I know Mohamed Mahmoud Street quite well, albeit in more tempered times. I used to traipse back and forth down it while a student at the American University in Cairo. This is not meant as an introduction to a piece about Mohamed Mahmoud through the eyes of an AUC-ian, merely to point out that it is a street I am familiar with, by virtue of having attended a university whose two main buildings lined the street.

Admittedly, it was off-putting to see tear gas crack through the glass of what used to be the university library last November during the first of the Mohamed Mahmoud clashes, but the street has become much more than just the path between one classroom and another. It’s become the main locale for a fight, both real and symbolic, over this country, interrupted by concrete walls and shattered shop facades.

Depending on your mood — inspired or despondent — Mohamed Mahmoud is a street of struggle, of great bravery in the face of a heavily armed adversary, of sacrifice, not just of life but also of limbs, of eyes. It is also a street of death, of senseless loss, of blood spilt that is yet to be paid for. The murderers get away time and time again.

The latest stand against the system that this particular street witnessed came last month, in the wake of the Port Said Stadium massacre, in which over 70 football fans were killed. Clashes erupted downtown the following day; again Mohamed Mahmoud became the center point that extended to the intersecting streets of Mansour, Fahmy and Noubar.

This time, while the fighting was ongoing, a group of artists decided to start work on the AUC wall at the beginning of the street. That wall already had much graffiti on it, but this latest batch took it one step further — painting on the existing graffiti, painting new images, and the work hasn’t stopped since.

What has arisen as a result is a loosely connected mural of death and mourning. A commemoration of the many lives lost, their images on the wall resplendent, vibrant with a life they once had. It’s interesting that the many faces of the deceased are portrayed in expressions of downright cheekiness, eyes bursting with life.

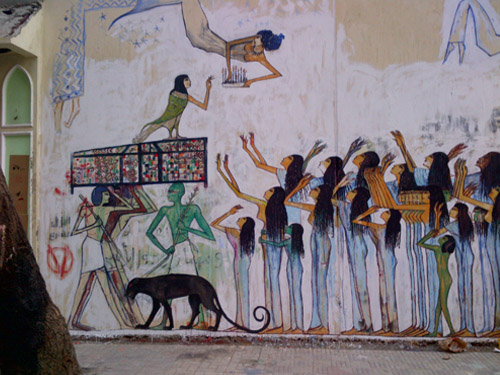

The work is split into panels that comprise sections of the wall. The central one is entitled “Glory to the martyrs” and has faces of those killed at the ill-fated match and on Mohamed Mahmoud. Surrounding it are a number of Pharaonic depictions of burials and wailing and mourning. Preceding them at the corner of the street with Qasr al-Aini is a huge painting of a split-face Tantawi and Mubarak, which was done by an artist not working on the mural, Omar Fathy, but it inadvertently serves as a great introduction. “Walk on and see our handiwork,” it seems to say.

The murals on the street proper are the work of four artists, Ammar Abu Bakr, Alaa Awad, Hana al-Deghem and Mohamed Khaled. Abu Bakr and Awad are demonstrators at the University of Fine Arts. Abu Bakr is responsible for the martyrs’ panel, while Awad did the Pharaonic scenes.

Abu Bakr is representative of many a revolution supporter in Egypt who seems to have reached the end of his tether by the amount of death that has gone unanswered for.

“Talking has died,” he says.

He seems frustrated, belligerent, angry. I can relate. So he paints, and theorizes when prompted: “We don’t need these generations,” he says of the those in power, “the teenagers and those in their twenties are much smarter than all of those who are sitting on chairs under the dome of Parliament or anywhere else.”

And so the four have continued their work on the wall, despite continued harassment from authorities and passersby. But aside from the politics, there is also an artistic message the group aims to spread. They’re trying to draw a connection between the graffiti that has exploded post-25 January and the traditional Egyptian art of wall painting. “Egyptians have always painted on walls,” Abu Bakr says.

Awad talks me through the Pharaonic funeral that he has painted. The people carrying the coffin are the Egyptian people, the green man symbolizes immortality, the black panther with the red eyes denotes anger, and the black flowers express sorrow and anger at how they died. Despite depicting death, Awad insists that Mohamed Mahmoud is “a street of life and freedom” and that’s the message he feels is coming out from the work to the world.

While the group painted over the existing graffiti and did use stencils in some of the work, specifically the martyrs whose images Abu Bakr pulled off the internet, much of the painting is freehand, such as Awad’s Pharaonic depictions.

Another interesting image is of Sambo, the young man who is still detained after the initial Mohamed Mahmoud clashes of November, for having wrestled a rifle from a policeman, which he never used. The rifle is painted in four different cheerful colors, with three empty and equally colorful speech bubbles around him. He has a rifle in one hand and his other arm is outstretched — it is taken from a famous picture of him. Again it resonates with the rest of the work as it comes before the martyr’s panel. He seems to be saying, “Come and see, my brothers who have fallen.”

While I am there, a woman comes with a painting she has done that she wants to hang up. The painting — a hodgepodge of tiny images — has one of a soldier hand in hand with a citizen. Abu Bakr curtly tells the woman to go find a place to hang the painting in Abbasseya, the area where the pro-SCAF groupies tend to gather. An argument ensues; the woman eventually goes on her way.

And I too go on my way, walking out of Mohamed Mahmoud, a street that to me was where I bought my cigarettes, did my photocopying and walked to and from the metro station, and later became a street in which I choked from tear gas, saw policemen shoot at protesters from close range and saw the military fire strange swirling fireballs that lit up the night. A street I once thought I knew so well.