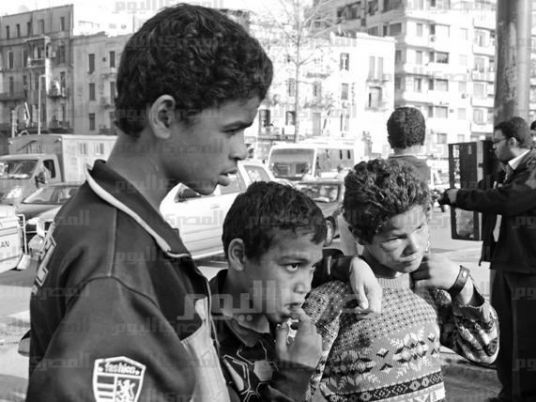

So many of the kids on the streets know exactly what you want to hear from them. They eye you up, suss you out and in minutes they conjure up the story you are there to hear. They have to be this clever. Their survival depends on it.

I remember speaking with one journalist who told me she was in awe at a child who told her she had joined the protests in January 2011 because she cared about the country and wanted to bring political and social change. I knew the girl she was speaking about well. She didn't give a crap about political change, simply because she didn't understand what the word meant.

I got to know the girls over many months — not formal 30-minute visits or interviews, but I'd really got to know them, by clapping while they danced, sympathizing when they spoke in group therapy, by laughing at stories of the street, by cleaning wounds after self-harm. It was because I lived those stories I felt I could ask Taghreed, one of the girls on the street, why the kids were really there in the squares.

So we took our interview roles: Taghreed happily holding the mp3 recorder in one hand turning it over and amazed that in a bit she would be able to hear her own thoughts (she had asked me to buy her an mp3 recorder so she could speak to herself in it because she wanted to keep a diary but couldn't read or write), and I took my interview position, holding her cheerful four-month baby who knew nothing but to smile all the time.

Many people to whom I tell the stories of the street girls comment that I must be strong to live and hear these stories. Every time I hear this I recall the ache in my heart at the smiles of the little babies — nothing pains me as much as the smiles. These little curves on the lips, the greatest manifestation of how equal we are, how painfully similar our starts are, how incredibly precious some smiles are to others because life is set out to break them, to give them nothing more to smile about.

And I hear Taghreed tell me about the revolution and the move the children who slept in Ramses Square made to Tahrir Square. She speaks of it as a migration, as if those little green, or what should be green, patches of land represent a city in their own right; a city with its children citizens, those kids without IDs, without shelter, without biological families and without protection.

Taghreed tells me that one child had come running to them in the great city of Ramses Square telling them that millions of people where in Tahrir. Two of her "married" friends (these are children who are 14, marriage and family makeup to street children are different to how we know them) decided it was best to join so they didn't miss the greatest opportunity to steal mobile phones. She tells me this and laughs for ages saying she wonders what the reaction of journalists would be to the real reason why some children were there.

But she goes on to say "not all the children were there to steal though! It was just so fun! For so long people were telling us that the street was bad, that we had to get off the street, but suddenly everyone was on it, everyone in the country was in Tahrir, so we moved there from Ramses. People there spoke to us, fed us, joked with us, some even tried to teach us to read and write. We even slept next to all these people with their good smells. And we helped them too. When food ran out we told them where the cheapest places to get food were. We taught them the best ways to run away from the police. That is because our favorite game is Atari."

When she saw a look of confusion on my face she explained: Police cars, we call them Atari, and we play all day running and hiding from them. But we all realized that the police in Tahrir were different, they didn’t waste time running after you, they just shot you instead."

Her stories and analysis of what led the children to the place where all the action was weren’t sinister. All the reasons, even stealing mobile phones, were understandable and I could relate to having started to know the kids. However, two years later, the children's answers to why they were taking part started the chills down my spine. The kids were speaking to my colleague Adel who had dedicated the last 18 years of his life working with the children. He looks down and tells me there’s been a change of tone, that he doesn’t know who’s been speaking to some of these children, but someone different has. The kids running around with Molotov bottles are asking him, “What worth does my life have? I want to die a martyr so that God could forgive me for all the bad things that I have done in this world. I want my death to mean something because my life didn’t mean anything. I want to die and have all those people in Tahrir talk about me, walk in my funeral. I want to die and have someone remember me, draw my face on the wall like all the others, so no, ‘baba’, I’m not afraid to die.”

The relation of the street children with the revolution has changed in the course of two years. However, it would still be a kind of romanticism to argue that children were at the front lines because they understood the meaning of revolt as a means to an end. The children, because they are children, are not to blame for the state of mind they are in when they take to the front lines.

What about 13-year-old Omar’s death? Omar, the little boy shot through the heart by the army that was meant to protect his borders against the enemy. Was he there to steal phones? No. Was he there because he wanted his little face etched in graffiti on the squares surrounding walls? No. Omar was shot because he was there. Omar was shot trying to earn an honest living off the streets that have become home to so many classes, religions, ages and ideologies. Omar was shot because he was in the way. But more than any other reason, Omar was shot because no one would be held accountable. Omar’s little heart took the bullet because some are too cowardly to hold those responsible accountable. This article is for all the Omars arrested and shot, just for being there because there was nowhere else safer for them to be.

Nelly Ali is a human geographer doing her PhD at Birkbeck College, University of London. She works with street girls and young street mothers in Cairo.