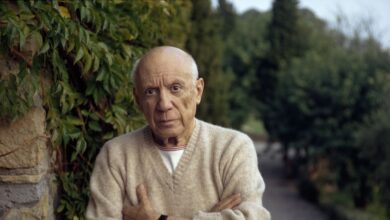

Everything about George Bahgory recalls a lost time. The renowned Egyptian painter and caricaturist (sometimes referred to as the “Grandaddy of Egyptian Caricature”) has cultivated for himself the classic image of a 19th century Parisian painter; mustachioed, with a pointy beard, and a painterly hat at a jaunty angle. Bahgory seems to lead the romantic life of the intellectual observer, moving back and forth every half-year from Cairo, to Paris, to Cairo, and back.

The figures that haunt his artistic imagination are those of generations past; he is a follower of Picasso who worships Om Kalthoum, who once would share a downtown café table with Naguib Mahfouz. Bahgory lives in the grand tradition of the artist flâneur — the urban stroller, lounger and observer who, in his leisurely way, takes in the city as it buzzes about him, portraying the people of the urban tableau, full of lively cafés and bread sellers sailing through downtown alleyways. “I have a crowd in almost every painting,” Bahgory told Egypt Independent.

Bahgory spent 2011, as he has spent many of his years, painting downtown Cairo, where he lives and works when he is not in Paris. This past year, of course, the streets often fell into a different kind of chaos from the everyday jumble of shops and people and dust and traffic, chaos less conducive to contemplative observation. But Bahgory kept an attentive eye on this upheaval. “It was very interesting to find my people shouting,” he says, “I sleep hearing their voices.”

“Bahgory on Revolution,” a collection of these latest works, is currently on display at the Masar Gallery in Zamalek, timed to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the 25 January revolution.

Bahgory’s Cairo is colorful and romantic. It is hard to pin a time on the people and places that fill his vibrant depictions, which flatten out and twist dimensions in the Cubist style of his idol Pablo Picasso. Though Bahgory’s most recent work takes on the most overwhelming and present subject of the contemporary moment, he still works with timeless imagery, choosing cafes, camels and street musicians as his emblems of upheaval, along with flashes of the obligatory Egyptian flag.

Bahgory’s speedy drawing style (“I don’t like discipline,” he says) is fitting for depiction of the heaving masses of Tahrir Square. On less violent days of the uprising, the 80-year-old artist spent time in the square sketching, and still goes from time to time. But the event that he devotes the most canvas to in “Bahgory on Revolution” took place on one of the most violent and notorious of the 18 days. The Battle of the Camels features in the pair of pieces “Battle of the Camels I & II” as well as in the grand, wall-sized canvas “The True Path (Tahrir Square).”

The latter work exemplifies how painting, typically a medium of high art and slow response, can capture the movement and emotion of even a familiar and contemporary moment more effectively than straightforward photography. Bahgory’s wild canvas layers paper and fabric over a writhing crowd, a thick mass of drawing and collage, in which a flailing horse and camel fall headlong into the teaming, wailing sea of people. The piece evokes the terror and absurdity of that infamous day more effectively than most of the more documentary representations that have been in such ample supply in recent months.

The subject of revolution often drums up strong iconography and bombastic feeling in artists who choose to represent it. Though in a recent interview with Ahram Weekly, Bahgory cited “Guernica,” Picasso’s gut-wrenching series of drawings on the Spanish Civil War, as an inspiration for his work on the revolution in Egypt, the sketches and paintings at Masar are much more joyful and triumphant than that earlier, more tragic collection. Despite the panic apparent in “The True Path (Tahrir Square),” its title imbues it with revolutionary grandeur, and the collection also includes the seemingly requisite ode to nationalism “Proud Egyptian,” a collaged portrait of a voluptuous, haloed woman in peasant dress, the accents of her clothes taken from fabric featuring a distinctively Egyptian pattern.

While “Guernica” was a project in documenting suffering, Bahgory’s revolutionary paintings serve more to glorify than to mourn, and so veer away from tragedy toward imagery of populist triumph. Still, Bahgory’s is an honest emotional response that channels and amplifies the energy of those early revolutionary days more effectively than much other work produced in response to the same events.

Bahgory writes in his text for the exhibition, “My own screams have become the canvases that you see in this exhibition.” But despite its emotional strength, all his work is steeped in nostalgia. “Bahgory on Revolution” includes a room of portraits in Bahgory’s signature painted style, walking a fine line between expressive abstraction and pure caricature. The selection includes two new portraits of Om Kalthoum, long a favorite subject of the painter, and a portrait of Sheikh Imam, the legendary singer whose late 1960s revolution-themed songs have seen a revival in the context of this current revolutionary moment. Bahgory cannot let go of those looming icons of the past. But even when he paints the violent, triumphant, tumultuous Cairo of 2011, what emerges on the canvas is a timeless Egypt, of camels, horses, shisha and peasant-dress, where signs of modernity — of 2011 — are almost completely absent. Still, Bahgory’s colors vibrate on the canvas, and I believe him when he says, “My five fingers have turned to hot red, orange and yellow… mirroring the flames around me.”

“Bahgory on Revolution” will be on view at Al Masar Gallery, Baehler's Mansion, 157B, 26 July Street, Zamalek, Cairo, until 17 February. The gallery is open from 11:00 am to 9:00 pm, Saturday through Thursday.