On Wednesday, January 8, Egypt announced to the world one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in Luxor.

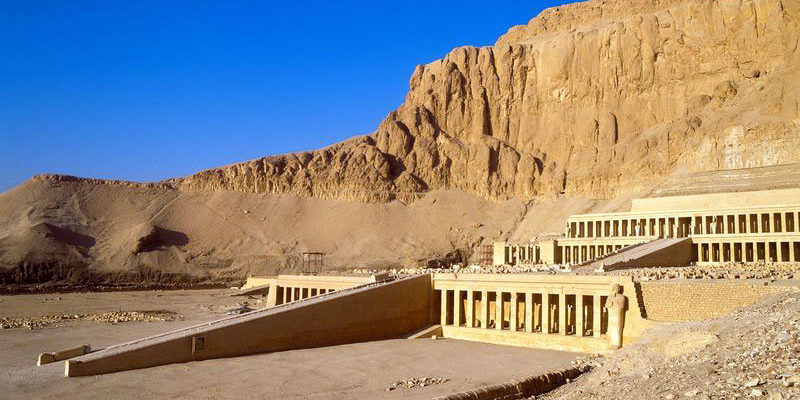

Numerous media representatives from various outlets traveled to Luxor to cover the important discovery, made near the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri.

Both Reuters and AP news agencies spread the news of this discovery to all news agencies.

Even if we had spent millions of dollars on advertising, Egypt would not have received such positive publicity as it did when we announced the details of these new discoveries from Luxor’s West Bank, which continues to astound the world with their unparalleled artifacts.

Governor of Luxor, Abdel-Matallab Emara, the Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Mohamed Ismail, and I, as the head of the Egyptian mission at Luxor’s West Bank, participated in the announcement of this astounding archaeological find.

This discovery includes royal artifacts that have not been revealed since the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb on November 4, 1922.

It will go down in history that on January 8, 2025, one of the biggest archaeological discoveries that astounded the world was announced – marking the beginning of a prosperous year for our beloved Egypt.

The assistant archaeologist overseeing the excavations, Tarek al-Awady, also organized a magnificent press conference.

He, along with the mission members, including archaeologists Abdel-Ghani al-Saidi, Mustafa Abdel-Shakur, and Mohamed Mohamed Mahmoud, the remarkable restorer Ahmed Farag Allah, and the talented artist Anahid Hassan responsible for archaeological drawings, utilized one of the newly discovered large rock-cut tombs at the site to display the discovered artifacts in a museum-like manner.

Employing advanced techniques, they preserved the larger artifacts, such as sarcophagi and massive carved and colored stone blocks, within their original niches and chambers in the tomb.

Smaller artifacts, including paintings, statues, and ritual tools, were displayed in showcases along the main corridor of the tomb.

All those who attended the announcement expressed their amazement at the beauty of the discovered artifacts and the impressive display that allowed them to appreciate the significance of these pieces while protecting them from visitors, similar to advanced museums.

During the conference, I expressed my gratitude to everyone who contributed to the success of this archaeological mission, which I am proud to have led for the past three years, working tirelessly in front of one of the most magnificent Pharaonic temples.

Egypt’s recent discovery at the Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahri is of paramount importance. We have unearthed over 1,500 limestone blocks, many of them inscribed and painted, from the valley temple associated with Hatshepsut’s magnificent funerary temple, known as ‘Djeser-djeseru’ or ‘the holiest of the holy.’

Additionally, we have discovered more than 100 stone tablets made of limestone, sandstone, and granite, exclusively inscribed with the cartouches of Queen Hatshepsut, including her personal name ‘Hatshepsut,’ meaning ‘the foremost of noble ladies,’ and her throne name ‘Maatkare,’ meaning ‘truth is the soul of the god Ra.’

These tablets were buried beneath the floor of the valley temple.

Among the most significant finds bearing the queen’s name was a limestone tablet inscribed with the name and title of Senenmut, the overseer of the royal palace of Hatshepsut.

This discovery confirms that it was Senenmut, and not the high priest of Amun, Habu Senmut, who built the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. We also found depictions of the queen performing religious rituals, such as the ‘Heb Sed’ ceremony, and scenes of her co-regent, Thutmose III, offering incense to the gods.

These depictions and the accompanying texts provide invaluable insights into the religious practices and iconography of the New Kingdom.

The mission has also uncovered a complete burial cache belonging to Queen Hatshepsut, containing various ritual and symbolic objects made of wood, colored pottery, woven baskets, and bronze.

Many of these objects were inscribed with the phrase, “The good god Maatkare, beloved of Amun, in Djeser-djeseru.” This newly discovered cache joins a series of similar finds made by previous missions led by scholars such as Schiaparelli, Herbert, and Howard Carter.

These discoveries represent a significant contribution to our understanding of ancient Egypt and the reign of Queen Hatshepsut. They provide new insights into her religious beliefs, the construction of her temple complex, and the artistic and cultural achievements of her era.

The second archaeological discovery that has captivated the world is the tomb of a high-ranking official dating back to the reign of Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th Dynasty who expelled the Hyksos and reunified Egypt around 1550 BC.

Despite its modest exterior, the tomb, constructed of well-preserved mud-brick with a layer of white plaster, reveals a wealth of historical information.

It consists of a small open courtyard leading to a short, arched entrance. Inside, a square chamber features a shallow shaft in the eastern part that leads to a small burial chamber.

One of the most significant finds in the tomb is a rectangular limestone stela with a curved top, adorned with a beautifully carved relief. The stela depicts the official seated at an offering table, inhaling the fragrance of a lotus flower. The inscription above the scene reads: “Year nine of the reign of His Majesty the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nebpehtire, giver of life,” referring to Ahmose I.

Beneath the scene, the inscription continues in two vertical columns, listing the offerings presented to the deceased.

Five horizontal lines at the bottom of the stela detail the offerings made to the god Osiris, Lord of Abydos, and the god Ptah-Sokar, Lord of the Necropolis. The inscription mentions specific offerings such as bread, beer, oxen, fowl, linen, alabaster vessels, incense, and perfumed oils.

It also includes a heartfelt dedication from the deceased’s friend, a chariot commander named Khutymes, who had commissioned the stela.

We have thus unearthed a rare funerary stela that provides a unique glimpse into the life of a high-ranking military officer during the reign of Ahmose I.

This discovery, along with the ongoing excavations, sheds new light on the early years of the 18th Dynasty and the foundation of Egypt’s Golden Age.