While trials of former regime officials may seem like a positive step in the fight against corruption, Ashraf Ali al-Baroudy, the president of the High Court of Appeals, still has a concern: those government figures are in jail due to a popular uprising and an effective oversight and anti-corruption system in the government had little to do with their arrests.

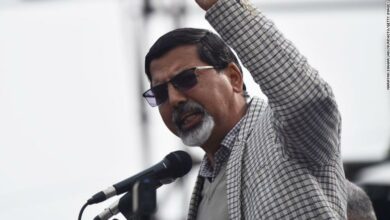

“Do we need to remove regimes for the public prosecutor and the Illicit Gains Authority to do their work?” Baroudi said, during the release of a Transparency International report on legislation in Egypt and its compliance with the UN Convention against Corruption, of which he was the lead author.

Even after 25 January, anti-corruption advocates say that there is still no transparent system of accountability that would enable oversight agencies to work free from interference from former officials, the current interim cabinet or the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

“Transparency remains a key problem in the administration of either information or processes or decisions in Egypt. It harms [the ability to] regain trust in a government system and detaches citizens from the different policies and agencies,” Middle East and North Africa Program Coordinator for Transparency International Omnia Hussein told Al-Masry Al-Youm.

Egypt boasts a number of oversight and monitoring entities, such as the Central Auditing Organization (CAO), Administrative Control Agency, Administrative Prosecution, Illicit Gains Authority, General Prosecution, Consumer Protection Agency and the General Administration for Investigation of Public Funds, which is part of the Ministry of Interior.

All these bodies are incapacitated because they are, for the most part, under the direct auspices of the executive branch, severely compromising their independence, credibility and effectiveness, anti-corruption advocates say. Additionally, they often have overlapping responsibilities.

“They have immense authority but little responsibility because they are not independent. They answer to the executive branch so they cannot implement anything that goes against the executive’s will,” said Ghada Moussa, the director of the Ministry of Administrative Development's Governance Center and secretary general of itsTransparency and Integrity Committee.

Baroudy told Al-Masry Al-Youm, “How can we have so many oversight bodies in Egypt but in spite of that we have so much corruption? That is because these entities are answerable to the Egyptian government, instead of monitoring [it].

“The Illicit Gains Authority is part of the Ministry of Justice, so [it] answers to the minister, who answers to the prime minister, so how can this body hold the boss of its boss accountable for anything?” he asked. “If entities that are responsible for protecting citizen rights lose their independence, they lose people’s trust, and revolutions happen.”

This is echoed in the Transparency International report, which states that the affiliation of all monitoring bodies to the executive branch has a negative effect on their independence because the branch that is subject to their oversight also oversees them.

However, Ahmed al-Sandayuny, an auditor with the Illicit Gains Authority and member of Monitors Against Corruption told Al-Masry Al-Youm that a distinction needs to be made between the numerous oversight bodies.

“The only true oversight agency in Egypt is the CAO, because it is constantly monitoring,” he said. “The others are investigative bodies answering to the executive branch, which are only mandated to work when something is referred to them.”

Sandayuny concurred with the lack of independence of the body and the influence of the executive branch. He said that the problem with the CAO is that the president appoints its head. Initially Law 144/1988 was meant to govern the process by stipulating the CAO head be chosen by a two-thirds majority in Parliament and the approval of the president.

The domination of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party in Parliament ensured the choice was always rubber-stamped. A decade after its inception, in 1998, the law was amended to become Law 157 and the clause requiring parliamentary approval removed.

Another challenge to governmental oversight under Mubarak's administration was a tendency to selectively apply recommendations. The same was often true of court rulings, such as a court order to halt gas exports to Israel until a controversial export deal could be reviewed, which was ignored by the government.

Hussein, of Transparency International, contends that political will is integral for doing away with selective implementation of legislation. Either the current anti-corruption agencies must be restructured to clearly delineate their mandates and assert their independence, or a new, fully independent commission must be created with a wide mandate, ample resources and a judicial police force to enforce its decisions, Hussein said.

“The non-implementation of judicial decisions is a catastrophe," Baroudy agrees. "Selectivity in carrying out court orders erodes the principle of law in the first place. And it makes people protect their rights with their own hands.”

Many consider police reform an essential prerequisite for fair law enforcement.

“Serious police reform has to be tackled immediately, on so many levels,” Hussein says. “They need to enforce the law and the rule of law in absolute terms, not selective terms related to the will of the executive branch. You also need internal reforms, enhancing accountability and transparency. There must be no tolerance for corruption.”