Iran has hand picked hundreds of trusted fighters from among the cadres of its most powerful militia allies in Iraq, forming smaller, elite and fiercely loyal factions in a shift away from relying on large groups with which it once exerted influence.

The new covert groups were trained last year in drone warfare, surveillance and online propaganda and answer directly to officers in Iran’s Quds Force, the arm of its Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) that controls its allied militia abroad.

They have been responsible for a series of increasingly sophisticated attacks against the United States and its allies, according to accounts by Iraqi security officials, militia commanders and Western diplomatic and military sources.

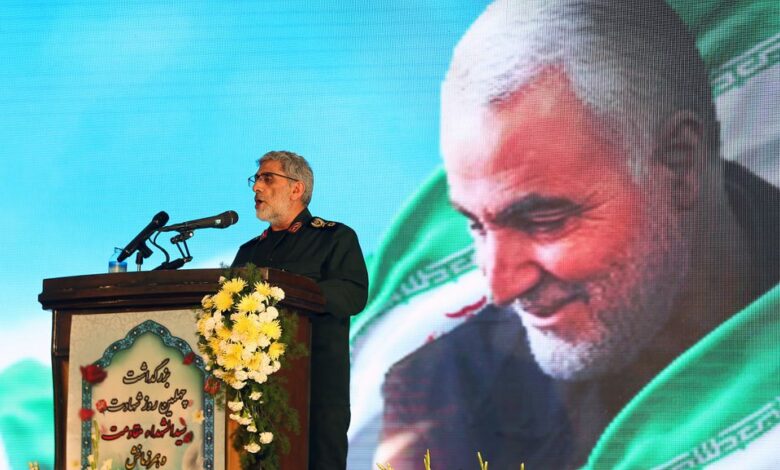

The tactic reflects Iran’s response to setbacks – above all the death of military mastermind and Quds Force chief Qassem Soleimani, who closely controlled Iraq’s Shi’ite militia until he was killed last year by a US drone missile strike.

His successor, Esmail Ghaani, was not as familiar with Iraq’s internal politics and never exerted the same influence over the militia as Soleimani.

Iraq’s large pro-Iran militia were also forced to adopt a lower profile after a public backlash led to huge mass demonstrations against Iranian influence in late 2019. They were hit by divisions after Soleimani’s death and seen by Iran as becoming harder to control.

But the shift to relying on smaller groups also brings tactical advantages. They are less prone to infiltration and could prove more effective in deploying the latest techniques Iran has developed to strike its foes, such as armed drones.

“The new factions are linked directly to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps,” an Iraqi security official said. “They take their orders from them, not from any Iraqi side.”

The account was confirmed by a second Iraqi security official, three commanders of larger, publicly active pro-Iranian militia groups, an Iraqi government official, a Western diplomat and a Western military source.

“The Iranians seem to have formed new groups of individuals chosen with great care to carry out attacks and maintain total secrecy,” one of the pro-Iran militia commanders said. “We don’t know who they are.”

The Iraqi security officials said at least 250 fighters had travelled to Lebanon over several months in 2020, where advisors from Iran’s IRGC and Lebanon’s Hezbollah militant group trained them to fly drones, fire rockets, plant bombs and publicise attacks on social media.

“The new groups work in secret and their leaders, who are unknown, answer directly to IRGC officers,” one of the Iraqi security officials said.

The Iraqi security officials and the Western sources said the new groups were behind attacks including against US-led forces at Iraq’s Ain al-Asad air base this month, Erbil International Airport in April and against Saudi Arabia in January, all using drones laden with explosives.

Those attacks caused no casualties but alarmed Western military officials for their sophistication.

Iranian officials and representatives of the Iraqi government, the pro-Iran militia and the US military did not reply to requests for comment on the record. The US Department of State said it was not able to comment.

BATTLE WITH WASHINGTON

Iran is the preeminent Shi’ite Muslim power in the Middle East, and its leverage over Iraq, the Arab world’s biggest Shi’ite-majority country, is one of the main ways it spreads its sway across the region.

It has been jockeying for influence in Iraq with the United States since US forces toppled Sunni Muslim dictator Saddam Hussein in 2003, empowering Iraq’s Shi’ites.

After Islamic State fighters swept into a third of Iraqi territory in 2014, Washington and Tehran found themselves on the same side, both helping the Shi’ite-led government defeat the Sunni Muslim militants over the next three years.

The United States, which had withdrawn from Iraq in 2011, sent thousands of troops back.

Iran, meanwhile, backed large militia groups such as Kataib Hezbollah, Kataib Sayyed al-Shuhada and Asaib Ahl al-Haqq, each able to deploy thousands of armed fighters and given quasi-official status to help fight Islamic State.

But after Soleimani’s death, and with protesters turning against groups publicly linked to Iran, officials in Tehran became suspicious of some of the militia they had promoted and grew less supportive, according to the militia commanders.

“They (Iran) believed leaks from one of the groups helped cause Soleimani’s death, and they saw divisions over personal interests and power among them,” said one.

Another said: “Meetings and communications between us and the Iranians have reduced. We no longer have regular meetings and they’ve stopped inviting us to Iran.”

The Iraqi security officials, a government official and the three militia commanders all said the Quds Force began splitting trusted operatives away from the main factions within months after Soleimani’s death.

The shift from supporting mass movements to relying on smaller, more tightly controlled cadres reflects a strategy Iran has pursued before: at the height of the US occupation of Iraq in 2005-2007, Tehran created cells that proved particularly effective at deploying sophisticated bombs to pierce US armour.

DIPLOMATIC REOPENING

Since President Joe Biden came to office, Tehran has reopened diplomatic channels with both Washington and Riyadh. One of its main sources of leverage in those talks is its power to strike its foes.

The drones its allies now use for attacks are far harder to defend against and detect than regular rocket fire, increasing the danger posed to the remaining 2,500 US troops in Iraq.

General Kenneth McKenzie, head of US Central Command, said in April after the Erbil attack that Iran had made “significant achievements” from its investment in drones.

Last year, previously unknown groups began issuing claims of responsibility following rocket and roadside bomb attacks. Western officials and academic reports often dismissed these new groups as facades for Kataib Hezbollah or other familiar militia. But the Iraqi sources said they are genuinely separate and operate independently.

“Under (Soleimani’s successor) Ghaani, they’re trying to create groups with a few hundred men from here and there, meant to be loyal only to the Quds Force, a new generation,” the Iraqi government official said.

___

IMAGE: Brigadier General Esmail Ghaani, the newly appointed commander of Iran’s Quds Force, reads the will of Major General Qassem Soleimani, who was killed in a US air strike at Baghdad Airport, during the forty day memorial at the Grand Mosalla in Tehran, Iran February 13, 2020.