Two years ago, organizers of the Cairo International Film Festival were determined to get their hands on the highly anticipated Egyptian film “Al-Mosafer” (The Traveller). The film had just been completed, and the organizers knew that including it in their lineup would not only boost their festival’s fading reputation, but also generate a good amount of attention. There were countless fights, arguments, and desperate phone calls, in an attempt to find a loophole in the film’s contractual restrictions, which stated that “Al-Mosafer” was to be screened at several foreign festivals before its Egyptian premiere. Finally, the matter was settled when one of the festival's organizers, a highly regarded film critic, came to the office and announced, “forget about ‘Al-Mosafer.’ I’ve just seen it, and it’s garbage.” Except, he didn’t use the word “garbage.”

At the time, I thought his reaction was just sour grapes. As it turns out though, he was being fair, and maybe even a little kind.

If “Al-Mosafer” were to be described in one word, it would be infuriating. Consider its backstory; after 38 years of doing absolutely nothing to support independent filmmakers, the Culture Ministry announced it would provide funding for a number of projects, based on the strength of submitted scripts. Somewhere along the line, the ministry narrowed down its list to a single candidate, and, inexplicably, decided to hand a staggering LE 10 million to an unknown director who had never actually made a feature film before. “Al-Mosafer’s” script then went on to win another LE 5 million from the state and, more importantly, secured its lead, Omar Sharif, the only Egyptian actor so far to gain widespread international acclaim.

After seven months filming, a year of editing, and countless ominous accounts of production and distribution difficulties, how has this revival of state-sponsored filmmaking been revealed to the public? By being released in a paltry four movie theatres, with no significant advertising or marketing campaigns to support it, two weeks after most Egyptians had their fill of movies during the Eid film season, which is kind of appropriate, since, all things considered, “Al-Mosafer” is a bit of an embarrassment.

The biggest, and most obvious problem is the script; especially given how much praise and support it received. Director Ahmed Maher claims it took him four years to write “Al-Mosafer,” which begs the question: why? With its relatively simple story chronicling three supposedly significant days in one man’s life, “Al-Mosafer” has a minimal cast portraying one-dimensional characters, and plot complications that are not really complicated at all. There is not a single line of memorable dialogue and the protagonist’s motivations remain vague, if not entirely implausible. In the first of the film’s three segments, Hassan commits a terrible crime, yet the reasons why are never made clear, and his lack of remorse is disconcerting, making it impossible to empathize with him. The supporting characters are equally difficult to relate to, their roles dictated more by the needs of a naïve script than any sense of realism.

The acting is a less offensive kind of bad, in that it’s unintentionally hilarious. Portraying Hassan in the film’s first two segments, Khaled al-Nabawy’s bewildering performance is a mixture of a bad impression of Omar Sharif, and a slightly better impression of a cat. One minute he is making threats and casting angry glares, the next he is pawing the air and cooing in a soft-spoken, child-molester voice. It always seems as if he’s one step away from either attacking someone, or rubbing up against them. The middle segment’s porn stache doesn’t help, either. As Hassan’s love interest, and then potential daughter (and love interest), Cyrine Abdel Nour, who desperately tries to emulate Egyptian starlets of the 1940s and 1950s, is even more laugh-out-loud awful, no matter which incarnation of her character she is playing. Every close-up of her struggling to emote (and there are many) plays like a parody, and the scene where she reacts to seeing a relative’s body in the morgue will leave you wondering how bad the other takes had to have been for the director to settle for this one.

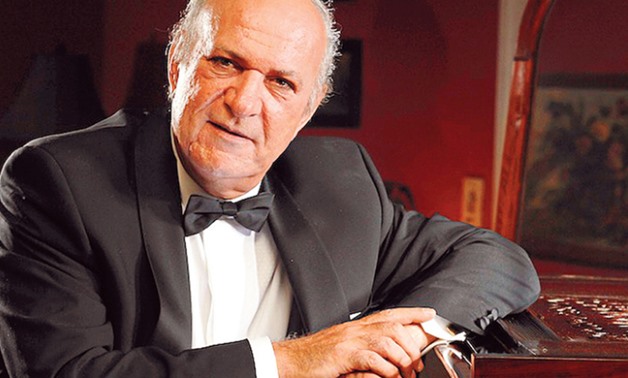

Despite being the biggest name in the film and the only face on the poster, Omar Sharif does not appear until “Al-Mosafer’s” final segment, which, unsurprisingly, is the best of the three. It is not that Sharif’s acting is great; it is just that by this point, you’re likely to have had more than you can handle of Nabawy’s whacked-out performance. The segment’s strength, rather, comes from the film’s youngest cast member, Sherif Ramzy – the only person onscreen not guilty of overacting – and an improvement in writing over the first two-thirds. Whereas the earlier episodes of “Al-Mosafer” are flat, disengaging, and frustratingly slow, the final one has enough tone shifts and mildly amusing moments to revive the viewer’s interest, if only briefly. And even though the ending is an absolute mess – “Al-Mosafer” is one of those films that refuses to settle for a single denouement and keeps fading back in every time you expect the credits to start rolling – at least it breaks the monotony of the 100 minutes leading up to it by attempting to shed some light on Hassan’s internal struggle.

While there is something to be said about a first-time director taking on a film of this scale, “Al-Mosafer” has enough shortcomings to suggest Maher’s aim has far exceeded his current ability as a filmmaker. There are hints of depth, but they’re buried under Maher’s self-indulgent script and directing, making it unclear whether the film is meant to be a character study, a parable, or an example of old-fashioned storytelling. In terms of technique, everything is staged to the point of artificiality. From the placement and movement of the extras, to the spotless sets and creaseless costumes -it’s all very pretty, but never authentic. Too often, “Al-Mosafer” feels like an elaborately produced theatrical play, filmed for a cinematic release.

The film also suffers from excessive stylistic flourishes that end up interrupting rather than enhancing the flow of events. In the first segment of “Al-Mosafer,” fade-ins are used to an absurd degree, often several times in the same scene. This is not done for any legitimate editing purposes – witness one of the most unconvincing shot transitions of all time when, later in the film, a minor character raises his shovel to excavate a grave.

Worst of all, though, is how “Al-Mosafer” is being touted as an example of “arthouse” cinema, and a return to “intellectual” filmmaking. Neither statement could be further from the truth. For starters, “independent” films and “art” films generally do not have large budgets, whereas “Al-Mosafer” is one of the most expensive productions in the history of Egyptian cinema, starring one of the most popular actors in the Arab world. In this context, “independent” means not produced by a major studio, as opposed to being funded by the filmmaking team.

Secondly, just because a film revolves around real people living in the real world does not mean it’s intellectual. That’s only what the “El-Limby” film series wants you to believe. It would be wrong to say “Al-Mosafer” is not a mainstream film; there’s not a single person onscreen who is not a star, or at least, a familiar face, and, while it may not cater to the lowest common denominator, there’s nothing remotely alienating about its story, or the manner in which it is told. It would also be unfair to blame “Al-Mosafer’s” inevitable financial failure on the claim that audiences “did not get it,” mainly because there’s nothing to get. The film echoes its main character in that both are empty vessels, underdeveloped and driven by questionable motives and a misguided sense of self-importance.

On the plus side, there are a few instances in “Al-Mosafer” that suggest film censors are reconsidering their policies. Whether or not this will extend to films not produced by the Ministry of Culture, though, remains to be seen.

Ultimately, it is difficult to see Maher’s debut as anything but a wasted opportunity. It may be an exaggeration to say “Al-Mosafer” could have heralded a new age of filmmaking in Egypt, built on the work of younger auteurs untainted by the financially-motivated obligations of a corrupt studio system – but it certainly could have brought us closer. As it is, “The Traveller” takes a long journey in the wrong direction.