As Cairo braces for yet another hot, sweaty summer, experts say our efforts to stay cool are actually making the city hotter, creating an “urban heat island.”

Cairo’s lack of green spaces, its traditional construction materials, and its un-shaded pavements and rooftops create the phenomenon of a city that has markedly warmer temperatures than surrounding regions.

Roofs and pavements absorb more than 80 percent of the sunlight that hits them. This energy is converted to heat, which results in hotter, more polluted cities and higher energy costs, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

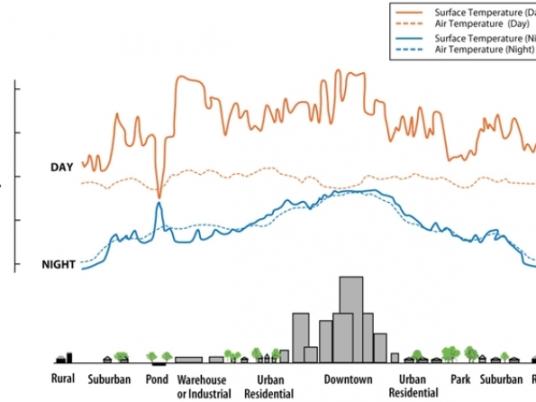

The annual mean air temperature of a city with a million people or more can be 1 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than its surroundings. In the evening, the difference can be as high as 12 degrees. More than making you uncomfortable, this rise in temperature brings more air pollution, increased energy usage and larger numbers of respiratory issues, exhaustion and heat stroke.

Heat islands can also exacerbate the impact of heat waves, leaving children, the elderly and those with existing health conditions at particular risk.

With the average summer temperature hovering in the mid-30s in Cairo, experts say this phenomenon can lead to some serious heat.

According to Ayman S. Mosallam, the founder of the Egyptian Green Building Council, more can be done to combat rising temperatures.

“Urban heat islands are something we can solve, and green-building practices and contractors in New York and elsewhere have had a lot of success,” he said.

While Egypt is stuck with its arid climate, geography and desert topography, there is a range of energy-saving strategies that can be easy built into the development of a city — from increasing vegetation, to landscaping, to building parks or changing building and road materials.

On an individual level, people can plant trees, vegetation and rooftop gardens; reduce cooling energy use, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions; and clean the air and reduce noise levels, according to the EPA.

Even slightly reducing the reliance on air conditioners, which tax electrical grids with energy demands, can go a long way, says urban planner Amir Gohar. Air-conditioning systems release waste heat into the atmosphere, and their widespread use can inadvertently elevate city air temperatures

“We need to raise people’s awareness that keeping your AC at 16 degrees is actually making the air hotter outside,” he said, adding, “People need to have a feeling of belonging to the outdoors and public space, they need to have a sense of ownership.”

Construction materials also contribute to the urban heat island effect in Egypt, says Mosallam. The bricks and concrete commonly used in construction projects here soak up solar radiation, convert it into heat and transmit it into the air above them.

“The darker the material, the more energy it’s going to absorb,” says Mosallam. EPA studies have shown that conventional rooftops and sidewalks can be 28 to 50 degrees hotter than the surrounding air.

Green energy advocates say highly reflective materials that minimize the amount of light converted into heat can help drop temperatures inside buildings considerably. Adding a coat of white paint to a roof can make it 28 to 36 degrees cooler than dark roofs, while even aged white roofs are up to 28 degrees cooler, according to the Heat Island Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the US.

Cool roofs can lower the use of air conditioners, thus lowering electricity demand and air pollution and increasing a roof's lifetime, says Mosallam.

While a single cool roof benefits building owners and occupants by reducing temperature and energy demands, installing cool roofs throughout a community can reduce the overall air temperature in the area.

“It makes a big difference if the color of the surface or the amount that is exposed and absorbs heat is less or lighter, and that’s with roofs and pavements,” says Gohar.

Conventional paving materials can reach peak summertime temperatures of 20 to 30 degrees hotter than Cairo’s average temperature. But there are many paving options that are lighter in color and create more reflective surfaces. Depending on the technology used, cool pavements can improve storm water management and water quality, increase surface durability, enhance nighttime illumination and reduce noise.

For Gohar, a more practical solution for Egypt would be simply to shade the streets better.

“It’s not necessary to build narrow roads, but instead plant some trees and rely more on public transportation to reduce pollution,” Gohar says.

To cool large cities, developers and architects must rethink their building strategy.

“There are several practices [to lower temperatures], but it’s a byproduct to development,” says Gohar.

While green building practices remain slow to take root in Egypt, development projects from Rio de Janeiro to India have already begun tackling the heat with great success.

Recent research by Columbia University in the US showed that rooftop surface temperatures in New York were reduced by as much as 24 C when tar and asphalt were replaced with a permanent white polymer coating.

In Egypt, Gohar says, there is little political will. He stresses the importance of individual responsibility within the development field.

“There is no political support for changing construction materials, but that’s the kind of efforts intellectuals should be making. Those working in the field should stop doing business as usual. Architects should push for it and refuse projects that are not green,” Gohar says.