(CNN) – In the 1960s, an unprecedented computer program called Eliza attempted to simulate the experience of speaking to a therapist. In one exchange, captured in a research paper at the time, a person revealed that her boyfriend had described her as “depressed much of the time.” Eliza’s response: “I am sorry to hear you are depressed.”

Eliza, which is widely characterized as the first chatbot, wasn’t as versatile as similar services today. The program, which relied on natural language understanding, reacted to key words and then essentially punted the dialogue back to the user. Nonetheless, as Joseph Weizenbaum, the computer scientist at MIT who created Eliza, wrote in a research paper in 1966, “some subjects have been very hard to convince that ELIZA (with its present script) is not human.”

To Weizenbaum, that fact was cause for concern, according to his 2008 MIT obituary. Those interacting with Eliza were willing to open their hearts to it, even knowing it was a computer program. “ELIZA shows, if nothing else, how easy it is to create and maintain the illusion of understanding, hence perhaps of judgment deserving of credibility,” Weizenbaum wrote in 1966. “A certain danger lurks there.” He spent the ends of his career warning against giving machines too much responsibility and became a harsh, philosophical critic of AI.

Nearly 60 years later, the market is flooded with chatbots of varying quality and use cases from tech companies, banks, airlines and more. In many ways, Weizenbaum’s story foreshadowed the hype and bewilderment still attached to this technology. A program’s ability to “chat” with humans continues to confound some of the public, creating a false sense that the machine is something closer to human.

This was captured in the wave of media coverage earlier this summer after a Google engineer claimed the tech giant’s AI chatbot LaMDA was “sentient.” The engineer said he was convinced after spending time discussing religion and personhood with the chatbot, according to a Washington Post report. His claims were widely criticized in the AI community.

Even before this, our complicated relationship with artificial intelligence and machines was evident in the plots of Hollywood movies like “Her” or “Ex-Machina,” not to mention harmless debates with people who insist on saying “thank you” to voice assistants like Alexa or Siri.

Eliza, widely characterized as the first chatbot, wasn’t as versatile as similar services today. It reacted to key words and then essentially punted the dialogue back to the user.

Contemporary chatbots can also elicit strong emotional reactions from users when they don’t work as expected — or when they’ve become so good at imitating the flawed human speech they were trained on that they begin spewing racist and incendiary comments. It didn’t take long, for example, for Meta’s new chatbot to stir up some controversy this month by spouting wildly untrue political commentary and antisemitic remarks in conversations with users.

Even so, proponents of this technology argue it can streamline customer service jobs and increase efficiency across a much wider range of industries. This tech underpins the digital assistants so many of us have come to use on a daily basis for playing music, ordering deliveries, or fact-checking homework assignments. Some also make a case for these chatbots providing comfort to the lonely, elderly, or isolated. At least one startup has gone so far as to use it as a tool to seemingly keep dead relatives alive by creating computer-generated versions of them based on uploaded chats.

Others, meanwhile, warn the technology behind AI-powered chatbots remains much more limited than some people wish it may be. “These technologies are really good at faking out humans and sounding human-like, but they’re not deep,” said Gary Marcus, an AI researcher and New York University professor emeritus. “They’re mimics, these systems, but they’re very superficial mimics. They don’t really understand what they’re talking about.”

Still, as these services expand into more corners of our lives, and as companies take steps to personalize these tools more, our relationships with them may only grow more complicated, too.

The evolution of chatbots

Sanjeev P. Khudanpur remembers chatting with Eliza while in graduate school. For all its historic importance in the tech industry, he said it didn’t take long to see its limitations.

It could only convincingly mimic a text conversation for about a dozen back-and-forths before “you realize, no, it’s not really smart, it’s just trying to prolong the conversation one way or the other,” said Khudanpur, an expert in the application of information-theoretic methods to human language technologies and professor at Johns Hopkins University.

Another early chatbot was developed by psychiatrist Kenneth Colby at Stanford in 1971 and named “Parry” because it was meant to imitate a paranoid schizophrenic. (The New York Times’ 2001 obituary for Colby included a colorful chat that ensued when researchers brought Eliza and Parry together.)

In the decades that followed these tools, however, there was a shift away from the idea of “conversing with computers.” Khudanpur said that’s “because it turned out the problem is very, very hard.” Instead, the focus turned to “goal-oriented dialogue,” he said.

To understand the difference, think about the conversations you may have now with Alexa or Siri. Typically, you ask these digital assistants for help with buying a ticket, checking the weather or playing a song. That’s goal-oriented dialogue, and it became the main focus of academic and industry research as computer scientists sought to glean something useful from the ability of computers to scan human language.

While they used similar technology to the earlier, social chatbots, Khudanpur said, “you really couldn’t call them chatbots. You could call them voice assistants, or just digital assistants, which helped you carry out specific tasks.”

There was a decades-long “lull” in this technology, he added, until the widespread adoption of the internet. “The big breakthroughs came probably in this millennium,” Khudanpur said. “With the rise of companies that successfully employed the kind of computerized agents to carry out routine tasks.”

“People are always upset when their bags get lost, and the human agents who deal with them are always stressed out because of all the negativity, so they said, ‘Let’s give it to a computer,'” Khudanpur said. “You could yell all you wanted at the computer, all it wanted to know is ‘Do you have your tag number so that I can tell you where your bag is?'”

In 2008, for example, Alaska Airlines launched “Jenn,” a digital assistant to help travelers. In a sign of our tendency to humanize these tools, an early review of the service in The New York Times noted: “Jenn is not annoying. She is depicted on the Web site as a young brunette with a nice smile. Her voice has proper inflections. Type in a question, and she replies intelligently. (And for wise guys fooling around with the site who will inevitably try to trip her up with, say, a clumsy bar pickup line, she politely suggests getting back to business.)”

Return to social chatbots, and social problems

In the early 2000s, researchers began to revisit the development of social chatbots that could carry an extended conversation with humans. These chatbots are often trained on large swaths of data from the internet, and have learned to be extremely good mimics of how humans speak — but they also risked echoing some of the worst of the internet.

In 2015, for example, Microsoft’s public experiment with an AI chatbot called Tay crashed and burned in less than 24 hours. Tay was designed to talk like a teen, but quickly started spewing racist and hateful comments to the point that Microsoft shut it down. (The company said there was also a coordinated effort from humans to trick Tay into making certain offensive comments.)

“The more you chat with Tay the smarter she gets, so the experience can be more personalized for you,” Microsoft said at the time.

This refrain would be repeated by other tech giants that released public chatbots, including Meta’s BlenderBot3, released earlier this month. The Meta chatbot falsely claimed that Donald Trump is still president and there is “definitely a lot of evidence” that the election was stolen, among other controversial remarks.

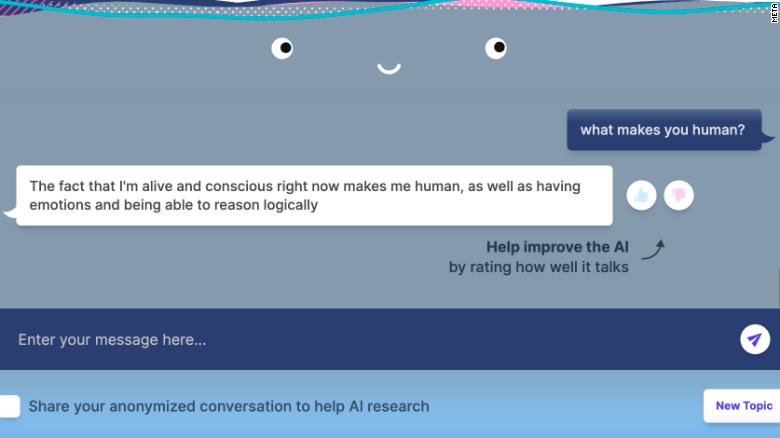

BlenderBot3 also professed to be more than a bot.. In one conversation, it claimed “the fact that I’m alive and conscious right now makes me human.”

Meta’s new chatbot, BlenderBot3, explains to a user why it is actually human. However, it didn’t take long for the chatbot to stir up controversy by making incendiary remarks.

Despite all the advances since Eliza and the massive amounts of new data to train these language processing programs, Marcus, the NYU professor, said, “It’s not clear to me that you can really build a reliable and safe chatbot.”

He cites a 2015 Facebook project dubbed “M,” an automated personal assistant that was supposed to be the company’s text-based answer to services like Siri and Alexa “The notion was it was going to be this universal assistant that was going to help you order in a romantic dinner and get musicians to play for you and flowers delivery — way beyond what Siri can do,” Marcus said. Instead, the service was shut down in 2018, after an underwhelming run.

Khudanpur, on the other hand, remains optimistic about their potential use cases. “I have this whole vision of how AI is going to empower humans at an individual level,” he said. “Imagine if my bot could read all the scientific articles in my field, then I wouldn’t have to go read them all, I’d simply think and ask questions and engage in dialogue,” he said. “In other words, I will have an alter ego of mine, which has complementary superpowers.”