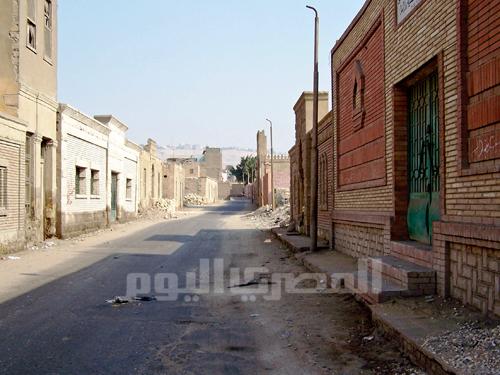

Habibah has many reasons to feel fortunate. Unlike most of Cairo's residents, she does not have to share her home. She does not have to put up with slamming doors or screaming babies or boots on concrete stairs. On her street it is quiet enough to hear birdsong. Obviously, this is something people in affluent districts like Maadi or Zamalek can claim. But in some respects Habibah is doing better than them. She did not buy her house, has no mortgage, and has paid no rent for over three decades. The only problem where she lives is that most of her neighbours are dead.

Habibah has lived in a tomb in Cairo's vast southern cemetery since the late 1970s. "At the time, my mother-in-law was living here. When my husband died, I came to stay with her." When I asked if she likes the neighborhood, she nodded. "It's quiet, and I am away from problems, and with God."

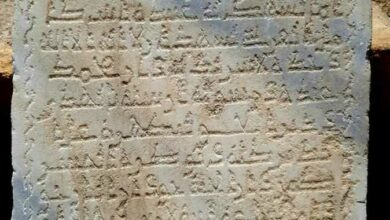

Cairo's cemeteries have been home to the living for thousands of years. Until the 20th century, their population was small and mainly consisted of tomb attendants and pilgrims to the many shrines and madrasas the graveyards contain. The massive increase in Cairo's population during the last century — which has doubled since the 1960s — coupled with economic hardship, rural migration and the effects of the 1992 earthquake, has made it hard to find affordable housing, forcing people to find alternatives. The population of Cairo's cemeteries has been estimated at around 100,000.

As for how one makes a tomb into a home, it takes few structural changes — like most of them, Habibah's was a single-storey stone building with a good roof. The actual graves were in a back yard beneath mango and guava trees. All that was needed was to partition the space into rooms and cupboards. The government has installed electricity and water taps in the cemeteries, though sewage disposal is still a problem. Habibah's tomb has no bathing facilities, so she goes to visit her sister-in-law in Dar al-Salam, a half-hour bus ride away.

When I asked if she is scared to stay there on her own at night, it was not for superstitious reasons: many have reported a rise in street crime since the 25 January revolution. Habibah said she was not worried, but that sometimes her grandson sleeps there. "He brings me most of the things I need, and I know many of the young people here, and they help me, because I was like a mother to most of them." Later I saw some of them playing football at the end of her street. The goals were large, almost regulation-size; their nets were made from intertwined pieces of wire.

Habibah's nearest living neighbor, a woman named Mesi, lives ten tombs down the street. Mesi's story is similar to Habibah's. After her husband died in a car crash in 1982 she came to live with her sister-in-law, who a few years later went back to a village in Upper Egypt where she had relatives. Unlike Habibah, she has to pay a small amount of rent to the relatives of those buried inside. The majority of the other residents I spoke to had also been living in the cemetery a long time. The only recent arrival I met was a sour-faced man who stared at the earth while describing how his house had burnt down during the first 18 days of the revolution. After speaking for 20 seconds, he put out his hand and asked for money.

Habibah had just offered me a glass of tea when the chicken-seller arrived. He was in his late fifties, possibly older; he looked tired, and with good reason. While Habibah was boiling water he told me that most days he got on a truck before dawn with several others from his village. After being dropped in the nearby district of Manshiyet Nasser, he walks round with the cage on his head, trying to find buyers, until the truck takes him back at dusk. At the start of most days the cage contains 12 to 15 birds; on that day, at four o'clock, there were still nine birds inside.

When Habibah came out she put down our tea, looked at the birds, and pointed. "Let me see that one," she said. The man reached in and took out a small one with black feathers that had orange flecks. As chickens went, it was unimpressive. It was hard to believe the seller's assurances that it would grow up to be a great egg-layer. There was a pinched quality to the bird's features; it looked somewhat frail.

"Bring me a better one on Monday," said Habibah, and the man, without arguing, put the little bird back. I asked how much it was. "Ten" he said, and for a moment I thought of buying all his stock and giving them to Habibah. "That's too much," she said and laughed. The chicken-seller drank his tea quickly, then stood and said goodbye. He walked away as quickly as you can with a cage of live birds on your head. Perhaps he could sell a few more.

I asked Habibah what she thought of the revolution. She clapped her hands together and said she thought it was very good. She only had one reservation. "I wanted it to murder Mubarak and all of the others. They have got too fat in prison. This is what they need," she said and mimed strangling them. Then she laughed delightedly and repeated the gesture.

I asked if she had voted in the elections. "Yes, because otherwise I would be fined LE500. When I went the Islamists gave me a piece of paper to show me how to vote. But I don't know if I did. I just made a mark on the paper then left."

We drank our tea then went to look at the tombs in her yard. There were three of them and they did not look very old. I asked Habibah what she knew about the people buried inside. The sense of her reply was cryptic, or just lost in translation. "Not a lot, but I know them because I stay with them. Their relations come every year and they are very good people."

The last thing I asked, because it was dusk, and I'm frightened of graveyards at night, was whether she planned to keep living in the tomb.

"Yes," she said. "I want to be buried here."