For years, anecdotal reports had been filtering out of the Gebel Elba Protectorate that its ancient population of dragon trees was in decline. Though the dragon tree in Socotra — Dracaena cinnabari — had been exhaustively studied by the University of Edinburgh, relatively little was known about Egypt's Gebel Elba dragon tree — the Dracaena ombet.

But the motley collection of reports from rangers and botanists all agreed that a strange thing was happening: The trees were not regenerating. Few of the trees were younger than 30 years old, many were over 100 years old. Causes were debated — the 20-year drought, ravaging goats, tree-felling. One thing was clear: if the species did not regenerate, it would soon be extinct.

The D. ombet was already on the International Union for Conservation of Nature red list of threatened species. It was pegged as "endangered" — just three steps from being extinct. The next two steps would be "critically endangered" and then "extinct in the wild."

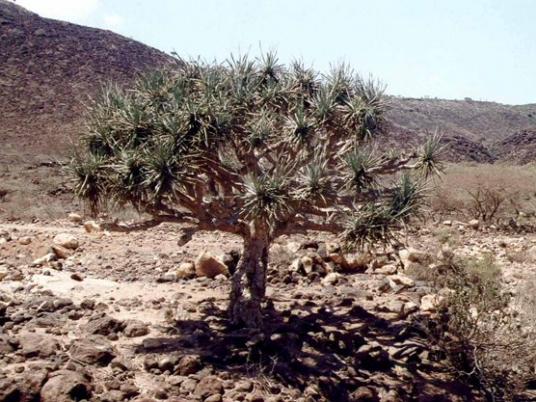

Growing up to 10 meters high, with long spiky leaves and a dense symmetrical umbrella canopy, the arborescent Dracaena has an otherworldly, Jurassic-type appearance. The wood is loose and fibrous and unsuitable for building or charcoal — a fact that has probably helped it survive to the present day. The trunk does not grow in rings, and alternative ways of determining specific trees’ ages by counting branches have come to naught. Some trees are thought to be 1,000 years old.

It is said to have an elusive taxonomy, with controversy among botanists about its exact classification. Thought to have once been widespread through North Africa, now tiny relict populations survive on high mountain sides, steep cliffs out of reach of ravaging goats and far-flung islands.

On the island of Socotra, off the coast of Yemen, the trunks of D. cinnabari are slashed in a cross-hatching pattern to harvest sap. Handfuls of the blood red crystal known as "dragons blood" retail at the market in Socotra's capital Hadibo for US dollars. In ancient Rome, Socotran dragon's blood was used as in alchemy, while statesman Pliny the Elder wrote it was produced by the mingling of blood from a battle between an elephant and a dragon. Though its applications have declined as alchemy has gone out of favour, the makers of Stradivarius violins retain its use as wood varnish.

D. Ombet grows outside of Egypt — in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia and Somalia — but the Gebel Elba protectorate has the largest population clusters. Just across the border in Sudan they have become extinct. In 1955, the Egyptian professor Mohammed Kassas visited the Erkowit district, in northern Sudan, and transplanted one tree to the Khartoum Botanic Garden. It was still alive in 1974 — by which time the remainder in Sudan had vanished.

Gebel Elba’s micro-climate is not found elsewhere in Egypt. Evaporation from the sea condenses on the summit as dew or mist, shrouding the mountaintop and condensing in rivulets. Though average rainfall in the region is less than 50mm, orographic precipitation (that is, precipitation caused by mountains) is as high as 400mm. The result is a rainforest — on the seaward face of the mountain. The other face is desert.

Though it is the largest of Egypt’s protectorates — some 35,600 square kilometers portioned off by prime ministerial decree in 1986 — travel to this area is exceedingly difficult. It is both too far from Cairo and too close to the Sudanese border for mass tourism. Entry requires a military permit. In fact, a long-running border dispute would have the protectorate in Sudan.

The remote location and twilight zone diplomatic status have probably helped the D. Ombet’s conservation. But it has been a passive kind of conservation — the active work of counting trees, educating the local Beja and Beshari tribes in conservation, building enclosures for seedlings, and so on, have been frustrated by distance from the capital. The lack of news from the region also creates a false sense of calm — it belies the area’s drying climate and changing socio-economic mix.

The border dispute with Sudan has created an incentive to develop the Egyptian border towns of Shalatein, Abo Ramad and Halaib. They’re growing quickly. In turn, this has put pressure on the tribespeople to adopt mainstream Egyptian culture. The population increase has also put pressure on D. Ombet’s habitat.

Marwan El Azzouni, a botanist by hobby, was one of the first to raise the red flag of warning. Between 1995 and 2002 he travelled extensively in the all but inaccessible protectorate, documenting the diverse and largely endemic flora. He is one of the few people who have succeeded in propagating D. Ombet seedlings.

Finally in October 2003, frustrated by apathetic conservation efforts, he proposed in an article for the magazine Plant Talk a survey of the D. Ombet population.

Four years later a team of eight protectorate rangers and community guides, assisted by a US$10,500 grant from the Conservation Leadership Program, conducted the first ever survey of the species.

“The species faces a rapid decline in its habitat's quality and population size. It seems likely that a major cause of the decline in extent and quality of Dracaena woodland is … the very gradual drying of the area of south Egypt.”

In total, the survey counted 383 trees, with “very low signs of regeneration”, due mainly to marauding goats chomping seedlings. “There is urgent need to promote and support a community-based conservation initiative in Gebel Elba for conserving the dracaena ombet and its critical habitats.”

In 2012 a road connecting Egypt to Sudan — the first land link between the countries — is due to be opened. It will run along the coast and directly alongside the protectorate. The mist oasis’s spell of seclusion will be broken. The D. Ombet would not be the first species in the protectorate to become extinct. The Egyptian ostrich was hunted to extinction just a century ago — you can still find the egg shells in the desert.