Greeks voted on Sunday whether to accept or reject the tough terms of an aid offer to stave off financial collapse, in a referendum that may determine their future in Europe’s common currency.

Held against a backdrop of default, shuttered banks and threats of financial apocalypse, the vote was too close to call and looked certain to herald yet more turbulence whichever way it went.

The country of 11 million people is deeply divided over whether to accept an offer by international creditors that left-wing Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, elected in January on a promise to end years of crippling austerity, calls a “humiliation”.

He is urging a resounding ‘No’, saying it would give him a strengthened mandate to return to negotiations and demand a better deal, including a writedown on Greece’s massive debt.

His European partners, however, say rejection would set Greece on a path out of the euro, with potentially far-reaching consequences for the global economy and Europe’s grand project of an unbreakable union.

"I voted 'No' to the 'Yes' that our European partners insist I choose," said Eleni Deligainni, 43, in Athens. "I have been jobless for nearly four years and was telling myself to be patient … but we've had enough deprivation and unemployment."

Voting on whether to accept more taxes and pension cuts would be divisive in any nation at the best of times.

In Greece, the choice is faced by an angry and exhausted population who, after five years of pension cuts, falling salaries and rising taxes, have now suffered through a week of capital controls imposed to prevent the collapse of the nation's financial system.

Pensioners besieging bank gates to claim their retirement benefits, only to leave empty-handed and in tears, have become a symbol of the nation's dramatic fall over the past decade, from the heady days of the 2004 Athens Olympics to the ignominy of bankruptcy and bailout.

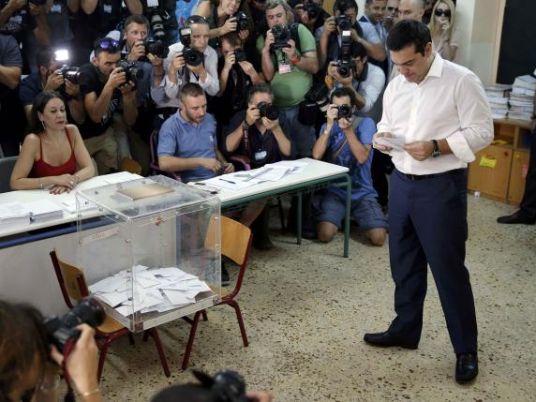

Tsipras, a 40-year-old former student activist, has framed the referendum as a matter of national dignity and the future course of Europe.

“As of tomorrow we will have opened a new road for all the peoples of Europe,” he said after voting in Athens, “a road that leads back to the founding values of democracy and solidarity in Europe.”

A ‘No’ vote, he said, “will send a message of determination, not only to stay in Europe but to live with dignity in Europe.”

Not everyone agreed.

“Dignity”

“You call this dignity, to stand in line at teller machines for a few euros?” asked pensioner Yannis Kontis, 76, after voting in the capital. “I voted 'Yes' so we can stay with Europe.”

Polls close at 7 pm (1600 GMT), with the first official projection of the result expected at 9 pm.

Four opinion polls published on Friday showed the 'Yes' vote marginally ahead. A fifth put the 'No' camp 0.5 percentage points in front. All were well within the margin of error.

Called at eight days’ notice, the referendum offers Greece a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ vote on a proposal that is no longer on the table.

Given the chaos of the past week, in which Greece became the first developed economy to default on a loan to the International Monetary Fund, a new bailout package would probably entail harsher terms than those on offer even last week.

Anxious Greeks rallying for a 'Yes' vote also say Greece has been handed a raw deal but that the alternative, a collapse of the banks and a return of the old drachma currency, would be far worse.

The ‘No’ camp says Greece cannot afford more of the austerity that has left one in four without a job.

If Greeks vote 'Yes' to the bailout, the government has indicated it will resign — triggering a new chapter of uncertainty as political parties try to cobble together a national unity government to keep talks with lenders going until elections are held.

European creditors have said a 'Yes' vote will resurrect hopes of aid to Greece. A ‘No’, they say, will represent rejection of the rules that bind the eurozone nations, leaving Greece to fend for itself.

“If they (Greeks) say ‘No’, they will have to introduce another currency after the referendum because the euro is not available as a means of payment," Martin Schulz, the president of the European Parliament, said in remarks broadcast on Germany’s Deutschlandfunk radio on Sunday.

"And how are they going to pay salaries? How are they going to pay pensions? As soon as someone introduces a new currency, they exit the eurozone.”

Much will depend on the European Central Bank, which on Monday morning will review its emergency liquidity line to Greek banks, keeping them afloat.

The ECB could decide to freeze the liquidity or cut it off altogether if Greeks vote ‘No’, or if Athens subsequently defaults on a bond redemption to the ECB on July 20.

An inconclusive result may sow further confusion, with the potential for violent protests.

"The nightmare result would be 51-49 percent in either direction," a senior German official said. "And the chances of this are not insignificant."