“I didn’t go back to using old photography techniques,” explains photographer Ahmed Rady. “I never used digital photography to begin with.”

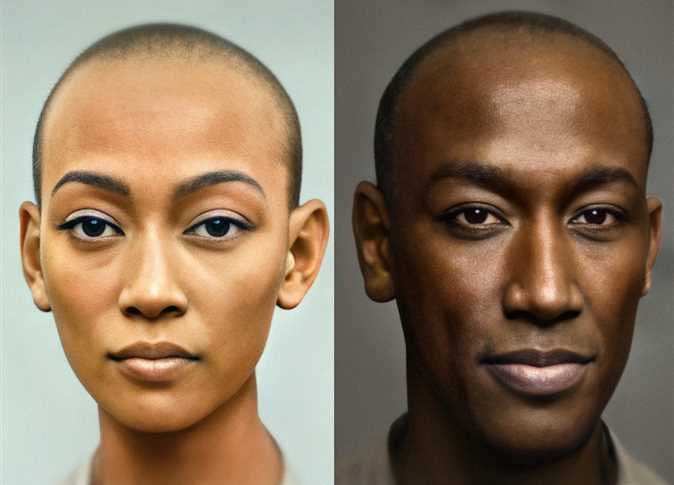

Displaying his modern hand-colored portraits of peasants and children, Rady recalls the stories behind each portrait. From the little girl who demanded he take her photograph, to the peasant whose brown mud house he transformed into bright green–Rady’s photographs are not simply throwbacks to the early twentieth century where black and white photographs were colored by skillful artists aiming at a realistic touch.

“Sometimes I pick colors that make the photograph totally unrealistic,” Rady comments. He displays an example: The scene is that of a smiling man in a white gallabeya standing against his mud house holding a flower and was taken on the Nile island Bein el-Bahryein, literally meaning “between two seas,” in Giza district. “I colored his mud house green because this is the color of the village. There are no cars, you have to reach it by a small felucca. This man is surrounded by water and greenery which makes him content. This is his heaven,” says Rady.

Though he never studied photography formally, Rady’s talent started to flourish at the age of 15. He studied law, graduating in 2004, and during his college years Rady documented–in black and white–numerous on-campus demonstrations. This work became the content of his first photo exhibition held at the French Cultural Center in Heliopolis. Soon his passion for black and white photographs grew to include hand painting, a coloring technique that opened the door for limitless creativity.

Hand coloring was popular in Egypt some 50 years ago before the mass production of color negatives. Renowned photographers such as Lehnert and Landrock as well as Van Leo who lived in Egypt during the early twentieth century often used the technique. “Hand coloring is a mixture between photography and painting,” Rady says. There are various types of colors: powder or transparent, but he prefers the aquarelle. After developing the black and white photos, Rady uses either a cotton bud or a fine paint brush and adds the shades of his choice, after diluting the colors with drops of water. To make it permanent, he subjects the photographs to water vapor.

Rady has also started creating his own settings. “The flower I added to the photograph of the man in front of his house reflects the studio, but the setting is outdoors”–a set up that resembles the street studio popular in the early twentieth century.

But why use such old techniques when the effects can be easily reproduced by computer?

“Because photography was more sensitive prior to the machine invasion,” Rady explains, emphasizing that hand painting is a human skill and a value in its own right. The personalization, the time spent makes it a very special memory. “I am trying to save the value of the creative human touch with no machine as medium. We have to keep that human touch.” From a technical perspective, Rady notes that digital photography might be advanced, but somehow lacks the depth of manual/standard photography.

Photoshop has sharp deliniations between various colors, unlike the smooth and imperfect hand strokes in manual hand painting. Rady is among the few who cherish and practice this form of art in Egypt, joining the ranks of the Youssef Nabil, a US resident, and Ihab Abdel Latif, currently living in Spain.

Working with a manual 50 millimeter lens with no zoom option, Rady’s photos are the results of personal encounters, and it is the relationship that he manages to reflect in all his work, for he needs to be at a close distance to his subject. “How you view your subject and whether or not they are tense, will show in the photos.”

Rady remembers one of his latest photos showing a young girl standing against a wall with her arms folded, looking right at him. This was taken in the village of Kamshish in the governorate of Monufeya while attending a conference held to resolve a feud between the landlords and the farmers, attended by human rights and legal activists.

“The conference was held beyond this wall and all the girls refused to be photographed. Except this one. She came to me with her arms folded and demanded that I take her photograph. It captured the air of rebellion that stirred this small village, hence the colors red and green,” Rady says.