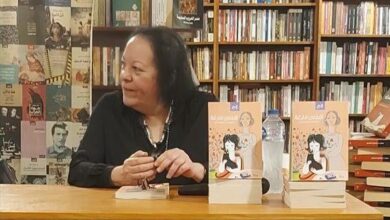

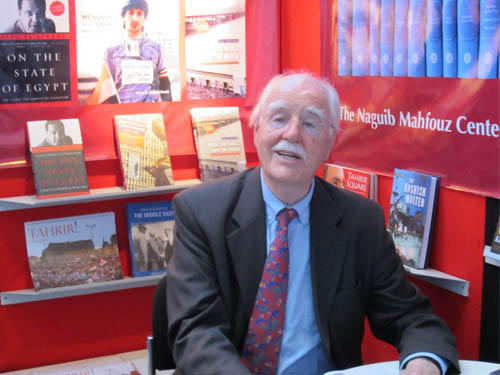

At the 2010 Naguib Mahfouz Medal ceremony, AUC Press Director Mark Linz produced a freshly printed copy of Amina Zaydan’s "Red Wine" (AUC Press, 2010). Zaydan’s book, which won the medal back in 2007, was initially scheduled for English-language publication in 2008.

But the translated “Red Wine”—Zaydan’s second book—just became available this month.

Unfortunately, extra production time has not meant a smooth English version of this compelling and complex novel. The translation, from Sally Gomaa, has many strangely turned-out sentences, which mimic the Arabic but fail to clearly express the essence of the prose.

The awkward wording is particularly noticeable in the novel’s opening section, or “overture,” when the reader is plunged into a complicated timeline: the Suez conflict, the death of the narrator’s mother years later, the narrator’s failed marriage.

Here, children play inside the bombed-out buildings of Suez. To entertain themselves, they guess at which building will be hit next: "Most of the prizes that consisted of candy and whistles went to Asaad, whose predictions usually came true as he led us through the hard-hit homes and reminded us of how they were as of yesterday, an arrogant boy who cared nothing for Abdel Halim’s love songs, grinning stupidly as I poured them into his ears to carry back to Andrea."

The going here is a bit rough, but it’s worth digging out the book’s three main characters: Suzy (the narrator), Andrea (her first love, of Greek descent) and Asaad (perhaps a betrayer, perhaps also beloved). Our perception of these characters changes a great deal over the course of the book, which Mahfouz-medal judge Fakhri Saleh called “the novel of disillusionment par excellence.” One might also call it the novel of betrayal.

If a reader passes through the overture and makes her way into the first act, the English prose becomes more easy-going. The landscape also grows clearer: Suzy Muhammad Galal—like Andrea and Asaad—was born in Suez and comes of age during the conflict years of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The book ranges over the four decades of Suzy’s life, focusing mostly on her failed marriage, her problematic relationships with her parents, and her failure to become a “hero.”

The book shares common traits with Mekkawi Said’s “Arabic Booker”-shortlisted “Cairo Swan Song,” also published in 2007. In both books, promising Egyptian protagonists are sucked into worlds of drinking and drugging. Both protagonists have reason to consider themselves failures. But “Red Wine” is much more nuanced than “Cairo Swan Song”; even its minor characters are fully dimensional, and echoes between Egyptian history and the characters’ lives enhance our understanding of both.

Suzy is unable to sort out her romantic, social or family lives, and tries to save herself through scholarly work. For much of the book, she intends to write a PhD dissertation on “The Resistance Hero in Egyptian and Greek Literature: A Comparative Study,” a clear tribute to her first Greek-Egyptian love. However, at the book’s end, she changes this to “Judas in Egyptian and Greek Literature.”

Judas, in this context, is not necessarily evil. In its final pages, the book spends a great deal of energy wondering if we have misunderstood Judas. It asks if Judas was perhaps put up to the task by Jesus:

"Judas is now innocent according to the Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art in Switzerland, which published a manuscript, dating back to 300 AD, in which Jesus tells Judas that among his followers “he will exceed all others” by sacrificing “the man that clothes me,” referring to the human form that clothed the divine spirit."

In a way, the scrolls—which were found in the 1970s and first publicized widely in 2006—seem dropped in unnaturally at the book’s end. Suzy has evinced no previous interest in theology or in ancient history, and the scrolls feel more like a writerly solution than something that has grown organically from the story.

The book’s finale also arrives a little too neatly wrapped. Still, what’s really keeping “Red Wine” from fully living up to the anticipation is the awkward translation. Nevertheless, it is a strong and heady read.