As Nile resources dwindle and Egypt’s population rises, groundwater could form an important part of a strategy to cope with an expected sharp increase in demand for water, experts say.

With an estimated 55 million more people by 2050, and continuous challenges from countries upriver to Egypt’s Nile use rights, experts say the vast underground aquifers in the Western Desert and other regions could buffer against future water stress, as well as alleviate effects of climate change in the coming years.

“Groundwater has been an invisible resource, with many uncertainties in the parameters and factors affecting its ability to be used,” said Amr Abdel-Megeed, the regional water specialist at the Center for Environment and Development for the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE).

As Egypt faces further water stress, Abdel-Megeed says, the government will have to diversify its water sources beyond the Nile.

“Groundwater is already part of the plan, but there’s also treated wastewater and desalination that will have to be utilized,” he said.

Egypt shares access to one of the world’s largest fossil water reserves. The vast Nubian Sandstone Aquifer system spans across Sudan, Chad, Libya and Egypt, and reaches Sinai and southern Israel to the northeast.

A non-renewable resource, the aquifer is composed of fossil water that was accumulated over thousands of years and has received no recharge water for the last 4,000 years. Its resources feed the New Valley agriculture projects at Kharga, Dakhla, Farafra and Bahareya.

Egypt also has other aquifers in the Eastern Desert and Sinai, the Nile Basin, the Mediterranean coastal zones and Wadi al-Natrun.

While some experts estimate that the aquifer could support current usage for hundreds of years, Abdel-Megeed urges caution.

“This sources aquifer is non-renewable, so any exploitation, over-exploitation or mis-utilization affects the reserves,” he said, adding that there must be “rational utilization” that avoids using the water for agriculture, unless it is for high-value, low water-consuming crops.

In the last 50 years, various government programs have resettled millions of Delta and Nile Valley farmers, university graduates and state employees whose companies have been privatized into the reclaimed desert farming communities in the Sahara.

Such desert plots now account for about 25 percent of the country’s agricultural land, according to the American University in Cairo’s Desert Development Center. These settlements rely on groundwater to irrigate their fields.

The resource is already dwindling. Wells that relied on natural springs have now installed pumps to help bring the water to surface.

“The big projects started in the 1960s in Egypt and in the 1970s in Libya affected the water that had been naturally flowing in the surrounding oases,” said Abdel-Megeed, adding that “with big projects that started, the level of groundwater has been drawn down so that now people use pumps over the springs to draw water up.”

Facing growing pressure from Nile Basin countries to renegotiate the 1959 colonial-era treaty that gave Egypt rights to most of the Nile’s resources, some experts warn that similar allocation issues could occur over the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer in the future.

According to Sameh S. Ahmed, a professor of environmental engineering at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia, it’s likely in the next two decades that Egypt, Chad, Libya and Sudan will have to create an agreement over usage rights of the aquifer.

“There is a need for an agreement in form of convention [or] treaty between the four countries similar to what is used in distribution of the Nile,” he said.

The governments are already cooperating on research. The Joint Authority for the Study and Development of the Nubian Sandstone is working to create cooperation strategies and raise money for research projects.

The authority, which consists of government representatives from each country, is working with CEDARE to develop a regional strategy on groundwater.

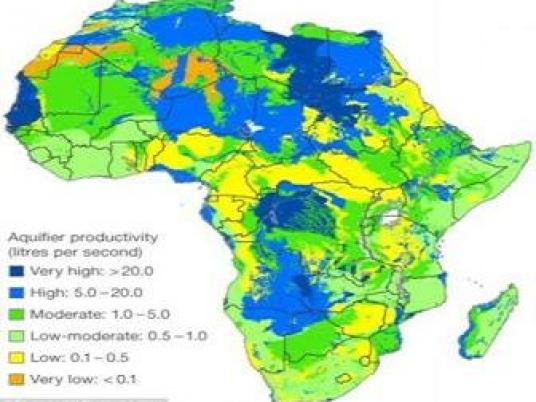

Last month, researchers from the British Geological Survey and University College London published an article in the journal Environmental Research Letters that mapped, for the first time, the aquifers across the continent and the amount they hold.

“The largest groundwater volumes are found in the large sedimentary aquifers in the North African countries Libya, Algeria, Egypt and Sudan,” the scientists said in their paper.

They estimate that reserves of groundwater across the continent are 100 times the amount found on its surface, or 0.66 million cubic kilometers.

But Stephen Foster, a groundwater expert at the Global Water Partnership who sat on the steering committee for the paper, said that groundwater is no cure-all for the continent’s water needs.

“Utilizing groundwater is more a question of investing and good planning than an absolute resource,” he said, adding that “small sources available at moderate depths, or small supplies in urban areas [should be considered] … but if you jump onto big demands of large-scale agriculture, it will requires both high-yielding wells and good replenishment, otherwise the storage won’t last many years.”

The study makes no claim toward the quality of the water available, and instead urges that the information be used as tool at a national and regional level to create “more realistic assessments of water security and water stress,” as well as to promote further quantitative research into the mapping of groundwater resources.

According to Foster, there needs to be better awareness among decision makers and development groups regarding the potential value of groundwater across the continent.

Abdel-Megeed agrees.

“Awareness is needed in some government offices, agriculture and investment sectors as well as housing sectors need to understand the limitations,” he said.