Hassan Khan’s film “Blind Ambition” reminds me of high drama, westerns, myths, operas. But it’s only 46 minutes long and consists mostly of close-ups of actors out and about in Cairo, spouting lifelike dialogue, shot in a shaky handheld style. There’s no music, hero, love story, weapons, or plot.

There is a momentous silence. There is traffic. Often both at the same time, so the traffic feels historic. There are nine situations, involving nine different sets of characters. They could be everyday encounters, and they are largely tense, disappointing. Inside each encounter, but more conspicuously separating each of them, is the silence and the traffic.

The film is gripping because there is a strange compelling mixture of uncannily real and very artificial. It is set in Cairo, but there is no noise apart from the characters speaking to each other. Something natural — very convincing, sometimes semi-improvised dialogue — has been lifted up, out of the film, and crafted — recorded in a dubbing studio – before being placed back, like a hyperrealist element in an otherwise naturalistic painting.

In a boys’ football game on an unnaturally small informal pitch, their re-made shouts become calm and selected — sporadic noises like in a video game, where a certain action rewards you with a certain sound effect.

The film is also edited to give a barely convincing illusion of real time. The style depends on the nature of the encounter: when the camera follows two young women as they walk down a shopping street arguing, frames have been taken out to speed up the visuals, matching the women’s overlapping retorts. In an upmarket café four colleagues talk, but the camera only sees one at a time: they are isolated, might not even be in the same room.

Each segment can be seen as some sort of power struggle — people positioning themselves in relation to one another. Obsequiousness, threats, patronizing offers of help, people trying it on, lies. Money keeps cropping up in conversation (“let’s buy something,” one of the young women keeps saying) and class differences are evident in the relationships and language. (It’s interesting to see that highlighted now, as a reconsideration of the way class manifests itself in Egypt would be truly revolutionary.)

Another reason the film is gripping is the details, the meticulous specificity of the dialogue, clothes, and locations. It feels like Khan knows loads of people. He is capable of observing, absorbing details and then projecting them with extreme realness and fantasy. Each character is a symbol, yet super lifelike. Most exceptionally, although the camera focuses on them, the characters are not elevated from the crowd or their environment. We are inside the city.

Khan shot his black and white “low-fi epic” using a Samsung phone in 2012. He has no particular interest in mobile phone cinema – “this work made sense to me made this way,” he says. He auditioned more than 100 actors, and chose 27 to appear in the film. He did all the shooting himself except for the transitional scenes which involve entering and exiting some mode of transport, with each actual journey with its patient passengers brutally reduced into a few flashing images. He did all the editing, a skill he has largely taught himself.

In the last encounter, the camera follows a suited man as he walks, the keys swinging from his fingers at the center of the image, and past them the ground. Eventually he comes out above the city, in a café on top of a skyscraper overlooking Ramses Station.

Khan made a short video with the same title in 2005, but shelved it after showing it once. Also with the title is an object used in an installation and a book called “The Agreement” (2011). In the book, very short stories set in Egypt accompany some small objects he commissioned here. Khan says “The Agreement” and “Blind Ambition” are linked through the fact that they are both “detecting a social reality, using it as a material, and transforming it into a suspended state.” In “The Agreement,” he says, this manifested itself in the literary style of the text, and the enigmatic quality of the objects. In “Blind Ambition,” it is in the film’s formal conditions – the silence, its “super constructed” nature. By coincidence, he says, two men from a story in a coffee shop in the book also appear in the film.

The work is being premiered in Egypt tonight, as part of D-CAF. Khan hasn’t exhibited his artwork much (although he regularly shows works in screenings, performs concerts, and participates in public conversations) in Egypt over the past several years because he doesn’t want to compromise the way in which it is shown – the necessary resources are scarce here – but he is now working on the idea of bringing his huge selected survey exhibition shown at SALT, Istanbul, last year, to Egypt. Hopefully for 2014.

People in Egypt will presumably get things in the film that its previous audiences didn’t. They might also be more likely to draw parallels between “Blind Ambition” and the work of Khan’s father, the filmmaker Mohamed Khan, with its atypical heroes and celebration of mundane detail.

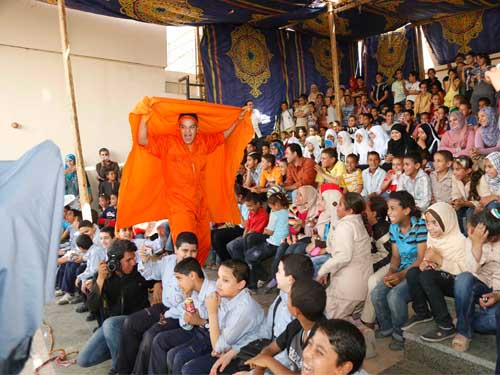

One reason D-CAF seemed like a good context in which to premiere the film in Egypt is because it aims to give certain elements of contemporary art mainstream exposure without compromise, Khan says, and “We need to have conversation.” He compared the current situation in Egypt, with its potential for dialogue, to when he started out showing work in the mid-nineties and you had to spend a great deal of energy setting up situations where the public could see your work, in which you were going to be blasted anyway.

Khan also chose to premiere “Blind Ambition” in Egypt as a stand-alone thing rather than within a curatorial framework. After this he doesn’t mind so much where it’s shown. He is happy that the screening will take place at the Radio Cinema, one of Cairo’s old big cinemas which is normally closed, as he went there to watch films as a kid.

Right from the title sequence – old-fashioned big white letters on a black screen – the movie feels like auteur cinema. The combination of real and fake, or spontaneous and constructed, seem to come out of a sideways approach to film as a medium to be taken apart, its parts held up and examined. “It breaks certain film conventions, although not for the sake of it,” he says.

The film shares the uningratiating quality of all of Khan’s works, but it is one of the enjoyable ones. It is enjoyable even when things are moving too fast to understand, because the film is impressively precise and uncompromising.

“Blind Ambition,” in Arabic with English subtitles, will be screened on Sunday at the Radio Cinema at 7pm. The screening will be followed by a conversation and a Q&A session with the audience both moderated by the writer Ahmed Naje.