“Our folkloric instruments are dying,” says 61-year old, Egyptian musician Salama Metwally as he tunes his favorite rababa. He is wearing his traditional ensemble; a black kaftan overtop a gallebaya with his head wrapped in a white turban. His dress makes for a stark contrast against the sleek booths and modern decorum of the Cairo Jazz Club.

His “brothers” and fellow musicians, Ragab Sadek and Sayed Emam sit on either side of him. They both nod their heads in affirmation of Metwally’s statement.

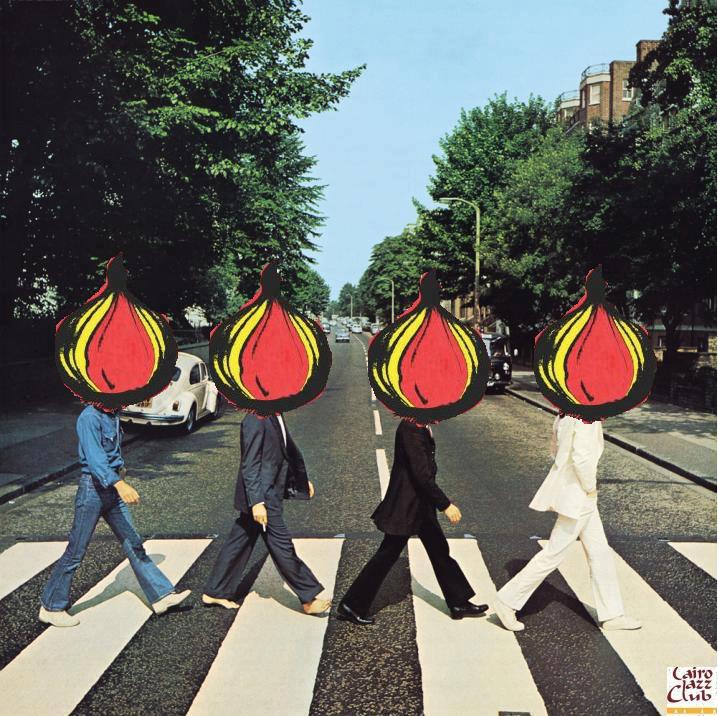

Although analog synthesizers and vinyl turntables may be badges of authenticity for many modern day musicians, for the five-man band that make up The Egyptian Project, it is all about delving into Egypt’s folkloric past in order to create new sounds for the future.

The Egyptian Project is an ongoing, cross-cultural musical collaboration that seeks to utilize traditional Egyptian folk instruments mixed with electronic sounds and compositions, including trip-hop, hip-hop, minimal techno and more. The project’s goal is to create an eclectic assemblage of world-class musicians who will continuously work together to explore unchartered musical territories.

“My idea was to combine electronic, acoustic and Egyptian traditional music to expand upon our known soundscape,” says producer Jerome Ettinger, the mastermind behind the Egyptian Project. “I wanted to create a family made up of string instruments, percussions, vocals, the rababa and arghul to tour with. I wanted to foster a new path for music and expose it to various countries throughout the world.”

For Ettinger, it all began with his discovery of the arghul some 15 years ago. He was attending a friend’s concert in France, when one of the musicians took to the stage with a strange instrument Ettinger had never seen or heard before.

The arghul can be traced back to the times of Ancient Egypt — the instrument has a tone similar to the clarinet, but it requires a difficult and specific breathing technique that takes years to master. It is a key component in making Mawwal music, which is traditional, Arabic folk music that is known to express the daily life of peasants from the delta region.

“Not many people in France, or in the world for that matter are professionals on the arghul, it is another dying instrument,” says Ettinger. “Then an opportunity came about which allowed for me to go to Egypt and learn the instrument under the auspicious of acclaimed arghul master, Mustafa Abdel Aziz.”

He goes on to mention that Abdel Aziz was famous for his recordings with the Egyptian orchestra, particularly with his interpretations of Mozart, in addition to his work with renowned international musician, Peter Gabriel.

It was around this time that Ettinger also met Ragab Sadek, who was already widely known as being a virtuoso of percussions. Sadek is often cited as being a major reference for traditional Egyptian music and has mastered several instruments including the tablah, doff, riq, and zills (finger cymbals).

After some years spent in and out of Egypt, Ettinger went on to form the folk-fusion band, Zmiya. The group was known as an electro-world music band that occasionally explored Egyptian melodies, rhythms, lyrics, and tones.

“It was through this band that I became more deeply fascinated by Egyptian folk music,” explains Ettinger. “Also, I could not believe how so many of these traditional instruments were rapidly dying, but yet I had met Ragab and Salama, who were both such masters of their instruments — I wanted to find a way to survive their music while also creating new, original sounds.”

The Egyptian Project officially launched nearly five years ago with the aim of assembling a group of musicians to execute Ettinger’s vision for cross-cultural collaborations.

Ettinger mentions that it still took some time to figure out all the proper musical components and members, but that the pieces eventually fell into place once Sadek agreed to join the group. With Sadek, came along his musical friends, Sayed Emam and Salama Metwally. All three men are members of the Musicians of the Nile governmental group and have played music together for close to 30 years.

The idea was originally to create band that could tour the world, but soon after sitting down for countless studio sessions the collective decided they would also record and produce the project’s debut album, “Ya Amar” (The Moon).

“This was not the first time we have all worked with western musicians,” says Sadek. “But this time, the output, the process and the synergy was much better for two reasons. The first is that each member is truly a professional and master of their instruments, secondly, the duration of time we spent together helped us to overcome many of our original obstacles.”

“You see what happens when you play together for some years, it becomes a lot like cooking a new recipe – you add some salt, you take away some pepper, throw in a little cumin and you keep tasting it to make sure it is the best outcome. But you must work at it time and again to get it right.” says Sadek.

The members of the project also credit vocalist, Sayed Emam with much of the group’s successful sound. They unanimously mention that Emam is more than a vocalist and describe him as “one of the best lyricists of our times.” While Emam is more widely known for his vocal capabilities, he is also a composer and master of the kawala, a slanted clarinet-like instrument prominent within Arabic folk music.

For Emam, one of the more difficult tasks in the project was staying within the standard measures and counts known to electronic music, which differ greatly to the elongated stretches of traditional Mawwal musical structures.

This past week, the Egyptian Project members performed their debut album, “Ya Amar” in Cairo and Alexandria. And while all their performances were extremely well received, the most lively and engaged performance can certainly be pinned to the Cairo Jazz Club show.

The group’s performance was arguably one of the best shows to hit the Jazz Club this year. In front of a packed house, the band members blended together some of the most unique combinations of music including trip-hop and reggae infused with Emam’s grand and penetrating voice.

But what is even more impressive was each member’s brilliant showmanship. These guys are truly professional. When watching Metwally on stage, it is difficult not to become instantly mesmerized by him as he switches seamlessly from the rababa to the violin. It may also have something to do with his incredible ability to dance with his instruments, while luring audience members closer to the stage through his trance-inducing aura.

The group’s ability to interact with the audience, in addition to their musical mastery places them in a league of their own when comparing to other cross-cultural collaborations.

“Instead of letting beautiful, folkloric instruments like the rababa, arghul, and kawala die, we can use them to make entirely new sounds. By adding effects onto each of the instruments, or changing their construction and wasting nothing; we can modernize the instruments and hopefully, prolong their life and their heritage,” says Ettinger.

Emam also agrees with this method — for him all the answers can be found in the music of Om Kalthoum, Abdel Waheb, Abdel Halim Hafez, Farid al-Atrash and the many other artists who make up Egypt’s musical heritage.

“Just because there is new music being made, does not mean we have to kill the old,” says Emam.

For more information on the Egyptian Project and the tour dates for “Ya Amar” please visit their website.