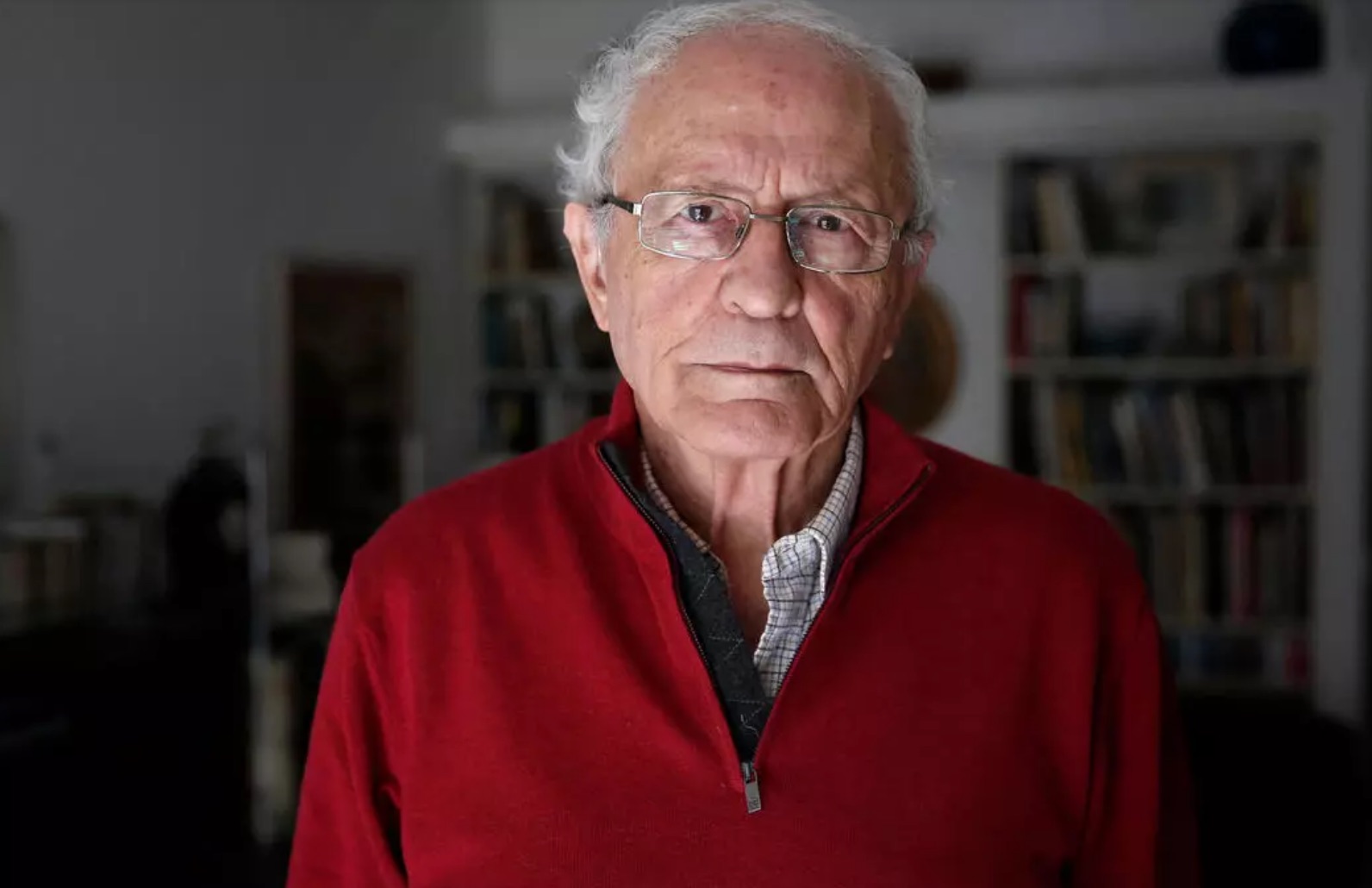

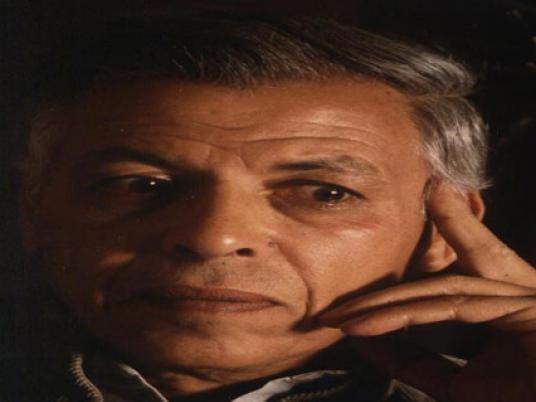

Mohamed al-Bisatie was born on a night of rains, thunder and lightning near Lake Manzalah in Daqahlia Governorate. He arrived on that night in 1937 thanks to the help of a midwife who almost came too late.

Bisatie related these moments from his childhood in his autobiography “And the Train Comes,” noting that he was such a curious toddler, so bent on exploring every nook of his village, that his mother resorted to tying him to a peg in the courtyard.

The curious and gifted storyteller died on Saturday after a protracted battle with liver disease, at the age of 75.

Bisatie left his north Delta village as a young man to study commerce — which was not his choice — at university in Cairo. He did not return to his village. “Never,” he once told translator Denys Johnson-Davies. But the shores of Lake Manzalah stayed inside him, growing and developing into the most significant, gentle and beautiful wellspring for his stories and novels.

He began his writing career with short stories, publishing his first volume of at the age of 31. His works were typically pithy, often humorous, sensuous and memorable, earning him the title of the “poet of the short story.” He used the same poetic, episodic tools in his novels. During his 30-year career, he published a number of short-story collections and more than a dozen novellas and novels. The haunting “Houses Behind the Trees” (1993/1997) was his first full-length work to be published in English translation, by Johnson-Davies.

However, Johnson-Davies said that Bisatie’s true contribution was to the Arabic short story.

“I think that it was as a writer of short stories that he showed his real talent,” Johnson-Davies said over email. “He made no concessions to his readers and one felt that they either really got inside his stories or [they didn’t. And] he couldn’t care one way or the other.”

“Clamor of the Lake” (1994) is perhaps Bisatie’s most celebrated long work. “Clamor” won the 1994 Cairo International Book Fair award and was voted one of the “best 100 novels” of the 20th century by the Arab Writers Union. The poetic novel brings the shores of Lake Manzalah to life in what novelist and critic Youssef Rakha has called an “epic prose poem whose hero is a place.” Its translation, by Hala Halim, was runner-up for the inaugural Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation in 2006.

Halim, over email, called the loss of Bisatie a “huge blow.”

“Words like ‘nobility’ and ‘magnanimity’ may seem threadbare, the stuff of obituaries. I will always remember an evening at the very end of 1994 when I started reading his just-published novel ‘Sakhab al-Buhayra’: I could not put it down and wished the opportunity would arise for me to translate it. It will always amaze me that, some months later, he instantly accepted that I, who had hitherto only published translations of short texts, should translate his masterpiece that won the Cairo International Book Fair’s award for Best Novel of the year,” Halim said.

However, despite this and a number of other laurels — which included an Owais Prize in 2001 and a Sawiris in 2008 — Bisatie was not as celebrated as his literary peers, and only won a State Incentive Prize in 2012, a little more than two weeks before his death.

“I think that Mohamed didn’t make the necessary moves to gain the fame that other — and perhaps less talented writers achieved. For me he was very much a writer’s writer,” Johnson-Davies said. “I feel that he has made a real name for himself without really making the sort of social effort that many writers are prepared to make.”

Halim added that Bisatie was “aesthetically, ethically and politically incapable of compromise … [and] took his stand through the bleakest Mubarak years away from the limelight.”

A number of critics believed that Bisatie’s focus on village life was limiting. Even Johnson-Davies wrote encouragingly in 1999, “He possesses the imaginative talent to strike out wider.”

When Bisatie did strike out wider, it was not always successful. He had spent a number of years working in the Gulf, and used that space as a setting for his 2006 novel, “Drumbeat” (AUC Press 2010). Although the novel’s premise is surreal and compelling — all Emirati citizens leave to go watch a World Cup game, and the country’s migrant workers are left in charge — it falters on follow-through, failing to create a vivid picture of the unnamed “Emirate.” The book does its best work when it follows migrant workers back to their Egyptian villages.

Although Bisatie, in his later works, also sharply portrayed other spaces, such as prisons and the “informal” communities of Egyptian cities, his work was most comfortable in the village. This was true of his “Hunger,” shortlisted for the 2009 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (also longlisted for the 2011 Prix-Courrier and translated into English by Johnson-Davies), and in his final short story collection, “Small Butterflies,” published in 2012 by Dar al-Hilal.

Bisatie will also be remembered as a man of principle.

“Bisatie breathed his commitment to social justice and human dignity into masterly fictions that are a signal contribution to Arabic and world literature,” Halim said.

And, in the words of Johnson-Davies: “It is a great loss for Egypt and for the Arab world.”