“This is either gonna be wildly successful or a complete disaster,” Austin Tice wrote in May 2012, on the eve of a dangerous journey to bear witness to history. “Here goes nothing.”

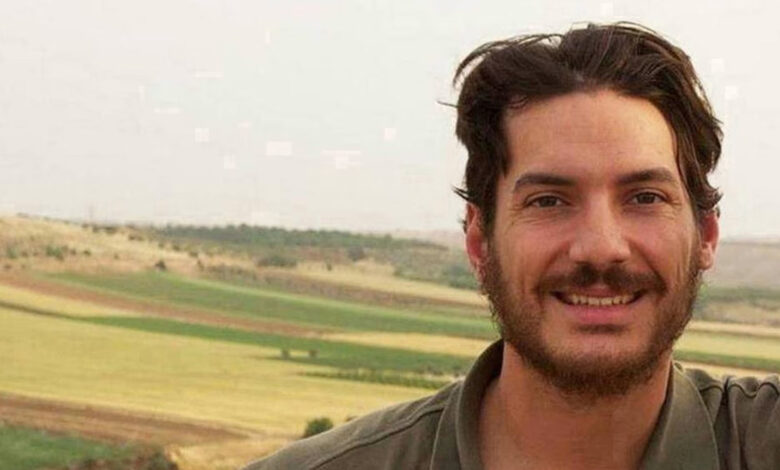

Tice, a physically towering former Marine and fledgling journalist, threw himself with grit and resolve into war zones, friendships and the injustices he cared deeply about.

But he is yet to return from that journey. Tice disappeared in Syria two months after setting off to cover the country’s crippling civil war, sparking a 13-year mystery that has tortured his Texan family and plagued Washington’s relationship with Syria’s brutal former dictator, Bashar al-Assad.

For more than a decade, nobody has seen or heard from Tice. His family has never lost hope that he is alive, even as successive administrations – from President Obama to President Trump – failed to bring him home.

But in December, Assad’s repressive regime – which had always denied capturing or killing Tice – collapsed in an instant. And in the chaotic months since, clues about Tice’s fate have begun to seep through the walls of Syria’s once-impenetrable prisons and palaces.

Now, a CNN investigation has revealed a remarkable development. Bassam al Hassan, a four-star general close to Assad, told CNN’s chief international correspondent Clarissa Ward that Tice was killed in 2013, the year after his capture. The order came from Assad, he said. But Hassan failed an FBI polygraph test, CNN has confirmed, and it is unclear which parts of his story remain a lie.

“Austin is like a bridge between America and Syria,” Waseem Enawi, a Syrian activist who hosted Tice in his home in Yabrud for three weeks, told CNN. “Through what happened to Austin, people can understand what happened to hundreds of thousands of Syrians,” he added.

“It’s the only good thing I can think of to come out of all of this.”

Long before his journey to Syria, Tice knew he wanted to make an impact.

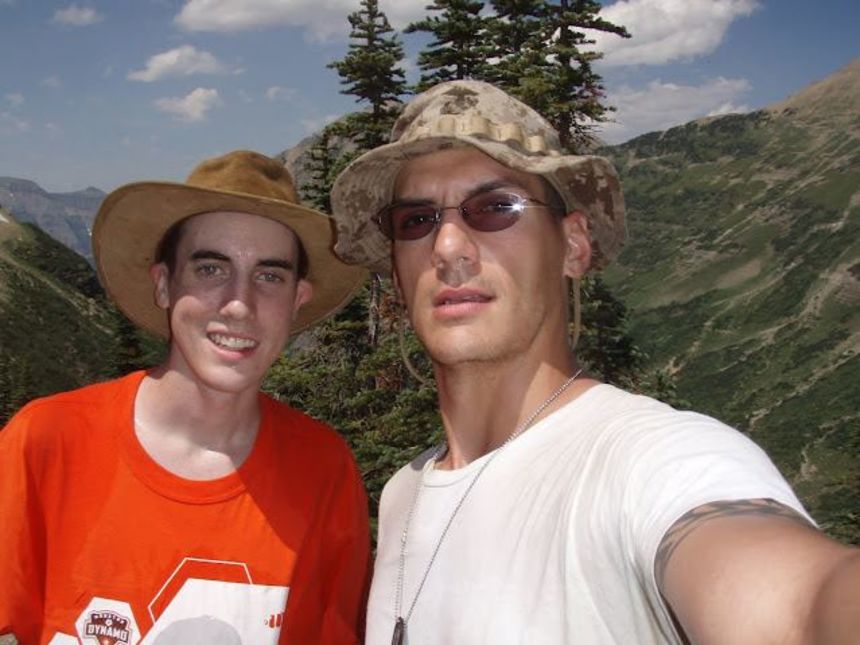

The oldest of seven siblings, Tice was home-schooled by his devoted Catholic parents, Debra and Mark Tice, in Houston. The family loved to travel; they would visit Mexico at least one a year, took several cross-country road trips, and spent three months in Europe while Austin was a teenager.

“It was really important for my parents that we knew that there was a whole world out there,” Abigail Tice, Austin’s youngest sister, told CNN.

Tice was fiercly protective, Abigail remembered. “Whenever I would have a high school crush, he would talk to them and (say): ‘That’s my little sister, you better treat her with respect.’”

When Abigail’s daughter was born, Austin became a “huge, loving teddy bear,” Abigail told CNN. “Every single moment that he could, he was playing with her.”

At 23, Tice joined the Marines. “I think he saw the Marines as the greatest challenge,” said Brian Bruggeman, Austin’s battalion commander during his deployment to Afghanistan in 2011. “Austin was attracted to the way the Marines lead.”

Tice stood out, Bruggeman told CNN. “He was gregarious and extremely curious.”

He worked to assimilate his Afghan interpreter into the battalion, Bruggeman recalled, telling the local translator: “You’re part of our unit now.” A year later, Tice was delighted when the interpreter was accepted to an American college, and the man stayed with Tice’s family in Texas after moving to the US.

In Afghanistan, Tice opened up to his peers. “He let me in,” Bruggeman said. “He loved to talk about his family,” his commander recalled. “I felt like I knew his mom well before I ever met or talked to (her).”

Tice had “an epiphany” while in Afghanistan, Bruggeman added: He wanted to get into photojournalism. He celebrated his 30th birthday by buying a camera and began documenting his deployment, sharing his stream of consciousness on blogs and on Twitter.

But Tice’s time in Afghanistan changed him in darker ways, too. He saw several fellow Marines killed or injured: One lost his left leg when an improvised explosive device (IED) detonated, and another was fatally electrocuted when his radio antenna touched a power line. He developed a morbid sense of humor about his own vulnerability.

“Heading out soon on a horribly conceived mission,” he wrote in one tweet. “Hopefully (it) will be forgotten like most dumb missions are; otherwise, see you on CNN.”

“I’ve served on the front lines of both our wars,” he wrote at another point, referring also to his service in Iraq. “Aside from my men, I have yet to see anything worth dying for.”

Tice returned to the US to complete a law degree at Georgetown University as the Arab Spring toppled autocrats and upended decades of tight-fisted rule in the Middle East. “Time to work hard, be dull, and prepare for the next great adventure,” he wrote.

But becoming a lawyer wasn’t his calling, and being dull wasn’t his nature.

“It’s not the path I saw for him,” a family friend of the Tices told CNN. “He was too much a person of action to sit behind a desk.”

So, after his second year of law school, Tice set his eyes on a new mission. And he wanted his brother to join him.

“I slipped into an empty room at the little house we were renting and listened, astonished, as he told me he was planning a trip to Syria that summer of 2012,” Jacob Tice wrote in a 2020 opinion piece for CNN.

Jacob turned him down because he couldn’t imagine traveling to an active war zone. But he wrote: “I encouraged him to follow his heart and to bear witness to the escalating conflict in Syria. I believed in his vision, admired his grit and was behind him completely.”

Tice understood the risks. He had a long-running streak with a close colleague in the online game Words With Friends, and he made a deal: If I don’t play my turn for more than a week, let people know I’m in trouble.

The night before he left for Syria, Tice met his family friend in a DC bar. “There was no talking him out of this,” the friend told CNN. “He wanted to tell their story. Because he felt like nobody else was there.”

“I think about that evening all the time,” added Tice’s friend, who asked not to be identified. “If I could have, if I could have stopped him.”

“God damn it, I wish I’d said the right thing.”

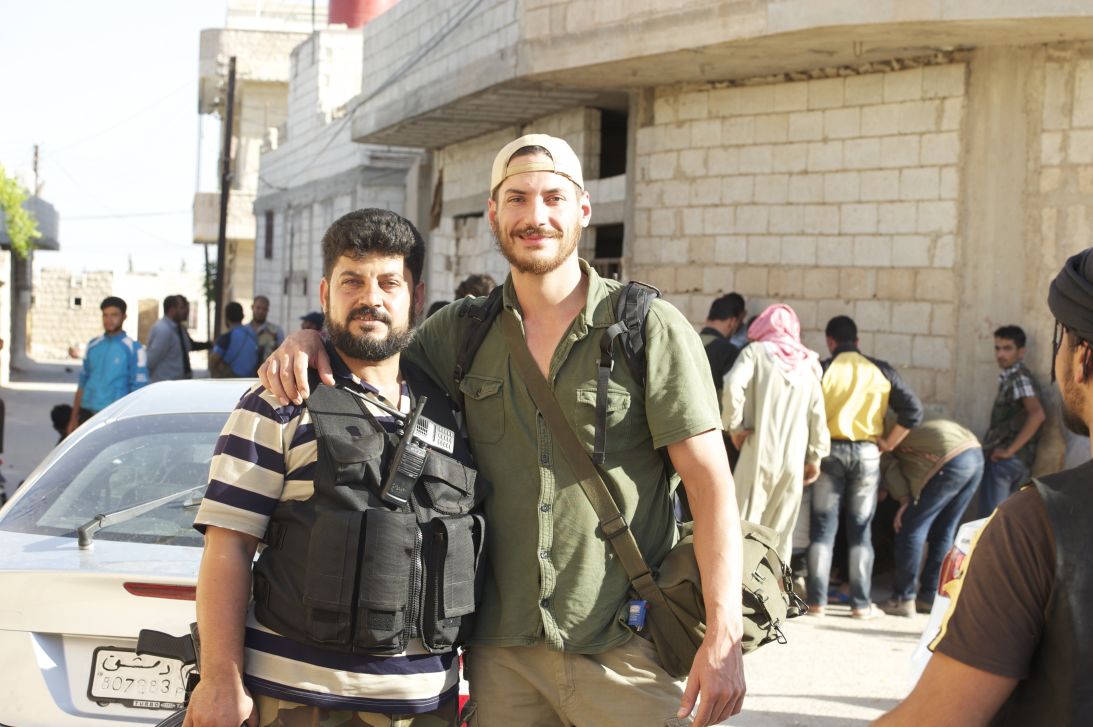

At the time of Tice’s trip to Syria, the country was seized by a violent civil war. The Free Syrian Army (FSA), a coalition of rebel fighters, was advancing towards the capital Damascus in the country’s southwest and towards Aleppo in the northwest. Both cities had become key fronts in the conflict after Assad’s forces began cracking down on peaceful protesters the previous year.

Tice stayed with Enawi near the country’s northern border for nearly three weeks, interviewing locals about the war. “Everyone (was) saying hello to him – he was a little bit famous,” Enawi told CNN.

Tice wasn’t a reporter yet, but he didn’t want to waste time. “He desperately wanted to be a journalist. He wanted to be a success,” Liz Sly, a Beirut bureau editor at the Washington Post who worked with Tice and published three of his stories, told CNN. He wanted to learn by doing – and he was good at it.

“Lots of people struggle to write a news story. They don’t get it,” Sly said. “He didn’t seem to struggle at all. He seemed a natural.”

But Tice was raw, and a growing cast of seasoned journalists worked to hone his restless energy. David Enders, who traveled with Tice through Syria for several weeks and worked with him on a series of stories for McClatchy, told CNN: “One of the first things I said to him was, ‘if you tweet our location in real time, you will never see me again.’”

Tice and Enders embedded with a rebel unit and raced towards Damascus, sleeping in safehouses with their boots on and carrying only what they could run with. They jumped on makeshift buses and on the back of motorbikes and sometimes walked, evading government shelling and helicopters as they went.

“I am embedded w #FSA. Newsworthy stuff going on daily,” Tice tweeted in late May. “If someone wanted to hire me that would be great. Student loans don’t pay themselves.”

On one occasion, a tank shell hit the front of a house the pair were taking cover behind, Enders said. “I don’t have any recollection of (the) sound,” he said. “I remember the impact, and hitting the ground.”

It was more violent action than Tice had seen in the military, according to Enders. But the pair bonded over their profession and their recent divorces, and Tice would often share stories about his family. Once he interrupted a conversation among rebel fighters to tell them their plan to ambush a government convoy wasn’t well-planned enough.

Tice would subsequently win the George Polk Award for War Reporting, alongside Enders. But the pair eventually parted ways. Rebel forces were gaining control of the suburbs surrounding Damascus, the scene of violent fighting, and Tice wanted to get there in time to see the Assad regime collapse.

“It was extremely, extremely difficult and dangerous – the government was cutting off supply lines and transit routes,” Enders said. At one point he broke free of a rebel safehouse and started walking towards the city, until the rebel fighters retrieved him and locked him in a room for his own safety.

Tice called Sly to vent his frustration. “He was so convinced Assad was going to fall,” she said. “And he had to be there for it.”

That August, Tice turned 31. “Listening to the shells usher in my birthday,” he wrote on Twitter. He was in a reflective mood. “Afghanistan, California, DC, Egypt, Turkey, Syria. What an insane year.”

The year ended with Tice unwinding at a pool party with FSA rebels, according to a post from him in the early hours of August 12. Taylor Swift’s music blared in the background; Tice was an unabashed Swift fan. “Hands down, best birthday ever,” he wrote.

That was the last tweet he’d send. In Beirut, Sly heard from an editor at the Post, where Tice had filed a fourth dispatch. “Austin hasn’t answered his questions,” the editor told Sly. “He always does. Have you heard from him?”

It took a few days for concern to set in. Tice had been planning some R&R, and perhaps he was on his way to Lebanon or Turkey to take a break.

But as the days passed, it became clear that Tice had been captured. Sly, Enders and the other journalists Tice had befriended during his rapid professional rise frantically reached out to their contacts, but nobody knew what had happened to him.

Back home, the Tices were on a family vacation in Gulf Shores, Alabama. Austin had been in contact throughout his time in Syria – he knew his siblings and his parents were worried about him – so it didn’t take long for something to feel off.

“It’s one of those moments in our family’s history where there’s a before and there’s an after,” Abigail told CNN.

They cut the trip short, and over the ensuing weeks, the phone on their wall in Houston never stopped ringing. Media members quickly converged outside their house. It was overwhelming, Abigail said.

Both Sly and Enders had nightmares about their colleague. “There was one where he was in a forest, and people were shooting at him, and I had to warn him,” Sly remembered.

Then, in September, a video appeared on YouTube. The shaky footage showed Tice, blindfolded, weeks after his disappearance. He recited a garbled prayer in Arabic, then added, in English: “Oh Jesus, oh Jesus.” The video apparently showed him surrounded by jihadi militants, but the US quickly reached the conclusion that it had been staged by forces loyal to Assad.

Marc Tice, Austin’s father, said in a statement at the time that seeing the video was “difficult,” but “knowing Austin is alive and well is comforting to our family.”

No footage of Tice has been seen since, but the family never lost that hope.

“We know he’s alive and we know that eventually he will be home and our family will be together again,” Abigail said. “We’ve never doubted it once.”

Austin’s disappearance transformed his mother, Debra, into a geopolitical crusader overnight. She has met with successive US Presidents and told CNN earlier this year that President Trump’s team started reaching out to her soon after his election victory last November, describing their work on the case as “fantastic.”

As time has worn on, his mother’s resolve has only grown. “Debra Tice is a force of nature,” the longtime family friend told CNN. “This woman’s singular focus in life is amazing, and it’s inspiring.”

Then, in December, came renewed hope. Assad’s regime dramatically and decisively fell to rebel fighters, twelve years after Austin Tice believed it would. In the days that followed, Debra wrote a letter to several leaders – including Russian President Vladimir Putin – who gave the fallen despot sanctuary after he fled Syria.

Her letter elicited a public response from Putin, who said at his end-of-year press conference that he would talk to Assad about Tice’s whereabouts.

“I’ve never seen somebody with the guts to stand up to any world leader, to anyone, to say the things that she has said to people to try and get her son out,” the Tices’ family friend said.

Thirteen years after he vanished, Austin Tice’s fate may never truly be known. His disappearance still haunts those who knew him. It changed Sly’s approach to hiring freelancers — “You can’t just take people (who) bound into the country with no background or experience,” she told CNN. She also asks herself: “Could we have done more?”

But Tice knew he was dancing with danger, and those close to him all acknowledge one thing: Once he set his heart on something, trying to change his mind was impossible.

“Every person in this country fighting for their freedom wakes up every day and goes to sleep every night with the knowledge that death could visit them at any moment. They accept that reality as the price of freedom,” Tice wrote on Facebook less than three weeks before his disappearance.

“No, I don’t have a death wish – I have a life wish,” he continued. “Coming here to Syria is the greatest thing I’ve ever done, and it’s the greatest feeling of my life.”

Clarissa Ward, CNN’s chief international correspondent, contributed to this story.