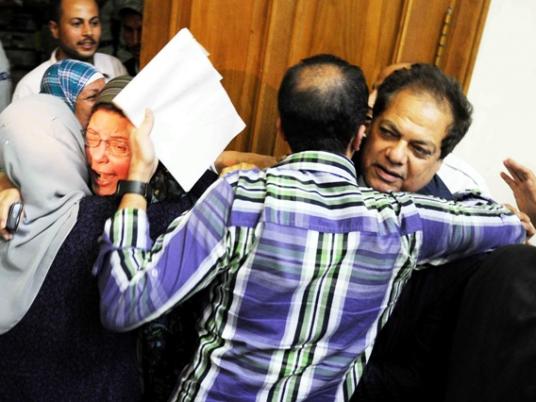

More than a thousand Ceramica Cleopatra workers protested outside the presidential palace last week, demanding unpaid wages, overdue bonuses and profit-sharing payments. Worker representatives met with presidential staff and newly elected President Mohamed Morsy to demand support in their battle with ceramics industry tycoon Mohamed Abul Enein.

Union delegates said Monday night that the president and his staff were “seeking a resolution to this impasse within the next 48 hours, God willing.”

Abul Enein served as an MP in Hosni Mubarak’s now-defunct National Democratic Party and as chairman of the People’s Assembly Industry and Energy Committee. Now he is confronted with protests and industrial action at his two companies, located in 10th of Ramadan City and Ain Sokhna.

Since the 25 January revolution, Abul Enein has been summoned for questioning in corruption cases but has not been found guilty. He still faces charges of instigating the armed attacks on Tahrir Square on 2 and 3 February during the revolution, an event often called the “Battle of the Camel.”

And as he has come under increasing legal pressure, Abul Enein has increasingly neglected his companies' workers.

A stranded whale

Ceramica Cleopatra Group, Egypt’s largest producer of tiles and sanitary ware, is also a regional and international exporter. In 1983, the first of Abul Enein’s factories began production in 10th of Ramadan City, outside Cairo. Over the years, the company grew and diversified to include several additional factories and employ some 4,500 workers.

Then, in 1999, the industrialist opened his second company in the port city of Ain Sokhna on the Red Sea. This company quickly became Abul Enein’s flagship enterprise, producing three times the capacity of his first company. It employs a workforce of about 5,700.

Apart from ceramics, Abul Enein is also involved in agriculture, tourism, real estate and media. Neither he nor his administrators were available for comment on this article.

Workers at Abul Enein’s ceramic companies say the industrialist is using his economic clout — by withholding wages and threatening his workforce with sackings and the closure of his companies — to bid for an acquittal in the Battle of the Camel trial.

“This whale of a businessman is using us, and his companies, to get himself out of the trial. He’s trying to send the authorities the message, ‘If you rule against me, I’ll take my companies down with me,’” said Mohamed Anwar, secretary general of the local trade union committee at Ain Sokhna Company.

But Anwar said Abul Enein would never liquidate the two ceramics companies and was just using them to “throw his economic weight around.” Apparently in response to his threats, a court has imposed a travel ban on Abul Enein.

“Abul Enein is trying to twist our arms, so we will twist his,” Anwar said. “We workers, at both the Ramadan and Sokhna companies, are resisting his injustices.”

Ragab Hussein, a worker at the 10th of Ramadan City factory, said the timing was no coincidence. He said Abul Enein has refused to pay his 10,000 workers their June monthly wages, which was due 1 July, because of his next court hearing.

Holding up signs, flags and banners, Hussein’s co-workers chanted “Abul Enein is a thief” and “If you manage to escape the Battle of the Camel trial, you will not escape the workers.”

“Beyond this trial, nobody knows Abul Enein’s real intentions,” Hussein said. “He might be trying to confront President Morsy, or perhaps he’s attempting to strike a deal with the new regime to retain his economic and political influence.”

Shouting in anger, two workers said Abul Enein spent LE7 million supporting Ahmed Shafiq’s presidential bid, yet was unwilling to pay his own workers’ wages.

Ghareeb Salah, a worker from Ain Sokhna Company, promised that workers would escalate their protests if their demands were not met. He said workers had blocked Al-Orouba Street that day for about half an hour.

“We don’t like to resort to such actions, but we must have the authorities hear our angry voices,” Salah said.

Since the revolution, thousands of Abul Enein’s factory workers have repeatedly protested. They launched their first strike at Ain Sokhna Company in early March of this year, where they demanded that the company fulfill a promise to institute profit-sharing arrangements.

On 16 March, Abul Enein entered into an arbitration agreement with his workers and the Manpower Ministry. He agreed to pay his labor force its overdue profit-sharing payments. However, he has only given his workers one installment of these payments and has not fulfilled other labor demands that he had pledged to meet at the ministry.

“We’re still producing at the factories, but we’re stockpiling the production and now allowing it to be sold,” Anwar said. “Until we receive our rights, we’re not allowing his trucks in at either company. We’re halting sales, distribution and export.”

Abul Enein imposed a lockout on Ain Sokhna Company for 11 days in May. He did the same at the 10th of Ramadan City Company during the first week of June. The purpose of these lockouts is not known. In response, workers demonstrated and blocked highways.

Thousands of workers at Ceramica Cleopatra are pinning their hopes on their newly established labor unions, while others hope the new president and his socioeconomic policies will help them.

Anwar recalled that he and a delegation of workers from Ain Sokhna Company met with President Morsy in mid-May while he was campaigning for president in Suez.

“Morsy listened to our demands and took note of our grievances,” said Anwar, who voted for the new president. “If Morsy neglects us or fails to uphold our rights, then we will take our protests to Arbaeen Square [in Suez] and Tahrir Square to topple him, just like his predecessor.”

Unions’ role

Yasser Hassan, an administrative worker at Ain Sokhna Company, said he believes labor unions might play a more important role in defending workers’ rights than the new president can.

“Our primary gains at the company have been the establishment of a union and increased wages,” Hassan said.

He said the union had fought for workers’ rights and managed to increase their wages from an average of LE450 per month in 2006 to the current average of LE1,300.

Emboldened by the revolution, the Ain Sokhna workers established their union in April last year, while the 10th of Ramadan City workers followed suit two months later.

Anwar said that the local union they had established was an affiliate of the state-controlled Egyptian Trade Union Federation, but that they could switch to an independent federation if necessary.

The situation at 10th of Ramadan City Company appears bleaker. Mokhtar Abdel Salam, president of the local union committee, said the company administration fired six out of seven unionists, including himself, as well as two other workers.

“The eight of us have been accused of instigating unrest,” said Abdel Salem. “When we demand our rights, he refers to us as being instigators, animals and thugs. Nevertheless, we will continue to seek our rights.”

Workers at Abul Enein’s factories are also demanding improved health insurance and healthcare services, and workplace-hazard compensation. Standing under the hot sun outside the presidential palace, Omar Bahtimy — a production-line worker at the 10th of Ramadan City factory — said more than 950 workers at the two companies suffer from work-related ailments.

Two workers reportedly died in industrial accidents over the past decade, while about 10 are said to have lost fingers. Furthermore, Bahtimy and many other workers said the element zirconium — used in the production of ceramics — often contains radioactive impurities that could lead to cancer.

“Workers, especially those in production, suffer from numerous health problems, including respiratory illnesses from the dusts we inhale, along with spinal ailments from carrying heavy loads and operating heavy machinery,” Bahtimy said