The German parliament will decide Thursday on the fate of the vast Stasi archive, with critics warning against jeopardizing its critical work 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

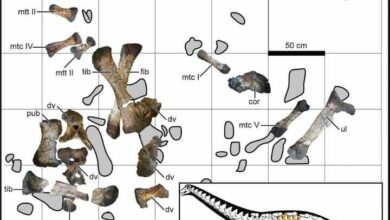

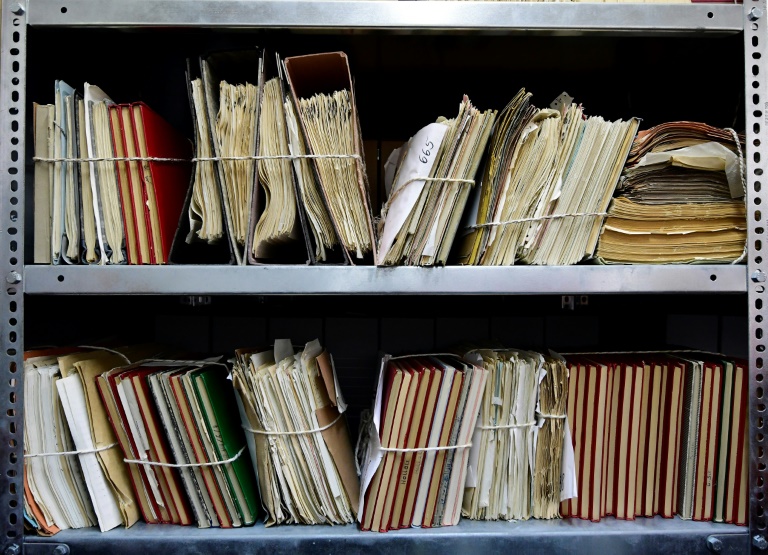

Deputies will vote on whether to integrate the Stasi records and its 111 kilometres (69 miles) of files collected by the hated secret police into the Federal Archives.

Access to the files would be kept open, said Roland Jahn, Special Commissioner for the Stasi Records.

The measure is part of a bill to restructure the archive’s management.

Jahn said the move, set for summer 2021, would secure the future of the files as the national archive offers necessary expertise and infrastructure for preserving and digitiztraing documents.

Once among the world’s most tightly controlled states, communist East Germany (GDR) deployed Stasi police and used citizen informers to spy on the population, documenting their movements and actions in the millions of files found today in the archive.

Critics of the restructuring plan fear the institution would be swallowed up by the broader Federal Archive, leading to a cut in funding and ultimately hurting the crucial service it provides in the process of coming to terms with the former East Germany’s communist past.

Hubertus Knabe, a historian and former head of the memorial at the Stasi’s prison in the Hohenschoenhausen district, warned that “what will change is that the largest institution for dealing with the GDR past will no longer exist after 2021”.

That would have “consequences that are not negligible for all educational programmes” on the issue, he wrote in Welt daily.

Werner Schulz, a former dissident who is now a Green party MEP, said the move was “premature”, voicing fears that “a lid will be put on history here”.

‘Fit for the future’

In the chaos following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Stasi employees rushed to destroy their secret files, initially shredding them but as the machines broke down under the strain, they began to tear documents by hand.

The waste was to be pulped or burnt but “citizen committees” stormed Stasi offices across East Germany, seizing millions of files along with 15,500 bags of torn-up documents.

Following reunification in 1990, a Special Commissioner for the Stasi Records was swiftly appointed to safeguard the hoard while also ensuring that people have access to files that concern them.

The Aufarbeitungsverein Buergerkomitee 15. Januar, an association that helps Stasi victims come to terms with the past, said the independent status of the commissioner and the archives must never be compromised.

Calling on parliament to suspend the decision on Thursday, it warned that placing the records within the Federal Archives risks integrating them under a political structure that ultimately answers to the government.

“There are fears that information on oversight as well as the viewing of the files” could be subject to political whims, warned the organisation named after the January 15, 1990 date when the Stasi headquarters in East Berlin was stormed.

Embarrassing information could be kept under wraps, it argued.

But Jahn said the changes were principally aimed at making the archive “fit for the future as we can tap the expertise, technology and resources under the roof of the Federal Archives”.

Asked if the restructuring was the wrong move on a key anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Jahn told broadcaster Deutschlandfunk: “Quite the opposite.”

“We are sending the message that on the 30th anniversary of the peaceful revolution, we have this symbol of the peaceful revolution — that is, the access to the files and the possibility to use them — and that is something that we are securing permanently.

“This is a step into the future. We want to do away with the fixation on the topic of state security. We don’t want an agency for absolute truth… rather we want a Stasi archive that makes documents readily available, so that a discussion can take place in society,” he said.