India’s tycoons are playing a pivotal role in the Asian giant’s most expensive election ever, from funding campaigns and tacit endorsements to being hot-button issues themselves.

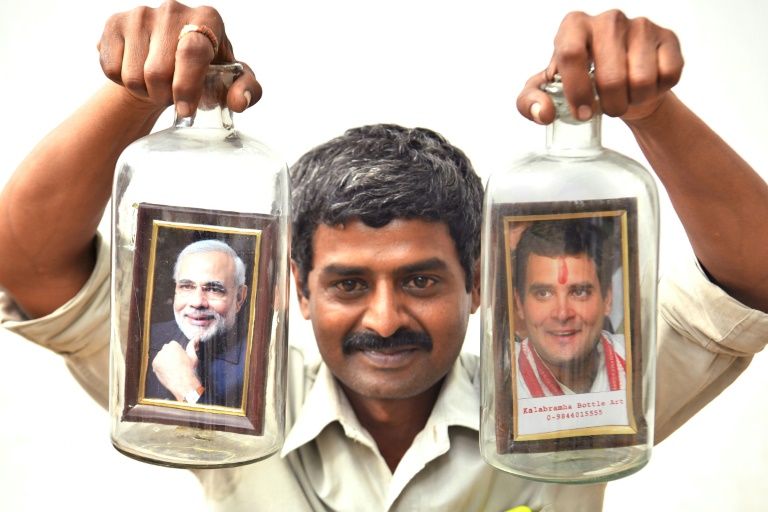

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s re-election bid has received huge financial backing from corporate India, raising fears about the integrity of the world’s largest democratic process, experts say.

Meanwhile, Congress party opponent Rahul Gandhi is trying to exploit a fighter jet deal involving industrialist Anil Ambani while fugitive tycoons Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi loom over the vote from London.

Contesting polls is getting costlier in India and analysts say parties are becoming more reliant on donations from anonymous businessmen, leading to a lack of transparency and worrying conflicts of interest.

“There’s a trend towards plutocracy,” Niranjan Sahoo, of the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) think-tank, told AFP. “Unbridled corporate influence can have a serious impact on policies,” he added.

The New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies estimates that around $5 billion was spent during the 2014 election that swept Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power — up from $2 billion in 2009.

The group thinks the 2019 contest could top $7 billion, making it one of the priciest elections globally.

“Elections are getting more expensive for many structural reasons,” Milan Vaishnav, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace think-tank, told AFP.

“(There is a) growing population, increasing political competition, voter expectations of handouts in the form of cash and other inducements, and technological change, which means greater outlays for media and digital outreach,” he added.

Analysts say traditional funding streams, such as party memberships, are declining so parties increasingly rely on wealthy donors to fund campaigns.

Data compiled by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), an election watchdog, showed that in financial year 2017-18 corporates and individuals contributed 12 times more to the BJP than to six other national parties, including Congress, combined.

‘Quid pro quo’

The BJP received 93 percent of all donations above 20,000 rupees ($290) that year, according to ADR’S analysis. Modi’s BJP banked 4.37 billion rupees ($63.3 million); Congress got just 267 million rupees.

“There is a huge funding disparity now. Congress simply doesn’t have the money to fight elections. That should worry people,” said the ORF’s Sahoo.

Modi’s government says it has cracked down on so-called “black money” in politics by lowering the amount that can be donated in cash from 20,000 rupees to 2,000 rupees.

Critics, however, say it is now easier for wealthy entities to donate to political parties; corporate funding formed 92 percent of the total donations declared by the BJP in 2017-18, according to ADR.

Detractors point to the government removing a cap on corporate donations two years ago and introducing a scheme whereby donors can give anonymously through “electoral bonds” purchased from a bank.

On Friday India’s supreme court ordered parties to reveal the identity of donors after activists challenged the bond system, which the government has defended.

“The lack of transparency allows conflicts of interest and quid pro quos to flourish”, said Vaishnav, who suspects that medium-sized businesses requiring permits from the government are more of an issue than India’s big oligarchs.

Tycoons do not explicitly endorse candidates for fear of backing the wrong horse but Modi, 68, is seen to be close to several big tycoons.

In 2014 he traveled between rallies in a corporate jet and helicopter owned by billionaire industrialist Gautam Adani, while magnate Ratan Tata praised Modi for carrying out air strikes in Pakistan.

India’s richest man Mukesh Ambani — whose personal net worth has soared from $18.6 billion when Modi came to power to $53 billion today, according to Forbes — has repeatedly called him “our beloved prime minister” in speeches.

‘He’s not the messiah…’

“If you look at the measure that counts, which is how much money do these guys have, then India’s tycoons have done tremendously well under Modi,” James Crabtree, author of “The Billionaire Raj”, told AFP.

Ambani’s oil-to-telecoms conglomerate Reliance Industries and the Adani Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Gandhi, 48, is trying to score political points by accusing Modi and Anil Ambani, Mukesh’s younger brother, of dodgy dealings related to the purchase of Rafale jets from France –- allegations both deny.

Congress’s leader is also using liquor-baron Mallya and jeweller Nirav Modi to attack the BJP. The government accuses them of massive fraud and is trying to extradite them from Britain.

Modi pledged to crack down on crony capitalism during his tenure so the duo represent a sore point for a man who prides himself on being India’s “chowkidar” (“watchman”).

“Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi have become the symbols of a job half done. Nonetheless the noose is tightening on these guys,” said Crabtree.

India’s business community appears less enthusiastic about Modi this time round after a shock cancellation of high-value banknotes and poorly implemented new tax disrupted economic growth.

But they are set to vote for him overwhelmingly anyway, fearing that a coalition or Gandhi victory could put a halt to much-needed economic reforms.

“He’s not the messiah we thought he was but without doubt almost everybody wants Modi to come back with an absolute majority,” said a prominent Mumbai-based businessman who asked not to be named.

“Because beyond him there is no alternative,” he added.