LUXOR — How do you capture, within the framework of a dramatic film, events that are as complex, multifaceted, and — most importantly — ongoing, as those constituting the chaotic aftermath of the recent revolution? The simple answer is: you don’t.

The past year and a half have seen many an Egyptian director, regardless of their level of experience, attempt to tackle the perfect-on-paper combination of film and the revolution, only to discover how hard it is to actually fit the two together. The few directors who have found success mostly did so by keeping their ambitions realistic, and their scope limited enough for their story to fit onscreen.

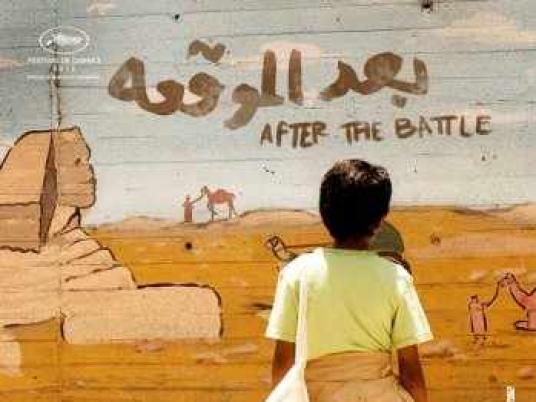

Yousry Nasrallah’s approach in “After the Battle,” on the other hand, consists of throwing everything he’s ever seen, known, and heard of the revolution at his audience, and then yelling at them. It’s a strategy that’s as simple as it is ineffective, and the results are even messier than it sounds.

Instead of presenting a tightly focused story with wider implications in the film screened at the first Luxor Egyptian and European Film Festival, Nasrallah does the exact opposite, unraveling a seemingly endless yarn that, even during its most interesting points, remains utterly inconsequential, not to mention entirely implausible.

Mahmoud (Bassem Samra) is one of the horsemen suffering the consequences of his involvement in a regime-sponsored attack on Tahrir Square’s pro-democracy protesters; a real-life incident now referred to as the “Battle of the Camel.” His relatives worry that he’s jinxed, NGO workers refuse to share with him the horse fodder distributed to other horsemen, and his kids get bullied at school.

Enter Reem (Menna Shalaby) a young, attractive (we’re told) NGO worker who may or may not be insane, but almost definitely is. Reem joins her friend in volunteering to distribute fodder to the horsemen, despite the fact that the whole way there she repeatedly refers to the horsemen as “thugs” and “criminals,” implying that they shouldn’t be helped, and jumping at any loud sound other than that of her own ranting. When she witnesses Mahmoud being denied both fodder and the opportunity to perform with his dancing horse, Jamaica, she has a sudden change of heart, and the two head behind the stables and make out. But then she finds out he’s married, at which point audience members scratch their heads in confusion and wonder what it is they just walked into.

It’s hard to complain about poor characterization and dubious plotting when clearly, crafting a strong story isn’t the filmmakers’ priority. Nasrallah and writer Omar Shama use plot points as mere pegs for their long list of post-revolution concerns, complaints, and debates, never settling on any issue long enough to give it its proper due, and, worse yet, never committing to a single, sound voice. Which is not to say all films need to carry a clear message, or that a revolution-themed film must either praise or condemn recent history. But — besides begging the question of why the filmmakers even bothered with hobbling together such a weak story when they clearly wanted to make a documentary — the absence of any type of underlying commentary, and the need to present all sides of all arguments leave the film with two fundamental problems.

The first is that it makes the characters seem crazy. The filmmakers aren’t as attached to Mahmoud as they are to the idea of having a horseman in their film; the same goes for Shalaby’s shrill good-intentioned, yet ultimately clueless, “liberal.” By reducing their characters to mere symbols of social disparity, the filmmakers lose a grip on who these people are as individuals. As a result, Mahmoud is all possible incarnations of the Battle of the Camel offender — the victim of a conspiracy, the desperate family man, the hired thug, the resentful oppressed, to name a few — despite the increasing contradictions this leads to in his behavior.

It is Reem’s character that suffers the most, though: from swooning over Mahmoud, to her genuine attempts at convincing his abused wife to take the kids and run; telling Mahmoud’s family at various points to stay out of her life, and then showing up at their children’s school to protect them from bullies. She jumps from scene to scene, getting involved in everyone’s business and generally pissing people off by trying to resolve situations in ways that are bound to end in disaster. None of it makes any sense, and the fact that she’s shown to be in the middle of a protracted, supposedly symbolic, divorce process with a man she claims she can’t stand but still keeps one of his shirts, only pushes the impression that this woman is crazy, and this is a film about how the revolution (or divorce) made a woman go crazy.

The sense of schizophrenia extends to the film’s backdrop as well, particularly in Mahmoud’s case, who, when it’s convenient to the storyline, is treated like a pariah, only to be found in other scenes laughing and getting high with friends who are giving him a good ribbing over the whole ordeal. More upsettingly, the characters — or rather the filmmakers — can’t seem to pinpoint whether they disapprove of Mahmoud’s participation in the battle, or the fact that he was knocked down, beaten, and “humiliated” by protesters.

The second, bigger, problem is that, by exposing only the surface of all arguments and never providing any insight or commentary of their own, the filmmakers reduce these otherwise valid viewpoints to mere blips on a radar, and not very strong ones, either. Opinions are condensed into familiar soundbites, and the supporting players are such stereotypes you can almost see the labels floating over their heads. Large portions of the film play out like a yelling match between particularly naive NGO workers, while others segments consist of clearly unscripted complaint sessions filmed in actual slums.

But for all its blabbering, the film only reiterates everything that’s already been said about the revolution, without adding anything of its own. Not only does Nasrallah not contribute, he detracts from the general discourse by ripping all those debates out of their original context, and dumping them in his film in the hopes that they’ll give it something to say. It’s a cynical move, despite the fact that the film is far too gutless to be so itself, and its relentless showcasing of multiple perspectives mostly reeks of pandering, and indecisiveness. In that sense, “After the Battle” offends by being a cowardly work hiding behind a few overheard “bold” statements, and a lot of shouting.