Workers perched on scaffolding delicately repair Cairo’s 13th-century al-Zahir Baybars mosque, a vital restoration project in the Egyptian capital’s neglected Islamic quarter.

Halted by the popular protests that toppled dictator Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and the ensuing political and economic turmoil which enveloped the country, restorative work on the Mamluk-era mosque picked back up last month.

On the other side of the quarter, similar work on the 14th century al-Maridani mosque has just begun.

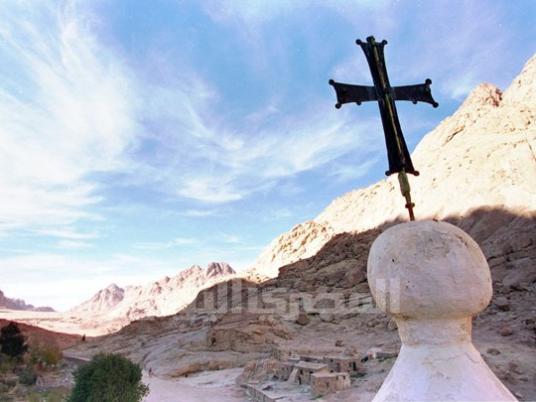

The capital’s Islamic quarter, a Unesco World Heritage Site since 1979 often referred to as historic Cairo, boasts some 600 listed monuments.

‘Rapid deterioration’

In the immediate aftermath of Mubarak’s 2011 fall, many of the area’s squat traditional buildings were torn down and replaced with structures of six to eight floors.

Meanwhile, rampant theft saw centuries-old objects disappear from mosques.

And even if looting and illegal construction have since decreased, according to authorities, the historic heart of Egypt’s teeming capital of 20 million is still choked with pollution, its streets cluttered with rubbish.

Unesco has warned several times in recent years of increasing degradation in historic Cairo, raising the alarm as it has for many other heritage cities across the globe.

In 2017, its World Heritage Committee urged Egyptian authorities “to take all needed measures to halt the rapid deterioration” of sites across the quarter.

In an October visit to monitor new restoration work, Antiquities Minister Khaled el-Enany highlighted budget issues as one of the central challenges facing the district.

“It’s always said that Islamic antiquities are in bad condition. It’s a fact,” he said, adding that failing sewers and monuments in residential areas had also created issues.

The antiquities ministry is fed by revenues generated at Egypt’s wealth of historic monuments.

And while tourism has picked up since it dropped in 2011, the 8.2 million people that visited Egypt in 2017 are still far behind the country’s 14.7 million visitors in the year before the uprising.

With earnings from the sites down, much of the restoration work has been dependent on foreign funding.

Kazakhstan is putting up $5.5m to finance work on the Baybars mosque.

Meanwhile, the European Union is contributing $1.3m for the al-Maridani mosque, in tandem with the Aga Khan Foundation which has put forward $151 000.

From his renovated home in historic Cairo, architect Alaa al-Habashi said time was of the essence in the push to preserve the area.

“It cannot wait… if we want to stay on the World Heritage List there is not a minute to lose,” he said.

The only way to effectively combat the decay, he said, was “to get citizens involved”.

From his 16th-century home, known as Bayt Yakan, Habashi runs an art collective and organizes conferences around the “revitalization of the historic city”.

‘A big challenge’

The Aga Khan Foundation has designed a similar project, although on a much bigger scale, around the al-Maridani mosque.

It includes the creation of a touristic route through the neighborhood and training for residents on accommodating tourists.

“This will generate economic activity, tourism… but the project also has a social dimension,” said Ibrahim Laafia, head of cooperation with the EU’s delegation to Egypt.

But good work often runs up against bureaucratic hurdles.

All projects have to navigate the labyrinthine overlap of jurisdictions between local authorities in Cairo and the ministries of antiquities, tourism, housing and religious endowments.

In 2015, Cairo authorities created the governorate’s first department for the preservation of antiquities.

Its director, Riham Arram, said that while the city is making slow progress, preserving its history is still “a big challenge”.

“We have not managed to do everything. It’s true that there is still illegal construction… but we will continue,” she said, explaining reforms could increase fines for unlawful building.

“Now security has stabilized, the country is stable,” she said.