In a spacious newsroom divided by pillars, reporters, focused on their computers, sit at a round table. Around the corner, some colleagues have removed their shoes and lined up for noon prayers.

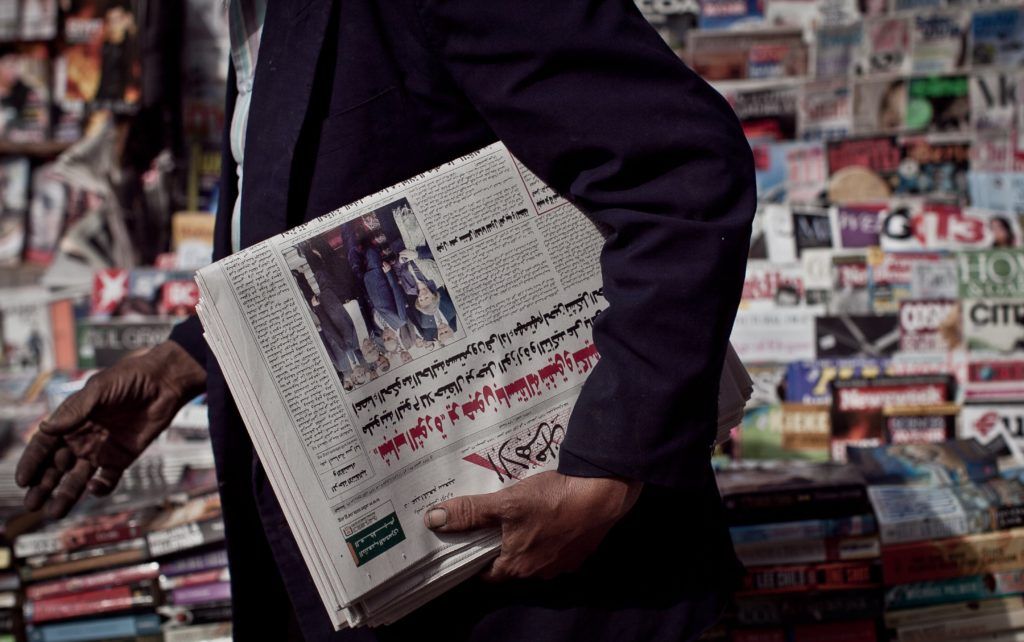

Meanwhile, Mohamed Mostafa, one of the paper’s four managing editors, roams the office in socks and slippers and holding proofs of the next day’s issue.

It is one of his busiest days, Mostafa tells Egypt Independent. It is his turn to oversee the production process of the nascent Freedom and Justice, the official newspaper of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP).

A year ago, it would have been inconceivable for Egypt’s oldest Islamist organization to openly issue its own daily paper. Now, a year after the outbreak of the January revolution and the ouster of former President Hosni Mubarak, the FJP seems poised to dominate the coming parliament. This ascent has been accompanied by the group’s investments in a media empire that they hope will build bridges to a larger audience and bolster the Brotherhood’s political leverage. In recent months, the group has tapped into print and broadcast media by launching a satellite channel in addition to the Freedom and Justice daily.

Beyond propaganda?

“From day one, the paper’s editorial policy has sought to address all readers,” says 31-year-old Mostafa, who sports a light beard.

“The paper is not only the FJP voice and does not only address readers who belong to the Muslim Brotherhood,” explains Mostafa, a founding member of the FJP and a 13-year member of the Muslim Brotherhood. He assures that not all the staff shares his background.

“More than 70 percent of those who work at the paper belong neither to the Muslim Brotherhood nor the FJP,” says Mostafa, who used to work for the investigative journalism department at the state-owned newspaper Al-Akhbar.

To explain the paper’s editorial position, the Cairo University graduate borrows the same discourse of the group’s stalwarts, arguing that the Freedom and Justice paper, which shares the name of the Muslim Brotherhood’s party, stands as a venue to promote a “renaissance-oriented project” based on a moderate interpretation of Islam.

Nevertheless, the paper, which first hit newsstands in late October, appears to be a platform for the Muslim Brotherhood to market its positions on contentious political issues and rebut charges leveled against Islamists.

In November, the paper spearheaded opposition to calls made by some secular groups to postpone parliamentary elections until violence had subsided.

Other content has echoed the group’s resistance to the military’s attempts to circumvent the roadmap for the transition period in a way that could weaken Islamist parties.

While Mostafa insists that his paper seeks to downplay divisions between political forces and emphasize points of agreement, observers argue otherwise.

“The discourse is not objective,” says Ashraf al-Sherif, an expert on the group. “[The paper] carries attacks on other political forces.”

“The discourse is similar to that of the NDP [Mubarak’s former ruling party]. It accuses whoever disagrees with the Muslim Brotherhood of bad faith.”

Recently, the paper has been attempting to shed light on the “third party” that the military holds responsible for violence on Qasr al-Aini Street earlier this month. On Sunday, the paper dedicated almost a full page to discussing the ideology of “anarchist forces” that seek to undermine the Egyptian state.

The paper is preoccupied with promoting political stability, according to Sherif.

In the midst of the ongoing parliamentary race, Freedom and Justice can also serve as a crucial campaign tool. On an almost daily basis, the paper runs lengthy interviews with FJP parliamentary candidates. It has recently devoted full pages to highlighting FJP ideas on housing, education and other issues, though Sherif still believes that the paper falls short of advancing sophisticated policy prescriptions.

Since its inception, the 83-year-old Islamist organization has sought to use the media for outreach. In 1933, the Muslim Brotherhood issued “Majallat al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin,” or “The Muslim Brotherhood Magazine,” its first weekly news publication. Until Gamal Abdel Nasser’s clampdown on the group in the 1950s, the Brotherhood released other publications under different names, such as Al-Nadhir, Al-Mabahith and Majallet al-Da’wa. After Anwar Sadat released jailed brothers and allowed the group to operate again, the monthly magazine Da’wa was issued in the 1970s.

Mubarak’s regime was inconsistent in its treatment of the group, at times loosening its grip on the Brotherhood and allowing members to create their own publications before cracking down and censoring them. To evade the regime control, the group resorted to cyberspace. In 2001, it launched its official website Ikhwan Online and five years later the English-language website Ikhwan Web. Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated sites and blogs mushroomed from there.

The Brothers hit the waves

The end of the Mubarak era encouraged a group of Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated businessmen to launch Misr25, a satellite television channel, in May. The channel has a general interest format with a special emphasis on news programming. Three news bulletins are aired throughout the day and five minute news briefs are transmitted at the top of the hour. A rolling news ticker is updated continuously.

Hazem Ghorab, the channel’s director, insists that Misr25 is not a Muslim Brotherhood mouthpiece. “I cannot and would not engage in partisan journalism. Before I joined, I made it conditional that the ownership be separated from the management of the channel,” says Ghorab, who is neither an FJP nor a Brotherhood member, but admits that he supports the group.

“I said that even the Supreme Guide [the Muslim Brotherhood’s highest official] will not be able to interfere,” adds 59-year-old Ghorab, who previously worked for Al-Jazeera and a Japanese television station.

Like most of its competitors, the channel invests in news talk shows. Most of these feature politicians and pundits known for their sympathy with political Islamic groups and who attempt to diffuse fears of the Islamists’ ascent to power. For the brothers, secular channels inherently hostile to Islamist groups constantly feed those fears.

According to Safwat al-Alem, a professor at Cairo University’s Mass Communication School, the Brotherhood — like its liberal counterparts — has the right to tap into broadcast media. He points out that Wafd Party head Al-Sayed al-Badawy owns the Hayat channel and Naguib Sawiris, the founder of the Free Egyptians Party, owns ONTV.

“Today, they have the right to have a channel,” says Alem, speaking of the Muslim Brothers. “After the results of the first parliamentary round, a war was waged against them and their candidates, so they have the right to reply to the propaganda.”

Sherif says there is more to it than countering the liberals. The Brotherhood also wants to challenge the Salafi “media empire.”

For years, Mubarak’s regime allowed Salafi satellite channels to grow, while Salafi groups remained aloof from politics, supported the status quo and showed hostility to the Muslim Brotherhood.

After the revolution, the Salafis emerged as an adversary of the Muslim Brotherhood. In the ongoing elections, the Salafi Nour Party and the FJP are competing for the same Islamist constituency. In the first round, the FJP ranked first, garnering 40 percent of the votes while the Nour Party emerged as a surprise runner-up with 25 percent. In the second round, the results were similar.

A traditional touch

Misr25 reflects the Brotherhood’s conservative social outlook. The channel’s female correspondents and anchors have to abide by an Islamic dress code. Wearing a hijab, long-sleeve jackets and almost no makeup, women go on air reading the news, reviewing the press and hosting guests.

“Our Islamic identity says that a woman should dress modestly and the headscarf is part of this modesty,” says Ghorab, accusing other channels of succumbing to Western culture when they let unveiled anchors wearing “sleeveless” or “décolleté” shirts appear on TV, or when they air drama shows that do not conform to Islamic culture.

But the decision to show women on television at all may mark progress for the group.

“We had a problem showing women’s pictures on the site. Even pictures of veiled women were hard to show in the beginning,” says Abdel Galeel al-Sharnouby, former editor of Ikhwan Online and a former Muslim Brother. He adds that the group was also reluctant to use music.

The Freedom and Justice daily has covered cinema, culture and music in an attempt to challenge stereotypes about the group’s disapproval of various art forms. Still, the coverage has flirted with Islamic conservatism by running interviews with veiled singers or actresses.

But Mostafa argues that their culture pages are engaging with artistic content that does not necessarily bear conservative undertones; he points out that the paper reviews comedy movies.

“We don’t judge art by moral values but by artistic values,” he says, adding that the only moral restrictions art pages should observe is to refrain from displaying “inappropriate” pictures.

“I won’t run inappropriate pictures to prove that I’m open-minded,” says Mostafa. The daily's editorial policy, he argues, resonates with the moral standards of a society where the majority is “inherently religious.”