For 16 months, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has tried to convince us we are indebted to it for the revolution. In reality, it was the military council that was indebted to us for its newfound absolute powers.

Today, there’s enough debt to go around. The Salafis owe the revolution their historic political rise and escape from the noose of Hosni Mubarak’s state security. The country’s liberals owe the SCAF and the judiciary for the disqualification of ultraconservative Salafi Sheikh Hazem Salah Abu Ismail from the presidential roster. The military is indebted to the Muslim Brotherhood for its silent obedience throughout a year of violence against protesters and revolutionaries. The Brotherhood owes non-Islamist revolutionaries for kick-starting the uprising last year.

All of this debt has built up while the country is running in the red. Virtually no single political institution, party, organization, group, state apparatus or movement possesses a reservoir of absolute legitimacy in the current maelstrom.

Yet the one person whose debts are most colossal is newly minted President Mohamed Morsy. Many commentators and Morsy himself have admitted that even if he possessed executive power — which was recently stripped of him by the SCAF’s supplement to the Constitutional Declaration — the task of balancing the economy, uniting the public, managing the country’s increasingly entangled foreign policy, and most importantly enacting directives that fulfill the revolution’s goals of subsidies, dignity, freedom and social justice, appears at least insurmountable.

But even all of these challenges do not obfuscate his greatest burden. Like Atlas from the Greek myth, who was condemned to carry the celestial universe (depicted in art as the earth) on his shoulders for eternity, Morsy carries into his amputated presidential post a universe of un-payable debts.

Morsy’s greatest creditor is, of course, the Brotherhood, for nurturing him throughout much of his political and professional career and for pulling him out of near obscurity to lead its charge to the presidential palace. He owes Khairat al-Shater, the Brotherhood behemoth, for relinquishing the spotlight to him and entrusting him with this task. He cannot forget the organization’s investment of tens of millions of pounds, if not more, and the dedication of tens of thousands of its loyalists to energize his campaign.

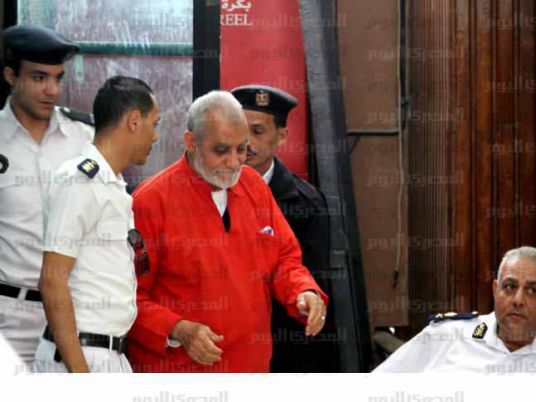

He owes Brotherhood Supreme Guide Mohamed Badie for exercising his authority and dominion to bestow his blessings, vet and allow him to be the face of a long-awaited Brotherhood presidency. That is why we should see Morsy’s public removal from the Brotherhood and the Freedom and Justice Party ahead of his ascendency to the presidency as a far-fetched and unconvincing gimmick.

A significant proportion of Morsy’s deficit is owed to the ruling military council, with which he’s been playing a game of rhetorical brinkmanship over the past few weeks. Both have flexed their muscles ahead of a seemingly conciliatory conclusion. Lest we be fooling ourselves, the Presidential Elections Commission, which in addition to being absolute and incontestable in its rulings, was appointed by the military council.

There are at least five scenarios the commission could have orchestrated to significantly disadvantage Morsy — including the disqualification of his former opponent, ex-Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq, which would have fielded an arguably more competitive contender — or barring Morsy from the race on the grounds of illegal campaigning by the Brotherhood and the FJP. But none of these things happened.

At Hike Step military base on Saturday afternoon, in what was dubbed a “transfer of power” ceremony, the SCAF reminded Morsy in not-so-subtle ways that had it not been for the generals, Egypt would not be where it is now, and by extension, neither would Morsy. So in the end, Morsy is president not simply because of the electoral win, but with a nod from the military council, a debt he will have to repay.

And if that wasn’t enough, perhaps Morsy’s greatest debt is to the electorate outside of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose support catapulted him past his contender. From revolutionary groups to individuals, from the April 6 Youth Movement to the ultras, from activist Wael Ghonim to the once-demonized Revolutionary Socialists, Morsy’s diametrically opposed camp is extremely wide and polarized, pushing him beyond his Brotherhood base.

Many of these groups “squeezed a lemon over themselves” (an adage meaning bit their tongues and acted against their natural will) and voted for Morsy to defeat the old regime. They did so despite the unflattering and often counter-revolutionary record of the Brotherhood throughout the transition. This non-Brotherhood electorate, which entrusted Morsy with its vote, expects to be vindicated in their support.

Asserting his revolutionary tendencies, Morsy participated in an electrifying mock swearing-in on a stage in Tahrir as if to spite the SCAF, then politely and obediently succumbed to its will the following day to get officially confirmed as president before the Supreme Constitutional Court. As the president becomes a more adept and charismatic performer with every engagement, he is also honing his ability to circumvent confrontation by speaking from both sides of his mouth. This ambivalence should force the revolution’s proponents to take heed and judge Morsy on his actions rather than his words.

Adel Iskandar is a media scholar and lecturer at Georgetown University.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.