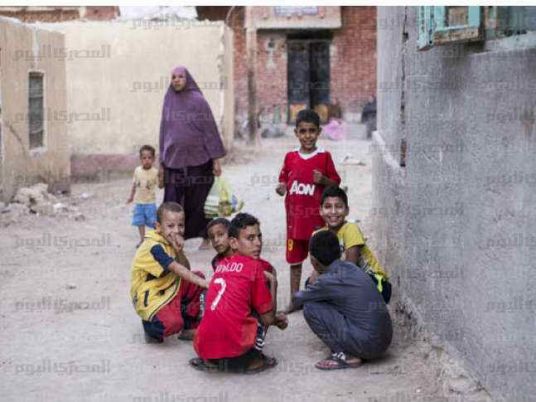

It was the circumstances in which they grew up that denied them education. Unlike their peers, and crippled by poverty since birth, the people of Abaadiya, a village at the far west of Fayoum, are unable to enjoy neither education nor medical care.

Living contiguously in unfinished brickstone houses, where some chambers are either without a ceiling or roofed with palm trunks and bamboo, the people of Abaadiya have their sons either denied education from the earliest stages, or dropped out from elementary school for incapability to afford the costs.

In a narrow alley of no more than 1.5 meter of width, and inside a house that looks more like a tomb, lives the family of Mohamed Ali Ibrahim. One bedroom and a living room with bamboos drooping from the ceiling, furniture composed of worn-out straw mats and shabby pots, children laying on the floor at bedtime is the scene at the home of Ibrahim, a casual stonecutter at the mountains of Youssef al-Seddiq region.

Ibrahim has failed to afford education for his children, according to his wife, Salwa Diab. He does not receive enough income to feed his kids: Abdullah, 14, Ramadan, 10, and Ahmed, 6. The family's poverty has obliged his oldest son to drop out of elementary school and join his father’s craft. Too young to endure the difficulty, he had no other choice to help secure his family’s expenses and spare it hunger.

Abdallah believes education is useless. He argues that many of his village peers who hold higher and lower educational certificates failed to get relevant jobs. “We live in bad conditions and we can’t afford food at many times. Schools require money for textbooks and tutoring,” he says. “My father is a humble wage earner, he should either feed my brothers or spend on our education.”

“Where should we get the money [for education] while we do not even eat regular meals?” Mrs Ibrahim says, adding that her husband does not work regularly. “People like us do not get education, it will neither feed our children nor cure our diseases.”

Her conviction that education is futile has made her disregard the idea of continuing with literacy courses which, she stressed, she attended as a compliment to a neighbor teacher.

Though this is the case with many families here, they are not as hard as Ahmed Elwany’s family. Mr Elwany, also a stonecutter, who retired due to his ailing health, lives with his wife and seven kids in a roofless, brickstone house of a single room where they are all crammed at bedtime to lay on shabby straw mat.

No one in this family has never received any kind of education, also due to financial incapacity.

Elwany says he has seven kids, the oldest of whom is 17. He says his youngest daughter is mentally and physically challenged, adding that he gave up and accepted the reality after he failed to spend on commutes to government hospitals for her treatment. Elwany says that at times, he and his family would give up food to spare expenses for his travels to Cairo to treat his girl at Abul Rish hospital. All ended up in vain when he was told that his daughter needed a brain surgery to cure atrophy, as diagnosed by the doctors.

“People like us do not know education, if we cannot treat our daughter, how can we spend on education?” says Elwany, whose ailing health shifted his hopes to his oldest son who could work in his same profession.

His wife, Dalal Ali, says her only hope is that, sympathizers would contribute to her daughter's treatment. “We do not need anything in the world but a surgery for the handicapped girl,” she pleads.

Elwany’s oldest daughter, Heba, like the rest of her brothers and sisters, believes education is fruitless. “Our life is different from more superior communities. We only hope we could find something to eat and a treatment for the sick. Education is for people who have the money,” she contends.

Edited translation from Al-Masry Al-Youm