The list of candidates for Egypt’s next president was finalized on Tuesday evening when the Presidential Elections Commission (PEC) announced that the appeals against disqualification of 10 potential candidates, including several possible frontrunners, had been rejected. As Egypt moves towards the first round of elections on 23 and 24 May, 13 candidates remain.

But legal experts raise questions about whether the decisions made by the PEC, composed of five senior judges, are consistent with Egyptian law and internationally recognized legal norms. Instead, it may have been political considerations that led to the disqualification of Omar Suleiman, Hosni Mubarak’s intelligence chief and vice president; Hazem Salah Abu Ismail, a Salafi preacher and lawyer; Khairat al-Shater, a Muslim Brotherhood leader; and Ayman Nour, a liberal politician from the Ghad al-Thawra Party.

Abu Ismail is now accusing the PEC of fraud and he and his supporters have staged a sit-in in front of the PEC’s headquarters. Shater, in a press conference on Wednesday, spurned his dismissal, harshly criticizing the Supreme Council of Armed Forces for backing a candidate who belongs to the old regime and intending to rig the elections in his favor, referring to candidate Ahmed Shafiq, a former Mubarak-era minister.

But Shater and Abu Ismail’s concerns won’t get them anywhere. There is no legal avenue for appealing the PEC’s decisions. According to Article 28 of the SCAF-issued Constitutional Declaration, the PEC’s decisions are final and binding. This lack of legal transparency leaves room for politically motivated decision making, says Mohamed Hamed al-Gamal, a former head of the State Council.

“Nothing can prove the authenticity and legality of the committee’s decisions because no other party can judge the documents or the proof upon which they based their decision,” Gamal told Egypt Independent, adding that Article 28 contradicts Article 21 of the same document, which prohibits giving legal immunity to any administrative decision.

To add further suspicion, legal experts say there are clear loopholes in all of the decisions disqualifying the major candidates.

Hazem Salah Abu Ismail

Abu Ismail, who enjoys a fiercely dedicated following and an active campaign, was disqualified from the race because of allegations that his late mother had US citizenship, violating stipulations laid out in the Constitutional Declaration and approved in a popular referendum in March of last year.

Ibrahim Darwish, a professor of constitutional law, finds the commission’s claim that Abu Ismail’s mother held US citizenship unconvincing. An Administrative Court’s ruling last week stated that all the documents submitted by the Interior Ministry contained no proof of any foreign nationality even though the commission said it received documents from the Interior Ministry indicating that Abu Ismail’s mother had entered Egypt on a US passport before.

When the PEC issued the disqualification decision, it said it received official documents from the US Department of State a day after the court’s ruling that prove Abu Ismail’s mother obtained US citizenship on 25 October 2006. Abu Ismail, however, questioned the authenticity of the papers and denounced the decision as part of a conspiracy.

“We don’t have anything that proves these claims [that Abu Ismail’s mother held US citizenship],” said Darwish, condemning the lack of transparency surrounding the decision.

Atef al-Banna, a professor of constitutional law at Cairo University seconded Darwish’s reservations. Moreover, Banna said, photocopies of official papers cannot be used as legal evidence and documents from foreign countries alone cannot serve as evidence without being supplemented by corresponding local ones.

Omar Suleiman

The PEC ruled out the former spymaster because he was 31 endorsements short of the minimum 1,000 required from 15 discrete governorates. Suleiman’s campaigners said that they had the endorsements ready and signed before the deadline, but the commission refused to accept them after the nomination period ended.

Darwish says the commission should have accepted the 31 missing signatures, especially because they were made on a date before the deadline for nomination.

“31 endorsements represent a minimal percentage of the 30,000 required from each candidate, which doesn’t affect the end result,” said Darwish, basing his argument on Article 24 of the Egyptian Procedure Act 13 (1968).

“What is the use of allowing candidates to appeal their disqualification then?” Darwish says.

Banna, however, considers submitting late signatures a violation of the principle of equal opportunity between all candidates and so he agrees with this disqualification.

Suleiman said on Wednesday that he respects the committee’s decision and won’t challenge it.

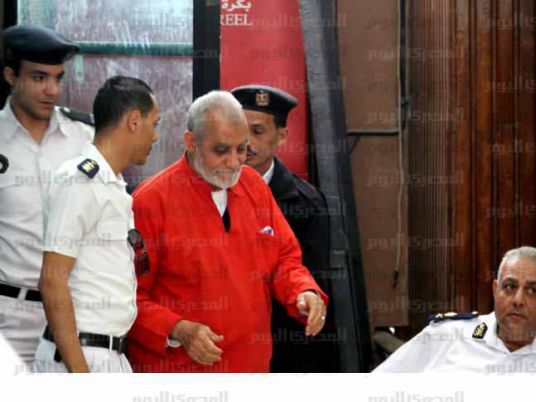

Khairat al-Shater

Shater’s nomination was rejected on the grounds that he has not completed a prison sentence.

According to the PEC, Shater received a court pardon for a 1995 military case in which he was sentenced to five years in jail on charges of "reviving" the Muslim Brotherhood, then an illegal organization. However, the PEC said that the pardon didn’t absolve Shater of the 2007 charges against him of providing university students with arms and training. In the 2007 case, a military court sentenced him to seven years for terrorism and money laundering.

Shater’s lawyer Abdel Moneim Abdel Maqsoud said in a phone interview with ONTV Tuesday that he submitted a document issued from the military court that confirms his client is pardoned from both cases. “All the commission’s decisions are politicized and they didn’t adhere to the provisions of the law. Manipulation of the elections started from today,” Abdel Maqsoud said.

Darwish agrees. “It looked like the commission set a trap for Shater,” he said. “They should have told him at the time when he was submitting the nomination papers so that he had time to get the document before the nomination deadline closed.”

Ayman Nour

Nour was disqualified on the same grounds as Shater. In 2005, after he ran for president against Mubarak, Nour was charged with forging endorsements to establish a political party in a trial that was widely viewed as a means of crushing Mubarak’s opposition.

Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi, the head of the SCAF, recently issued Nour a pardon and restored his full political rights. However, the PEC said that a SCAF pardon doesn’t fulfill the legal conditions to allow him to run for the presidency. He still needs a court decision to approve his candidacy.

Banna challenges the decision, saying that besides the fact that it was known that Nour’s conviction was politically motivated to prevent him from competing with Mubarak, Tantawi’s pardon cancels out the verdict, as well as its consequences, such as limiting his ability to run for president.

“Tantawi’s pardon is stronger and more comprehensive than a court’s pardon from a legal point of view, which means [Nour] satisfies the conditions to run for the presidency,” Banna says.

Last Saturday, an administrative court ruled that Nour is not eligible to run because of his previous convictions and requested that the pardon be revoked. Banna, however, rejected the Administrative Court’s jurisdiction to rule in that matter.

So why?

But if the PEC’s uncontestable and less-than-transparent decisions raise questions among legal scholars, some political analysts have an explanation: the commission’s decisions are part of the SCAF’s plans to manipulate the outcome of the presidential election.

Abdel Halim Qandeel, a prominent political columnist, believes that the Suleiman disqualification was simply a cover for the PEC to knock the two most prominent Islamists out of the race, at the SCAF’s request.

Suleiman had announced his candidacy at the last minute, on the heels of a heated debate between the Muslim Brotherhood and the SCAF. He collected most of his endorsements within 48 hours.

Qandeel says Suleiman’s short-lived candidacy was just a test balloon and a way to antagonize the Muslim Brotherhood. For him, Suleiman’s disqualification is the least convincing of all 10, but leaving Suleiman while rejecting the others would have enraged Islamists.

“It was necessary for the SCAF to withdraw Suleiman from the race in return for withdrawing the two Islamist candidates in order to make it look neutral,” Qandeel said.