. That included Trump’s own impeachment over his attempt to squeeze Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for political favors.

But Popadiuk doesn’t think Trump’s presidency fundamentally affected Putin’s calculations. Nor does he blame President Bill Clinton’s support for expanding the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to include Ukraine, among other nations in Eastern Europe.

Russia’s historic desire to control Ukraine, he explains, runs deeper than any of those developments. That’s why he faults President Joe Biden, who released so much accurate intelligence about Putin’s intention before the war, for not acting on it by preemptively providing more military aid.

“If you knew they were going to attack Ukraine, why didn’t you give them everything they needed ahead of time?” Popadiuk says. “We needed to get ahead of him.”

The bravery of Ukraine’s soldiers and ineptness of his own appear to have caught Putin by surprise. So has the unity that Biden and his European counterparts have maintained.

But Popadiuk says the allied response remains too constrained by fear of nuclear escalation. NATO hasn’t transferred old Soviet fighter jets to Ukraine, for example, to avoid the possibility of Russia attacking the transfer and compelling a NATO response.

“We’ve let Putin define the rules of the game,” he explains, rather than making the risk of a catastrophic exchange the Russian leader’s burden.

Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian civilians have grown more savage as its military falls short of its objectives. Last week brought a missile strike at a train station in Kramatorsk, on top of attacks on hospitals and executions on the streets of Bucha.

The more they happen, the stiffer the test of allied resistance to direct confrontation with Russia through steps such as a NATO-imposed no-fly zone.

“There’s got to be a red line for the West,” says Popadiuk. The objective is imposing a price high enough to shift Putin’s cost-benefit analysis.

An ugly end is already assured. Distasteful as it would be, he fears halting the conflict will eventually require recognizing Russian control over Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine.

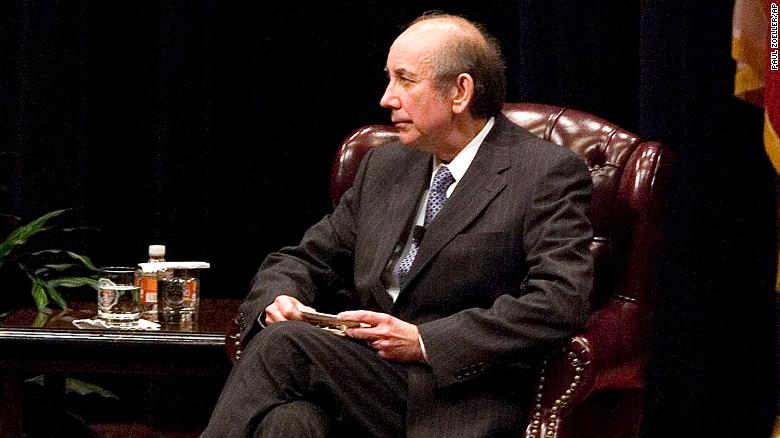

At 71, Popadiuk is long removed from any active role in foreign policy. He retired ten years ago as diplomat-in-residence at the George H.W. Bush Foundation, which like Bush’s presidential library is at Texas A&M University.

What Popadiuk knows for certain is that, whatever America and its European allies do, Ukrainians won’t stop defending their country.

“This is about a cultural war of survival for Ukrainians,” he says. “If there’s one standing, that fight’s going to go on.”