Irregularities, misallocations, dodgy deals and controversial contracts seem to be a common thread in state-owned land sales in recent years, with more and more stories of corruption coming to light.

The laundry list, getting longer with each new expose, either through parliament or the media, currently ends with the case of Madinaty, a large, gated compound lying on the edge of Cairo and owned by business mogul, ex-MP and former ruling party strongman Hisham Talaat Mustafa, who stands accused of murder in a separate case. The validity of his ownership of the 8000 feddans of land that house his real-estate project is under question.

The final verdict is due on 14 September, according to a decision by Egypt’s top administrative court. The two men at the heart of this land sale scandal are Mustafa, considered to be Egypt’s biggest publicly-listed property developer, and former housing minister Mohamed Ibrahim Soliman, accused of squandering state money through similar questionable deals and contracts.

In Mustafa’s case, two separate appeals were filed simultaneously by Mustafa’s holding company and the New Urban Communities Authority in order to overturn a ruling that annulled the contract between the company and the state-run authority last June. The verdict was issued in response to a law suit filed by Hamdy al-Fakharany, an architect and urban developer, against Soliman.

Mustafa’s land deal, which smells of corruption and nepotism, is only the latest in a series of scandals that involve public funds laid to waste, or big businessmen being granted land at half or quarter the real value.

Earlier this year, the Egyptian government sold to Saudi royalty and billionaire Al-Walid bin Talal 224,480 feddans of land in southern Toshka–only 100,000 of which were publicly declared.

The rest of the land was given to Talal, seemingly in secret, to act as “a buffer zone,” or protection for the land that was officially allocated to him for agricultural investment projects.

Analysts claimed at the time that the contract drawn up gave Talal rendered the state the “weaker party.” According to the terms of the contract, Talal paid LE50 per feddan, and received tax exemptions and discounted rates for water and electricity.

Some MPs even demanded that the land sold to Talal be recalled.

In March, however, Minister of Agriculture Amin Abaza came out and issued a public apology, tagging the deal with Talal “a mistake.” However, he said the contract could not be withdrawn, because it doesn’t set a deadline for the completion of Talal’s projects.

“But we have reached a compromise,” the minister said. “We will only supply him with the amount of water that is enough for each stage of the project he has completed […] Talal owns the land, but we have the water.”

In the same month, Talal revealed plans to sell to the public 50 percent of the shares of the company that was set up to develop the Toshka project.

The sale of land in Tut Amoun village, lying just beneath the High Dam in Aswan, is another case of misallocation that has resurfaced lately.

The land was sold in 2007 to a company, then the contract was broken and it was sold to another company, Palm Hills, in which current Housing Minister Ahmed al-Maghrabi owns shares. The scandal led President Hosni Mubarak to issue a decree to cancel the sale of the land, overturning a decision by the Minister and the urban authorities.

Following the incident, al-Maghrabi told the press that he didn’t feel any embarrassment when the President cancelled the contract, since the piece of land was “too close to the High Dam” and would be better off owned by a public company rather than a private one.

The president also called for a new law to govern land sales. The current law gives governors the right to forge deals with businessmen over land sales, and observers claim that the violations go as far as Atef Ebeid’s cabinet, which similarly misallocated strategic spots such as al-Dabaa. Sales of lands in Dahab and on al-Waraq islands are similarly disputed.

The current law also allows for the sale of public land whereby the buyer pays only 25 per cent of the total land value on sale and the rest in installments over a three-year period.

However, Muslim Brotherhood bloc member and MP Ashraf Badreddin told Al-Masry Al-Youm that the law isn’t the issue.

“There are no problems with laws, they’re there. The main problem are those in charge, it’s the corrupt officials. For instance, in the case of Talaat Mustafa, Soliman gave away the land knowing precisely that he was going against the law. This is a minister with an army of legal consultants. I’m sure they warned him after studying this sale, but obviously he insisted on going through,” said Badreddin.

Al-Fakharany, a small developer who was refused a bid of a 1000-meter piece of land by the urban authorities, cited legal “irregularities” during the sale, and said the land was not sufficiently open to public bidding as it should have been: It was considered to have violated laws governing tenders and auctions.

He claimed Madinaty received preferential treatment, and accused Soliman of squandering LE147 billion of state funds to benefit Mustafa. In earlier statements to Al-Masry Al-Youm, al-Fakharany said that Mustafa’s project “had enjoyed exceptions that were not seen by other undertakings.”

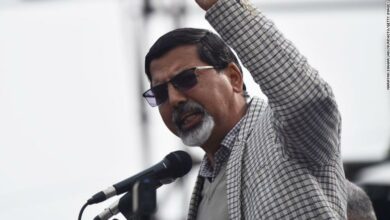

The case against Mustafa was however brought forward only a few months after a group of 45 parliament members filed complaints with the Public Fund Prosecution, police back in March. These MPs, led by Brotherhood MP Saad al-Husseini, claimed the former housing minister wasted between LE26 billion and LE102 billion of state money.

Observers, analysts and members of parliament differ on why such cases of “corruption” are now being revealed. However, most agree that the timing of the revelations, ahead of parliamentary elections and a year before the much-anticipated presidential race, is crucial.

The witch-hunt against businessmen and their government-appointed partners in crime is either a public relations spin to increase the popularity of a waning government scrambling to win votes, or a reaction forced from it due to mounting pressure from Egyptian citizens and opposition groups, say observers.

“Revealing these cases, and letting the media talk, gives a good impression. It says, ‘Here, we’re fighting fraud and corruption.’ It makes the government look good,” political analyst Yehia al-Gamal told Al-Masry Al-Youm.

According to Brotherhood MP Badreddin, his parliamentary bloc have been petitioning to discuss such land sales violations, including questioning the officials responsible, since 2005—such violations relating to over LE500 billion worth of land sold under both Soliman and al-Maghrabi, including land sold in southern Sinai by a “gang of officials and an ex-security chief.”

“But the parliament would never schedule such discussions. Only recently have they been compelled to. We’re so close to elections, and they can’t afford not to address this any longer,” said Badreddin.

“[…The NDP] blocked attempts to blow the cover of their men for years, through their parliamentary representatives. MPs from the ruling party have also vetoed reports citing violations to the public prosecution.”

According to contractor and urban communities expert Sabry Fawzy, sometimes the government leaks such cases in order to bring them into the spotlight, for them to present their defense and get the issue out of the way.

“They put their men in tight spots, and then free them, as everyone watches. By law. And quickly. So that, at least in the public eye, it looks like they haven’t done anything wrong,” said Fawzy.

But sometimes, according to Fawzy, the corruption is so deep and real that the government has no choice but to “sacrifice” one of its men–Mustafa being a prime example–“so that people would stop nagging.”

“They throw one of their own in the sea, to silence the people. This is not a shake-up in the business community […] The revelations are all part of a government strategy,” said Fawzy.

Al-Gamal agrees. “I believe we’re seeing these cases now, because of the proximity to the elections, despite my belief that the results of the elections are already decided. […] The government wants to distract people. And then all the hubbub will fade.”