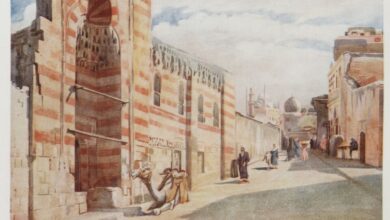

The 1889 Paris World Exhibition included an Egyptian exhibit built by the French to represent a street of medieval Cairo. Meticulously constructed houses and a mosque were arranged on the street in the haphazard manner of a bazaar. Frenchmen dressed up as “Orientals” and sold perfumes, pastries and tarboushes, while fifty Egyptian donkeys–along with their drivers–were imported from Cairo to carry people up and down the street. Inside the mosque, visitors were met with a coffee shop in which belly dancers performed and dervishes whirled.

Sarah Rifky, curator of the Townhouse Gallery for Contemporary Art, cited this anecdote from Timothy Mitchell’s 1988 book, Colonizing Egypt, at The Practice of Orienteering panel discussion held one night before the opening of the 12th International Cairo Biennale to discuss the curatorial vision of Orienteering, the American exhibition at the biennale. Ridiculous as it may seem, the story demonstrates the role Orientalism–scholarly knowledge of Eastern languages and cultures–has had in shaping perceptions of the Middle East and the anxieties people from the region have regarding exhibitions that deal with the “Orient.”

Orienteering showcases the works of four female Arab-American artists: Annabel Daou, Dahlia Elsayed, Nadia Ayari and Rheim Alkadhi. Adapting the title from a 19th century Swedish military training technique, by which soldiers were asked to locate “control points” in unfamiliar territory before returning to their bases, and playing on the phonetic resonance of “Orienteering” with the “Orient,” exhibition curator Ranya Husami sought to critique reductive interpretative frameworks of artwork from the Middle East and its diasporas. The artists were asked to operate like “Orienteers,” creatively addressing control points, such as geographic specificity and cultural hybrids through their work.

Intending to depart from the well-trodden theoretical terrain of Orientalism, Orienteering’s success was only partial. The exhibition was framed from the beginning as an overt attempt at cultural diplomacy highlighting the Arab-American experience and its relevance to Cairo. At the panel discussion, a representative of the US State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs lauded its selection of the Arab-American National Museum–an ethnic museum inaugurated in 2005 in Michigan to promote Arab-American cultural heritage–to represent the US at the 2010 Cairo Biennale as a successful example of intercultural dialogue.

The September 2001 terrorist attacks in the US triggered great interest in art from the Middle East and the Muslim world. Prices for artwork from the region and its diasporas skyrocketed on international auctions. A plethora of exhibitions referencing the Middle East have been curated and numerous joint projects between East and West were organized to bridge existing tensions. The Danish have taken the lead in this regard since the 2005 cartoon incident.

Artists of Middle Eastern descent have been continuously pigeonholed as cultural ambassadors. Nevertheless, many have succeeded in critiquing such frameworks through their artwork, such as Egyptian artist Wael Shawky, who has been using cliche imagery of the Middle East–desert landscapes and Bedouins–in his Telematch Series to question dominant historical narratives of the region. “It is easier for artists to decline invitations to participate in such shows. The real challenge is to engage with them and deconstruct the frameworks they impose onto artists,” explains Alkahdi. “It all comes down to the artwork’s ability to encourage the audience to go beyond simplistic propositions.”

Daou’s work, From where to where, uses a linguistic pun–the title idiomatically translates in the Lebanese dialect of Arabic as “how dare you?”– to question time and space as constituents of identity. Adopting a journalistic style, Daou asked random strangers in Beirut and New York three questions: “Where are you now? Where are you coming from? Where are you going?”

The responses were developed into a sound piece, which accompanied her single answer to all three questions, “I am here,” repeatedly transcribed onto a withering paper map. Symbolizing fragility, the map is meant to negate the myth of violence as a generator of artistic production in the Middle East.

Attempting to demonstrate her liberation from spatio-temporal constructions of identity, Daou’s translation of the verbal responses into visual language was, nevertheless, didactic. The juxtaposition of responses she received at Beirut and New York, where the former emphasized ethnic and political inclinations of their hometowns and the latter simply cited the physical places they came from–like the bus station or park–is unsuccessful in reorienting audiences to reflect on a complex history in Lebanon that informs people’s sense of identity.

Elsayed creates an autobiographical map of her numerous travels with her family in search of a new home due to ongoing political strife. Her maps reflect the social and emotional experiences of the cities she lived in rather than their physical architecture. Random textual inserts–such as “Caught Up In, Tangled” and “The Dogged Pursuit”–emphasize notions of displacement related to the Arab-American experience. Again, the translation of her emotional states is literal, preventing the audience from engaging with the topic in meaningful ways.

Ayari’s paintings are more visually interesting. The artist uses surrealist imagery to hint at attempts at co-existence and integration. In Camo, Wild Flowers, two imaginary creatures hide from an omnipresent eye in a field of impasto candy colored wild flowers. Blue Domes further plays on the idea of camouflage. A blue dome is used as a basic motif that loses its identifiable characteristics through repetition.

Alkahdi’s two-part work, Domestic Floor Covering and Conference of Flies, is by far the most interesting piece in the exhibition. The absurdist work offers the audience a visual representation of traumatic experiences of displacement brought about by war. Alkahdi contrasts a precious domestic object–an oriental carpet that belonged to her grandmother–with a wall installation of flies, a domestic nuisance. Based on official statistics about the Iraqi war since 2003, al-Kahdi cut out circular holes in the carpet creating a visual and intimate map of often overlooked aggregate numbers. The decaying carpet surrounded by flies alludes to a desert landscape and plays on perceptions of value and time to emphasize the marginalization of displaced communities globally versus their hyper visibility in their new host countries and the difficulties associated with integration.

It remains difficult to separate the artwork from the overarching framework of “Orienteering,” as the exhibition magnifies the artists’ Arab-American identity. Nevertheless, the heated debate around the show helped audience members reflect on their existing prejudices rather than dismiss them all together. It also enticed some of the artists to reflect more critically on their own artistic practices, as acknowledged by Alkahdi.

Orienteering is showing at the Palace of the Arts at the Opera House grounds in Zamalek as part of the 12th International Cairo Biennale. The exhibition is open Saturdays through Thursdays from 10 AM to 2 PM and from 5 PM to 10 PM until 12 February, 2011.