The Ministry of Communications this week announced new restrictions pertaining to the use of text messaging for the dissemination of cellphone news alerts. The announcement comes on the heels of the abrupt closure of several satellite channels, the sacking of television talk show hosts, and the firing of Ibrahim Eissa, the outspoken editor-in-chief of independent daily Al-Dostour.

Notably, the announcement also comes immediately ahead of parliamentary elections scheduled for next month.

On Tuesday, Minister of Communications and Information Technology Tarek Kamel declared, “We don't intend to restrict SMS service providers.” He added: “We're only regulating their legal status.”

Kamel went on to say the decision aimed at limiting “inappropriate SMS content,” such as sectarian incitement, disinformation and inaccurate information pertaining to Egypt's stock market.

The restrictions will not be applied to individual private users or personal text messages.

In order to control alleged sectarian incitement and misinformation, the ministry has decreed that all news agencies and officially recognized political parties that employ mass text messaging services–also known as SMS aggregators–obtain government authorization in order to continue providing mobile-phone news alerts.

Under the new regulations, all political movements that do not enjoy official party status–such as the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt's largest opposition group; the National Association for Change led by liberal reformer Mohamed ElBaradei; the pro-democracy Kefaya movement; the Nasserist Karama Party; and the moderate Islamic Wasat Party–will all be denied access to mass text messaging services.

Ministry spokesmen could not be reached for comment, but reports indicate that news outlets utilizing mass text messaging services will have to pay hefty fees–in the tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds–within the next few days in order to maintain the service. Although officials at the Communications Ministry claim the decision is "non-political," security sources suggest otherwise.

Weeks earlier, a security source–whose name is being withheld because he is not authorized to speak with the media–told Al-Masry Al-Youm: “There have been security discussions relating to the monitoring of mass text messages by service operators for the past several months.” He added that discussions had "focused on means by which to limit and control the transmission of provocative and opposition text messages.”

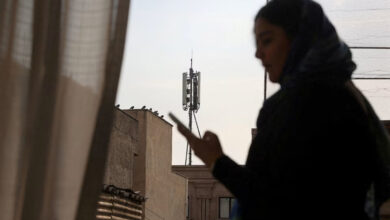

In August, human rights reports indicated that the Ministry of Interior was also moving to police and monitor Facebook accounts in Egypt. Over 60 million Egyptians are said to own/use cellphones, far more than those owning computers or who have access to the Internet.

Alert Coordinator Sherif Azer of the International Freedom of Expression eXchange told Al-Masry Al-Youm: “This decision affects not only news outlets and political parties, but also human rights organizations and NGOs that use mass SMS services.” Both service providers and users, he added, "will be negatively affected by the decision."

Azer went on to say the decision “aims at controlling and limiting the access to news updates in Egypt, thus restricting the information available about elections and human rights violations, along with a host of other vital information.” He noted, however, that websites, blogs and social networking tools–such as Facebook and Twitter–may still be used to disseminate information.

According to Azer, the timing of the move is relevant. “All the media crackdowns and information blackouts taking place right now are happening due to the upcoming elections," he said. "These are decisive elections and fierce competition is expected.”

The government, Azer believes, is using the issues of sectarian tension and misinformation about stock markets “as a pretext to crack down on the freedom to access information.” He added: “The decision is nonsense. It constitutes a violation of international human rights standards.”

"But we have yet to see how the government will implement the decision," he added. "Then we can determine the extent of the violations.”

In 1948, Egypt signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 19 of which stipulates that "everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers; either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice."

Furthermore, in 1982, Egypt ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 19 of which lays down provisions almost identical to those of the UDHR. However, the ICCPR also stipulates that “this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: For respect of the rights or reputations of others; For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.”

Nasser Abdel Hamid, an activist and campaign coordinator affiliated with would-be presidential contender Mohamed ElBaradei and the reformist National Association for Change, argued that the new regulations represented a "political decision."

“This is the latest episode in a series of government-ordered media crackdowns," said Abdel Hamid. "The government sought to target and silence television presenters and talk show hosts, then it moved on to target Al-Dostour newspaper by sacking Ibrahim Eissa.”

He added: “Now they're tightening their grip on telecommunications by denying access to information via text messages.”

“These orders have been issued from above, from the highest governmental authorities, in order to impose a media blackout on everything related to the opposition–from ElBaradei to all other fields of activism,” Abdel Hamid asserted.

He went on to say that the new regulations were “unprecedented in Egypt's history. We've never before seen such a heavy-handed clampdown on the media.”