A spokesperson for the ruling military council on Wednesday announced that Egypt will not allow international monitors of the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections, describing it as an issue of Egyptian sovereignty. But many critics say the government has so far failed to meet basic logistical requirements for holding elections and may be taking steps to cover up potential election fraud.

Mona Seif, an anti-regime activist, believes that decision denotes the military's intention to back specific political groups that also rebuff international monitoring, such as the Muslim Brotherhood.

Meanwhile, a smear campaign is underway accusing groups of receiving foreign donations, thereby affecting confidence in NGOs that monitor elections.

Bahey Eddin Hassan, director of Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) argues that Egypt's rejection of foreign observation indicates that ruling military council is aware of potential problems, which it does not want monitors to detect.

Logistical problems cast shadows over the referendum on constitutional amendments in March, which was viewed as Egypt's first genuine vote.

The number of referendum supervises was not enough to cover all polling stations, according to Seif, who said, "Some constituencies did not even include enough polling stations."

Seif said some voting units did not have sufficient ballots, which she describes as an "obvious example of bad management by the government.

“There are several logistic measures that should precede elections day," she said. "Those include preparing voters' lists, dividing constituencies and polling stations and training the employees who will supervise the process. Those are the basic factors for transparent elections.”

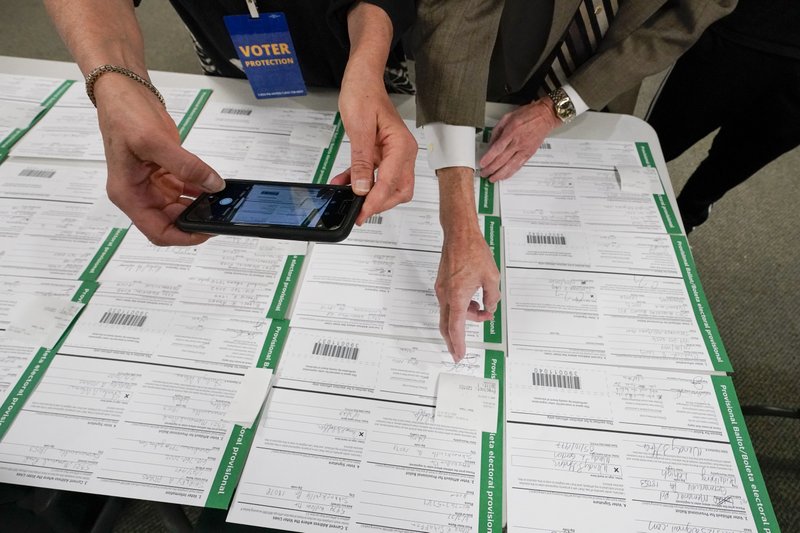

Human rights groups reported voting irregularities during the referendum. They attributed the flaws to an insufficient numbers of judges at polling stations in a number of governorates, as well as to the failure of the judicial committee responsible for supervising elections to make necessary preparations. The committee had to print out extra voting forms, which led the referendum to halt for a long time.

Negad al-Borai, a prominent lawyer and a human rights advocate, fears that the problems witnessed during the referendum might worsen during parliament polling which, he explains, involve many more polling units.

He expresses his doubt that the government had taken any measures to avoid technical or logistic failures before or after the elections.

Borai stresses the need to change the prevailing mentality that dominate judges involved in the electoral process, along with employees at polling stations who became accustomed to forgery.

Meanwhile, a joint report released by a number of Egyptian civil society groups criticized members from the disbanded National Democratic Party (NDP), the Muslim Brotherhood, and Salafis for providing material incentives to voters to sway them in favor of the constitutional amendments. It also slammed interference by employees at polling stations who the report alleged instructed citizens to vote "yes."

Citizens are expected to vote with their ID cards serving as identification as was the case with the referendum. The IDs replaced special voter registration identification, which observers labeled as one of the tools utilized by Mubarak’s regime to manipulate election results.

But Hassan said that with Egypt's security still unstable, it will not be possible to control the elections, which he predicts will witness heavy violence.

Elections in 2005 and 2010 saw violent encounters between supporters of rival candidates, especially in Upper Egyptian constituencies, where tribal allegiances dominate politics.

Constitutional amendments approved through the March referendum were included in an interim constitution that stipulated complete judicial oversight of elections.

A popular poll in 2007 had resulted in the cancellation of judicial oversight, among other changes. The poll, which observers described as rigged, helped lay the groundwork for rigging the 2010 parliamentary elections, a precursor to the 25 January revolution. The formerly ruling NDP recorded a landslide win in the 2010 elections, taking more than 90 percent of seats.

The parliamentary race was supervised by a judicial panel appointed by the Ministry of Justice. The ministry assigned employees, instead of judges, to run polling stations and excluded independent groups from the monitoring process.

But those organizations had the opportunity to play a monitoring role in the parliamentary polls of 2005, during which the NDP won a majority of 72 percent of seats.

Those elections, however, were subject to full judicial observation, which helped track several cases of vote rigging in favor of NDP nominees. When the Mubarak regime pressed for official approval of elections results, several judges objected, calling for an independent judiciary.

Three days ago, the ruling military council formed a high judicial committee to supervise parliamentary elections. The committee includes a number of heads of appeals and cassation courts and will commence its activities on 18 September.

Hassan believes that the delay in forming this committee causes confusion and denies judges information needed for effective oversight.

A bill regulating upcoming parliament elections was approved by the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces on Wednesday. It stipulates that half of the 504 members of parliament should be elected through list-based candidacy, while the other half will be elected through the single-winner system.