Egyptian novelist and ex-diplomat, Ezzedine Choukri Fishere, seems to be taking his literary career to new heights with his latest novel, “Embrace on Brooklyn Bridge,” one free of binary categorizations and judgments.

Fishere had written four novels that portray the gradual collapse of the Egyptian state in a rapidly changing international landscape, where terrorist groups and political Islam are on the rise. He would often focus on the persistence of despotic rulers, and offer a Kafkaesque view of the real world. Through “The Killing of Fakhredine” (1995), “Pharaonic Journeys” (1999), “Intensive Care Unit” (2009) and “Abu Omar al-Masry” (2010), Fishere successfully fleshed out diverse characters.

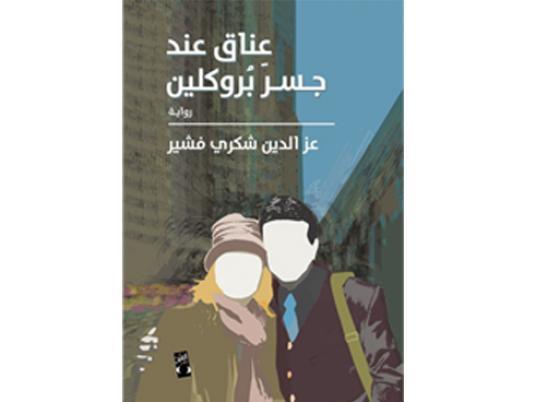

In 2011, he released “Embrace on Brooklyn Bridge,” published by Dar al-Ain and long-listed for the 2012 Arabic Booker prize. In his fifth novel to date, he breaks away from his stylistic anchors. According to Fishere, his previous four novels were seen as attempts to decipher the complicated and secret worlds of terrorism.

In “Embrace on Brooklyn Bridge,” Fishere tackles many of his previous themes, yet in more abstract ways, using personal narratives of the eight main characters, all of whom are on their way to a dinner party hosted by the protagonist, Darwish, in New York City.

Having found out that he is dying with no more than two years to live, Darwish wants to reconnect with family, friends and acquaintances he acquired while living in the US. But he refuses to tell anyone about his disease, not even his daughter Laila and son Youssef. Instead, he asks Laila, who moved back to Egypt, to send over his 20-year-old granddaughter, Salma, to stay with him; he plans to throw her a party. For him, this is the best way to say goodbye to his loved ones.

The story starts off introducing Darwish, and one senses a melodrama and sensational beginning. It gets more interesting halfway through, when we are introduced to the other characters who travel across states to make it to Salma’s birthday party. We never know what happens at the party; however, it’s the journey that is most interesting. And readers get to pick their own protagonists among novel’s eight characters. They may choose from idealistic Youssef or the hot tempered Rabab, who defends minority rights, or Loccman, by far the easiest character to identify with, someone who doesn’t draw sympathy but rather interest. It is his love story with the Dutch Marick that Fishere decided to name the book after.

“Embrace on Brooklyn Bridge” is a story about hope and frustration, search for justice and meaning in life, the futile pursuit of perfection, dismantling the binaries of East and West, and right and wrong. Devastated by nostalgia and estrangement, the characters recount their experiences roaming among airports and train stations. Some stories happen in Holland and New York, while others take place in Sudan and Egypt. We hear invitees recounting classic stories vilifying the West. Others express frustration with their failure to blend into western societies.

Limited success in belonging to any community is a common concern for many of Fishere’s characters. There is the repeated story of Arab intellectuals unable to adapt to their home countries, and hence they fly across the world to find a new home in the Big Apple and its many universities. In this case we have Darwish being a stark example. Young generations oscillate between sham patriotic and religious discourses on one hand, and a cruel discriminatory reality on the other.

Every character in the book seems imprisoned by his own worldview. Although many of the narratives intersect, Fishere allows no one to speak about others’ experiences. Amidst personal stories, the reader becomes unable to distinguish between real incidents and subjective perceptions, a conscious decision by Fishere to dismiss all attempts at reaching a unifying interpretation.

The pleasant surprise in novels of that sort is that most of Fishere’s characters defy expectations.