As the Islamic holy month of Ramadan begins, Habiba says she is “terrified” by the thought of fasting this year.

After her disordered eating patterns spiraled into bulimia and binge eating disorder during her mid-teens, she says the ritual of abstaining from food and drink from sunrise to sunset can exacerbate the need to restrict her eating further and risk slipping into a toxic cycle.

But making the decision to refrain from the practice feels like she is neglecting a key part of her faith, she says.

“I don’t trust myself with keeping a fast because I know … I’ll start to enjoy the feelings of hunger and I’m terrified (of) what that will do to me,” said the 30-year-old UK-based Muslim editor, who asked CNN to use only her first name for privacy reasons. “I do feel sad. I feel like I’m missing out on a really spiritual experience.”

Habiba was nine years old when she first had the urge to make herself sick, she says. By the age of about 16 she says she was skipping meals, tracking calories, blacking out as a result of hunger, overexercising and vomiting at least 15 times a day.

“I would never wish something like bulimia, especially, on anyone, because it’s like an addiction.”

Habiba is not alone in her experience. A growing number of Muslim doctors and psychologists are trying to bridge the gap between faith leaders and worshippers like Habiba, who say they face marginalization when trying to access support within their own communities, as well as in the public health system.

“Minorities are underrepresented. It’s not that they don’t have eating disorders or suffer, but there is all this stigma around who comes to get help,” Dr. Omara Naseem, a UK-based counseling psychologist who specializes in treating eating disorders, said. These are “invisible and indiscriminate” illnesses that transcend age, religion, gender and sexuality, she added.

“It’s an act of worship to take care of your body and health. Therefore, go and get the right help that you need,” she said.

Creating a ‘binge purge cycle’

During Ramadan, Muslims are encouraged to hydrate and eat a balanced meal before sunrise and then break their fast with a date and water at sunset, followed by a larger meal. Worshippers also engage in other forms of practice including increased prayer, giving more to charity, volunteering and participating in communal meals.

However, the act of fasting during daylight hours can mask restrictive dieting patterns associated with eating disorders, said Naseem. Exercising control and experiencing hunger while fasting could generate a desire to binge large amounts of food quickly at iftar – the breaking of the fast after sundown – which could result in feeling out of control and “ashamed,” creating a “binge purge cycle” and setting back recovery, she added.

According to the Quran, people who are sick or traveling are not required to fast as long as they make up fasts once they are healthy or feed less fortunate Muslims throughout the month.

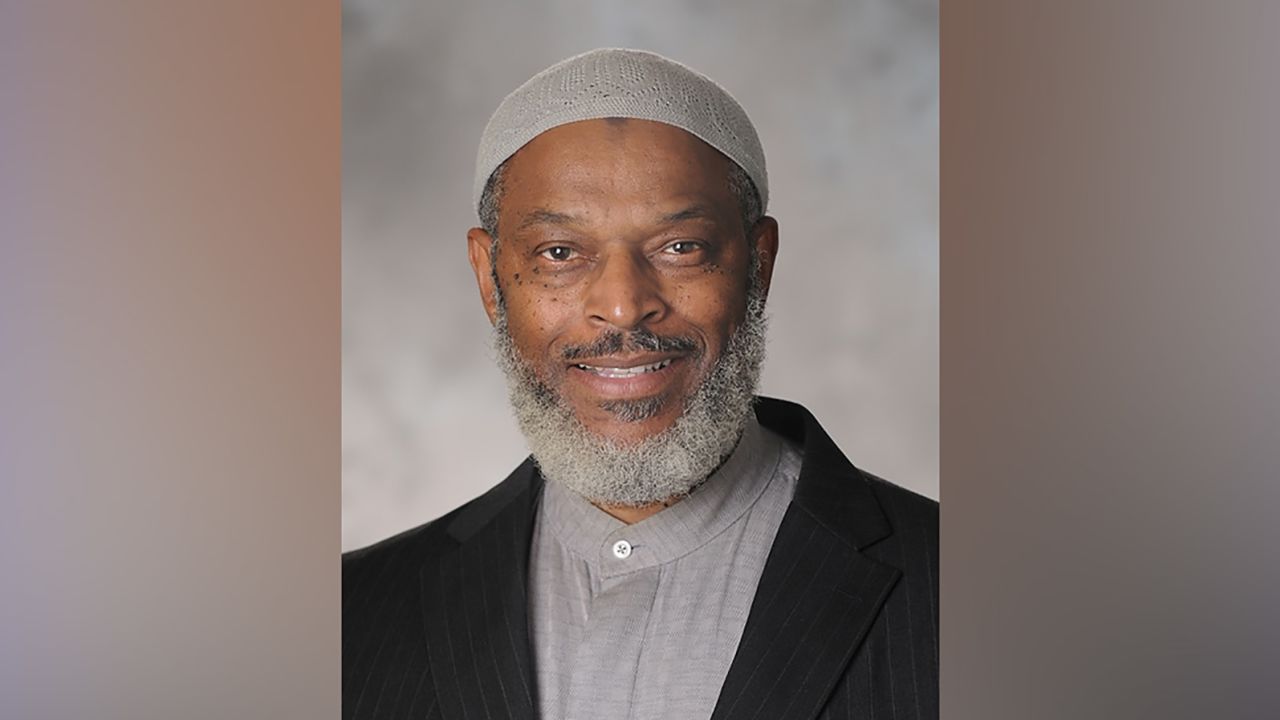

Therefore, if someone has an illness or condition that is verified by a medical professional, they are not required to fast, said Imam Nadim Ali, a Muslim faith leader and licensed professional counselor based in Atlanta, Georgia.

For example, children and the elderly and people who are pregnant, menstruating, or require daily medication are exempt from fasting.

However, community and society-wide taboos mean that mental health illnesses are not given credence in the same way as physical sickness, both Naseem and Ali said. That means those who choose not to fast due to mental health illnesses face “guilt and shame” from their communities and wider society, added Naseem.

Cultural barriers

Habiba said she has childhood memories of having her body constantly audited by members of her extended family, a behavior she says is symptomatic of the cultural pressures some South Asian and Muslim girls face as they enter womanhood.

When she was 15, she remembers an uncle telling her she’d “gotten fat” after returning from a family trip to Turkey. “Comments like that stick forever,” she said. Over the following years, her weight dropped drastically.

At the same time, she remembers being told by extended family members that she could no longer play outside and skateboard with her boy cousins. Instead, she was encouraged to hang out with her girl peers and play with makeup.

Despite having “liberal” parents, she said, she believes her eating disorder was partly a response to the pressure of fitting into strict gender roles assigned by her community and wider society.

When she was about 16, Habiba said her eating disorder symptoms worsened until her parents took her to a local doctor. She received outpatient psychiatric care at a children’s mental health unit until she was 18, when she was transferred to an adult mental health unit.

However, she says the cultural differences between herself and the White therapists she saw meant they could not understand the nuanced pressures she faced as a woman in her community; and how they were intrinsically tied to her eating disorder.

“I had White therapists who just did not understand and would really just be very condescending about, you know, things that I wanted to talk about or things I was struggling with.”

Farheen Hasan, a 27-year-old research psychologist based in Bristol, southwest England, agrees that there’s a need for therapists to understand specific cultural pressures.

At the age of 18, Hasan said she started to exhibit disordered eating patterns in the form of avoiding food, over-exercising and becoming obsessed with healthy eating. Every year, she said she faced an internal struggle over whether or not to fast during Ramadan.

“I think we need access to therapists who understand our culture, religion and struggle – and who can provide professional guidance and support,” she told CNN over email.

Getting help

Habiba and Hasan’s stories reflect the systemic challenges people from underserved communities widely face when accessing mental health support.

Even though people of color have higher rates of some mental health disorders than White people, they face greater disparities in getting help due to institutional discrimination and interpersonal racism and stigma. Black, indigenous and people of color are significantly less likely than White people to have been asked by a doctor about eating disorder symptoms, and are half as likely to be diagnosed or to receive treatment, according to a report by the US National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders.

Halima Eid, a licensed professional clinical counselor and co-founder of AMALY, a California-based non-profit organization that aims to challenge the stigma around mental health in Muslim communities, said it can be hard for people in those spaces to access the information they need.

Eid established AMALY in 2020 to offer accessible therapy services, workshops, support groups and educational talks that are tailored to her local Muslim community in San Diego, California. She also offers services online that extend to Muslims globally.

Last spring, she set up a virtual support group to help Muslims with eating disorders as they navigate Ramadan. She said that after the screening process about 30 people initially registered across two cohorts, including Muslims from the US, Australia and the UK. She intends to run the same group this year.

“It is a very lonely experience to suffer from any disease or disorder on your own,” she said. “Then there’s the guilt that they’re not pleasing Allah and they’re not being good Muslims. So, we challenge perfectionism in Islam, perfectionism as Muslims during Ramadan, because a lot of people struggle.”

Both Eid and Naseem, the UK-based counseling psychologist, use their Islamic and medical knowledge to serve Muslims that seek support from mental health professionals, who have a similar lived experience as women who practice Islam.

“I can offer a unique perspective … it helps you use your skill set for good to groups that maybe wouldn’t engage or wouldn’t feel comfortable speaking to somebody who isn’t from their background,” said Naseem, who has created a Ramadan guide offering nutrition and faith-based advice for Muslims with eating disorders.

Breaking a cycle of shame

Habiba says her bulimia reached a turning point several years ago, when she returned home from a friend’s baby shower and made herself sick after eating cakes and sweet treats.

“I remember just looking at my body and being like, I don’t like this. I don’t like the way that I look and I don’t think I’m ever going to love myself, but I think I just need to accept it,” she said. “I don’t know if I can ever say that I’m fully recovered. I know that I still have that voice … in my head. But it’s quieter now.”

Now, she said she is able to keep her eating disorder at bay by identifying her triggers and forcing herself to eat when she is drawn towards restrictive dieting patterns.

Ramadan and Eid celebrations can trigger her eating disorder, she said, because she experienced pressure to eat large amounts of food at iftar, and received judgmental comments from family members who might not understand her decision not to fast.

Hasan, the Bristol-based research psychologist, said Muslims in their position need “social acceptance” from community leaders.

“A lot of stress and mental toll would be reduced if we had acceptance and acknowledgment in the community that people struggle in different ways, and we should understand and accept them, instead of stigmatising them,” she said.

Habiba said she still misses the communal aspect of breaking fasts during Ramadan, attending family dinners and counting down the days until Eid al-Fitr, the festivities that mark the end of Ramadan.

“I do feel like I’m left out of the club,” Habiba said, adding that she hopes she’ll get to a point in the future where she can fast again and be sure that her faith, rather than a desire to restrict her calorie intake, is her motivation.

Ali, the Atlanta-based Imam and counselor, suggested ways that Muslims with eating disorders can engage with the holy month aside from fasting, including reading the Quran, attending nightly taraweeh prayers, and donating to a feeding program.

He said faith leaders and family members should acknowledge the challenges Muslims with mental health struggles face during Ramadan, and offer them guidance to help break the intergenerational cycle of shame and guilt that exists across society.

“Islam is a religion that does not want people to jeopardize their lives to engage in forms of worship,” he said. “I think the important thing is for us religious leaders to be able to show empathy to the least among us, the most vulnerable among us.”

CNN’s Kristen Rogers contributed reporting.