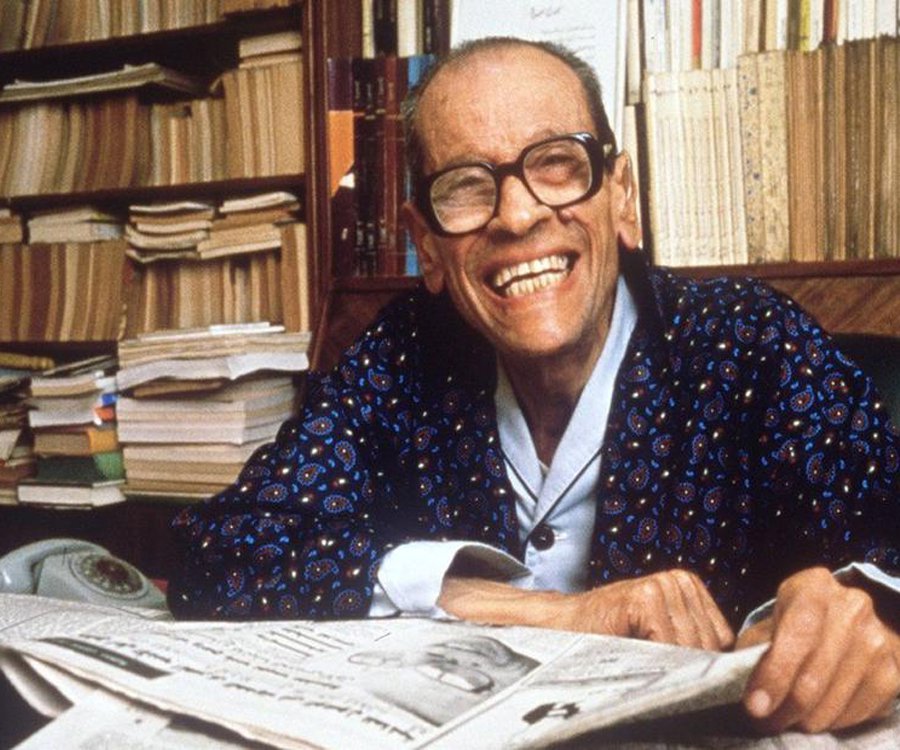

Surrounded by piles of books shelved on wooden compartments, hardly ten people gathered in the cultural salon hosted by Alef bookstore last week. The slim crowd sat to listen to a young satirist who has just released a book mocking political and social realities in Egypt.

Alef is one of the youngest bookstore chains to open in Cairo, raising the number of American-style book outlets to nearly 30 in less than a decade. In recent years, the book market has witnessed a relative boom in bookstores that seem inspired by the “Barnes and Noble” model with their neat interior design, expensive gift and stationary shops and their up-to-speed customer services and marketing departments.

“These bookstores came to fill in a genuine vacuum and we still need more and more of them,” said Emad Aladly, the media spokesperson of Alef.

Alef opened its first branch in Heliopolis last summer. Like some of its competitors, it branched out with six new stores in less than a year–an expansion that raises questions about the prospects of the book business in a country where a massive 90 percent of households do not read books, according to official statistics.

“People think bookstores have become more or less like juice shops or grocery stores,” said Karam Youssef, the owner of Kotobkhan in Maadi, with a sarcastic tone. “You find more than one bookstore in the same neighborhood and they all tend to kill each other.”

Kotobkhan had no competitor when it first opened in 2006; it was the only bookstore providing thousands of Arabic and foreign titles to the Maadi community. Besides books, the store has also hosted film screenings, book discussions and public lectures.

This year, Youssef must have felt pressure after Diwan,another popular retail chain,opened a few miles away from her outlet. To make the challenge fiercer, Alef is expected to step into Maadi in a couple of months.

“The question is can the market take this number of bookstores?” wondered Youssef.

Hind Wassef, the co-founder of Diwan bookstore seemed to have an answer.

“So far the market can take all these bookstores but I believe the market is close to getting saturated,” said Wassef.

In 2002, Wassef and her sister inaugurated the model of western-like bookstores by opening the first Diwan in Zamalek. Building on the success of their first stint, the owners established a chain with ten outlets in Cairo and Alexandria. Since then, bookstore brands have become a remarkable phenomenon.

Yet, these brands navigate a resilient market where only 1.2 million households read books, according to a study released six months ago by the Information and Decision Support Center, a state-run think tank. Most Egyptians are averse to reading and blame their attitude on time constraints and low income, added the study.

“It is true that few people read books but in the last ten years the numbers have risen,” said Aladly from Alef.

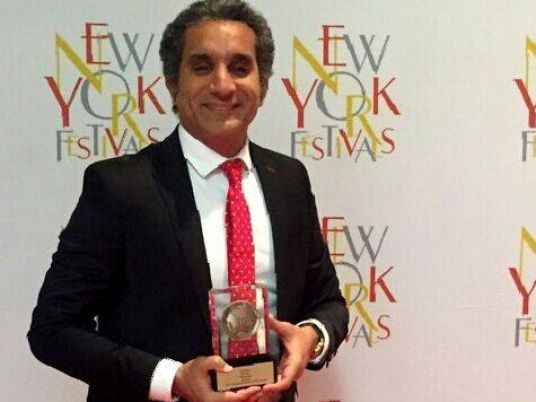

There are no statistics on changes in book readership but many bookstore owners affirm books have become popular especially among young Egyptians in recent years. Political satire has come to the fore as the most attractive genre, making up 40 percent of the sales of some bookstores. However, contemporary fiction remains on top at some other stores.

“Most of our customers are between 16 and 30 years of age,” said Aladly adding that their interest in books is related to the emergence of many small publishing houses in the last three years. Many of these houses are run by young writers and activists, who have developed a symbiotic relationship with book outlets.

“If Diwan and Kotobokhan had not been there to advertise my books and pay me regularly, I would not have existed,” said 28-year-old Mohamed el-Sharkawy who co-founded Malameh publishing house three years ago. Malameh has issued 65 titles including last year’s controversial graphic novel Metro, which was banned for its sexual content.

Nevertheless, Alef owners offer a controversial explanation as to why books have become popular. According to Ahmed Rahmi, an Alef co-founder, buying books is becoming a “a fashionable” pastime that people brag about, rather than a genuine interest.

To prove his point, Rahmi relies on evidence gathered from a survey at various universities and companies two years ago, which he conducted with two partners as part of a feasibility study.

“It is not that more people are interested in reading. One young man told us he does not read the books he buys but he likes to say that he owns these books.”

The capital required to start up a bookstore business can range between LE750,000 and LE6 million. Patience is also a must as it takes a minimum of four years to break even. As for the margin of profit, it is somewhere between 10 and 15 percent per book.

This business is more about providing a cultural service than generating rapid and excessive profits, said Rahmi.

Despite their claims to act as centers of “enlightenment”, these bookstores remain concentrated in Cairo’s richest neighborhoods, including Zamalek, Heliopolis and Maadi as well as opulent summer resorts along Egypt’s Northwestern Mediterranean coast. They seem to target a small niche of readers who can afford to shop for expensive Arabic and foreign books while sipping a cappuccino and savoring a marble cake.

“Books are very expensive. If I open a branch in a modest neighborhood, the project will be a failure,” said Rahmi, adding that the vast majority of Egyptians, 20 percent of whom live below the poverty line, cannot afford to buy Arabic books priced between LE15 and LE50.

For Diwan’s founders, the target audience was determined from the beginning. “I will not lie to you,” said Wassef .“When we opened we were targeting educated classes, people who travel abroad, with a particular income and who are following foreign releases.”

But as competition is getting harsher in Cairo, Wassef and some of her counterparts are contemplating searching for new markets outside the capital city and targeting readers with thinner wallets.