In a new medical breakthrough for 3D printing, US doctors have saved the lives of three children with a fatal airway disease by creating personalized implants that their bodies can absorb.

Three babies who were on the brink of death from tracheobronchomalacia, an incurable disorder which causes the windpipe to collapse, were given airway splints that allowed them to recover and breathe freely, said the research published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

While not yet approved by US regulators, the personalized devices, created by means of 3D-printing, were given an emergency medical exemption and are still considered high-risk.

Kaiba Gionfriddo, the first child to undergo the procedure, was three months old when he had the surgery. Now he is a healthy three-year-old who attends preschool, researchers said.

The other two boys were five months and 16 months old when they had the surgery. They also continue to do well and have suffered no complications.

"This is the first cure of this condition," said senior author Glenn Green, associate professor of pediatric otolaryngology of the University of Michigan's C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

About one in 2,000 children are affected by tracheobronchomalacia worldwide, Green said. Unable to exhale fully, the children's windpipes are prone to collapse, and the only treatment is sedation and intensive care. However, infections and complications are common and Green described the children's life expectancy as "grim."

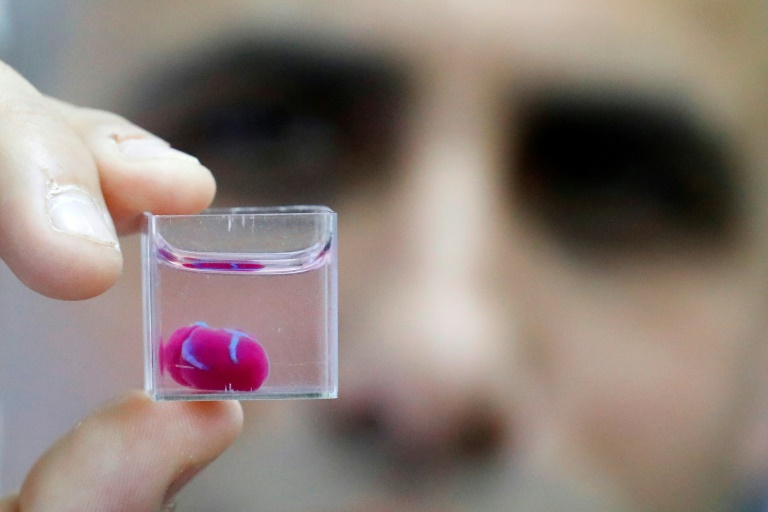

Researchers used CT scans of the children's airways to create a personalized implant, made of biomaterials and designed to expand, almost like a butterfly clip, as they grew.

"The printed splints were hollow and porous tubes that could be sutured over the affected airways and were made of polycaprolactone, a polymer that harmlessly dissolves in the body," said the study.

The process of designing and printing an implant took between one and three days.

The technology may eventually make it easier to treat rare disorders that have been neglected by medical device companies due to high investments costs, said co-author Scott Hollister.

"You can address patient niche markets that wouldn't have been addressable with the previous manufacturing technologies," Hollister said.

Another advantage to the approach was that doctors were able to print the trachea and bronchi beforehand, and practice the operation before the actual surgery on the children.

"This ends up saving significant amounts of time. It helps us to be much more precise than was possible previously," Green said.

"I look at this as one of the biggest changes that is happening in surgery as we speak."

A clinical trial including some 30 children is planned to begin soon.

Hearing aids, dental implants, stents and prosthetics have also been made with 3-D printing.