Salloum–Egypt’s western frontier is home to 750,000 Bedouins from the Awlad Ali tribe. While the neighboring Libyan east ceded to revolutionaries who overcame attacks from incumbent dictator Muammar al-Qadhafi, the tribesmen of Egypt hail the revolt, despite contested histories of affiliation.

The Awlad Ali tribesmen fled to Egypt’s Western Desert some 500 years ago after they were ousted from the Libyan Desert by their adversaries. Today they are located on a stretch of land that starts at the Libyan-Egyptian border and extends 500 kilometers eastward.

With the Libyan revolt successfully spread to the Eastern cities of Benghazi, al-Baida and Tubruq by the brothers and cousins of Awlad Ali’s tribe of Egypt, the tribe’s reaction is in question.

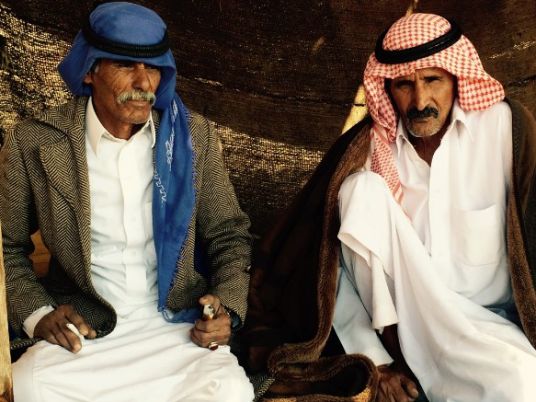

Asked whether Awlad Ali’s tribesmen would cross to join the fighting between Pro-Qadhafi men and the revolutionaries, Basset Abul Zalat, a Bedouin from the Western Desert, answered with the logic of modern states.

“It’s an internal issue. We cannot intervene,” said the middle-aged man, who lives in the coastal city of Marsa Matrouh.

However, beyond the modern state, there are better established tribal relations. “We can only intervene if asked by the Ebeidat tribes,” he said. The Ebeidat are relatives of Awlad Ali whose territory begins near the Libyan city of Benghazi and spreads 600 kilometers to the Egyptian border.

Awlad Ali’s involvement in Libyan wars, fighting alongside their brethren next door, is fact in history. For one, Awlad Ali’s men fought the Italian colonizers with their fellow tribesmen until 1947. More recently, they also fought next to their Libyan counterparts against Chadian-French forces between 1978 and 1987, a battle primarily initiated by Qadhafi’s interest in annexing the bordering northern tip of Chad.

In the current unrest, some media reported that Ahmed Qadhaf al-Dam, a cousin, top security aide of Qadhafi and mediator of the Egyptian-Libyan relations, fled to Egypt’s Western Desert to collect tribesmen to fight the revolutionaries.

Qadhaf al-Dam is a figure known to the Awlad Ali tribe and engages some of them in his Egyptian real estate and tourism investments in the Western Desert. On the onset, he was introduced to Libyan-Egyptian politics when Qadhafi resorted to Egyptian mediation in his recent rapprochement with the U.S. after long years of hostility, according to Awlad Ali accounts.

But allegations of Qadhaf al-Dam’s collecting tribal mercenaries from Awlad Ali sounded like an insult to many of them. “It didn’t happen and it won’t happen,” insisted Abul Zalat.

Fellow tribesman Hamad Khalid, who works for the Ministry of Culture, denounced such media reports “as they treat Bedouin tribesmen as sheep with no brain.”

He used the same tribal logic that Abul Zalat referenced to showcase the falsity of such claims. “What ties our tribes together is much stronger that what ties a state together. It is inconceivable that a tribesman in Egypt kills his brother in Libya. In fact it is the political regime in Libya and its repressive apparatuses that make us revert to our tribal links and prioritize them.”

Abul Zalat said that Qadhaf al-Dam did arrive in the area recently, but headed to Fayoum where he has closer relatives. According to him, there is a small group of Bedouins who live on his money. Qadhaf al-Dam tried to pay them to help the Libyan regime reconsolidate its grip on the east, “but the Egyptian authorities knew of the deal and aborted it,” Abul Zalat said.

On Thursday, the Associated Press and other media reported that Qadhaf al-Dam condemned the blood bath in Libya and was seeking political asylum in Egypt.

The Bedouins of the Western Desert related their accusation of being bought to become Qadhafi’s mercenaries to their own plight in Egypt.

“We have been racially discriminated against in Egypt and always called traitors,” Abul Zalat said with bitterness.

He said that most of the tribesmen are not admitted in the military service and the few who get conscripted are not given arms, but only secondary service jobs, an issue repeatedly voiced by the Bedouins of Sinai as well.

Abul Zalat also spoke of how the Awlad Ali are deprived of the benefits of the thriving oil and tourism industries in the Western Desert and coastal area, with jobs mostly going to Egyptians from the Delta and Cairo. Land ownership is another contested issue–Bedouins claim a de facto ownership by virtue of having lived there for hundreds of years, while they are legally denied the ability to register these lands in their names.

Mamdouh Doubali, a tribesman from Awlad Ali, traced this mistreatment to a longstanding belief by the Egyptian government that the tribes’ loyalty leans towards Qadhafi.

“It all goes back to Qadhafi’s interest in the Western Desert. In 1974, he called it ‘the eastern desert of Libya’ and he recurrently spoke of his state as extending ‘from the desert to the desert’. Throughout the 1970s, he managed to coerce a lot of tribesmen who became loyal to him and his money,” he said.

These relations made the Egyptian regime wary of the Western Desert and its tribesmen. “The security apparatus became particularly repressive because they treated us all as Qadhafi’s men,” he added.

The security’s repression followed the formation of a revolutionary group in the Western Desert supported by Qadhafi, according to Abul Zalat. The group, which operated from 1974 until the early 1980s, was reportedly inspired by South Yemen and Latin America’s revolutionary movements. It embarked on small-scale militant operations in Egypt such as a bombing in Tahrir Square.

Qadhafi supported the group amid hype of hostility with Egypt, which had made peace with Israel in 1978. This resulted in an Egyptian-Libyan conflict that lasted for a decade and ended with reconciliation. The Bedouin movement was quelled with an Egyptian-Libyan agreement that stipulates Qadhafi must refrain from supporting any groups in Egypt.

Nowadays, the tribesmen of Awlad Ali vow their state loyalty to Egypt. The 25 January uprising further consolidated this choice.

“We are the first to side with the Egyptian revolution and we acted as its guardians and mobilizers in the west,” Doubali said.

Abul Zalat traveled to Cairo’s Tahrir Square, where strikes and protests since 25 January became the face of the Egyptian revolt. For him, the Egyptian revolution resonated with the aspirations Awlad Ali’s tribes for a better life.

“Regardless of the political setting that defines us, our priority is justice and equality,” Abul Zalat insisted.