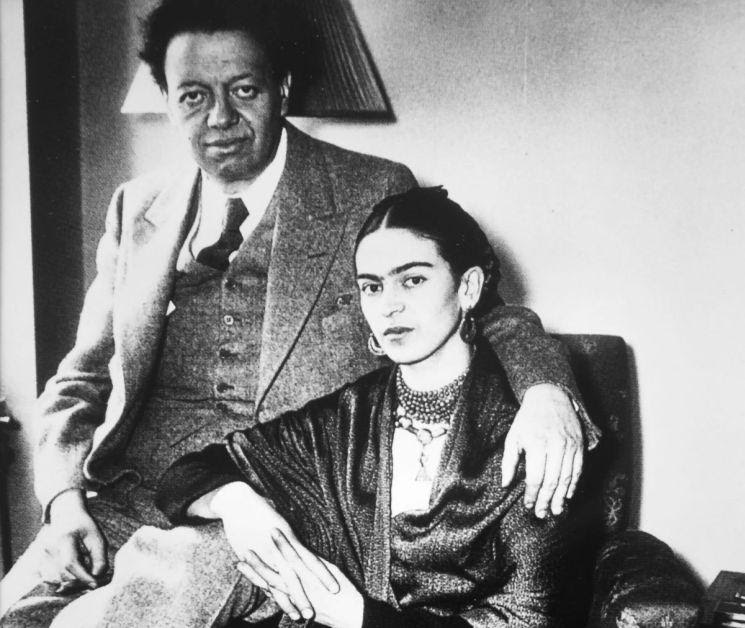

The love story of Mexican painters Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo has played out in books, opera and a Hollywood movie.

Mexico City is also a memory lane of their stormy romance, with murals and museums marking their early encounters, shared Communist ideals and intended burial in an archeological treasure house.

The epic begins in 1922 in central Mexico City when Kahlo, a teenager, spent hours observing Rivera, 21 years her senior, paint his first mural "The Creation" in her high school auditorium, today the amphitheater of the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso.

Kahlo's presence aroused the jealously of Guadalupe Marin, Rivera's second wife, the model for the mural's Eve-like nude. Rivera's autobiography recalls Kahlo brushed off her belligerent insults.

Six years later, and one block away at the National Education Ministry, Rivera was toiling on a three-floor mural, his biggest, when Kahlo approached for a critique of her artwork.

He soon cast Kahlo in the mural's fresco of an arsenal where she distributes munitions under a hammer-and-sickle banner. Rivera was then a Communist Party member, and Kahlo joined it after their 1929 marriage.

Shades of a marital crisis – his affair with her younger sister Cristina – appear six blocks away in Rivera's National Palace mural.

A panorama of Aztec life, Spanish colonial depredations and a paean to rebellion, the mural glamorizes Cristina as a benevolent educator, seated with her children, her fair skin glistening and green eyes translucent.

Standing behind, as if secondary, Kahlo looks dowdy, her expression blank and complexion a dull brown.

Heartbroken by the affair, Kahlo's self-portraits took a lacerating turn, symbolized in extricated hearts, sheared hair and a torso-piercing spear.

The couple divorced in 1939 but remarried in 1940.

In 1947, he portrayed Kahlo as a mother-like figure to his childhood self in “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central”, housed at the Diego Rivera Mural Museum one mile (1.5 km) west of the National Palace.

Looking protective, Kahlo rests a hand on the shoulder of Rivera, depicted as a boy hand-in-hand with a skeleton. Cupped in Kahlo's other hand is the yin and yang symbol of complimentarity.

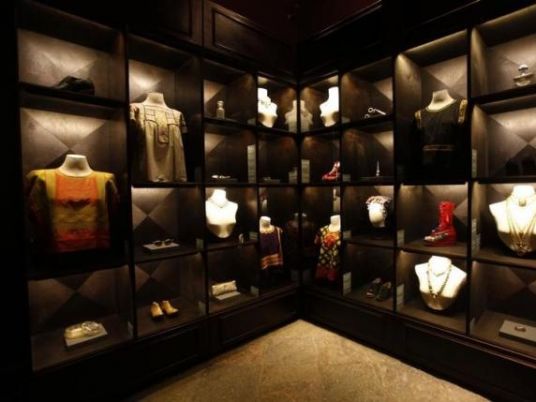

To the south, in the leafy Coyoacan district, is her Blue House family home. Now the Frida Kahlo Museum, it is a mecca of memorabilia visited by over 350,000 people last year.

Its current exhibit, sponsored by Vogue, showcases Kahlo's dress designs and colorful garments, largely inspired by natives of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and notes her influence on contemporary couturiers like Jean-Paul Gaultier and Givenchy.

The couple’s other residence, also a museum, is in adjacent San Angel.

Its separate him-and-her house-studios are linked by an aerial footbridge.

Rising on a lava bed 8 km (5 miles) west is Rivera's pyramid-like Anahuacalli museum built with volcanic stone. It displays more than 2,200 archeological artifacts.

Rivera instructed he and Kahlo be interred there in side-by-side niches.

She predeceased him, dying in 1954 at the age of 47. He lived another three years. Against his wishes, he was buried in Mexico's Rotunda of Illustrious Men. Kahlo's ashes stayed at the Blue House.