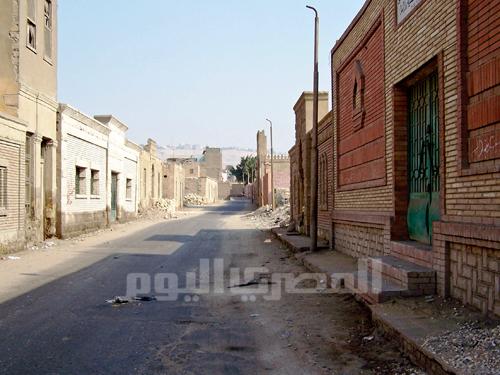

Qarafa al-Arafa, or the City of the Dead, a centuries-old Cairo necropolis, is one of a hundred slums defining the informality of the city’s urban panorama. The monumental patchwork of tombs and mausoleums spread at the foot of the Moqattam Hills offers a peculiar case of informal settlement in which the living cohabitate with the deceased.

Many stereotypes and misconceptions, often strengthened by the media, have marginalized this area from the formal metropolis, portraying its inhabitants as squatters with no respect for the area’s sanctity.

Since 2007, Liveinslums, an Italian NGO operating in informal settlements and critical areas of the Third and Fourth World’s great cities, has developed research projects in the City of the Dead to enhance its local resources, with the support of architects, anthropologists, agronomists and sociologists.

Two years ago, the NGO tested a micro garden project that officially kicked off last October. The two-year project aims at building micro gardens for 60 families of the neighborhood by October 2013, as well as offering vegetable gardening training for locals to ensure the sustainability of these gardens.

Among the tombs

According to UN-HABITAT, the United Nations housing agency, 70 percent of Cairo’s dwellings are informal settlements, a trend that started during the 1950s and 1960s after massive rural exoduses. The construction in desert areas promoted in the 1970s did not help solve the city’s housing problem.

The high population concentration in Cairo has led to the occupation of historic, abandoned districts such as the City of the Dead.

Government figures put the number of people who live among the tombs and mausoleums in the area at about 500,000 to 800,000, but the data the government provides on informal areas and their populations is often highly inaccurate and inconsistent.

Since the City of the Dead covers a wide area, Liveinslums — which had also previously worked on tourism-related projects in the area — concentrated its efforts on the northeastern section of the southern cemetery.

The members of the NGO work with the locals, joined by groups of experts such as architects and designers every three months. The latter help Liveinslums in the construction and designing processes for the transportable gardens during a 10-day intensive workshop.

The vegetable gardens are grown off-soil, and the technology used is mostly hydroponic culture, which uses mineral substrates with added nutrients to replace fertile soil.

“The ground layer is composed 70 percent of peat moss and 30 percent of perlite,” explains agronomist Carmen Maria Zuleta Ferrari, who will stay three months to follow up on the cultivation process with the residents.

Because most of the soil in the neighborhood is composed of sand — which is both hard to cultivate and considered sacred, because it lies on top of a vast graveyard — off-soil, small-scale agriculture is the best option for the area.

“What is also interesting is that these gardens can be transported from one place to another, and can follow the residents even if the population is displaced,” adds Ferrari.

Elisabetta Bianchessi is an honorary member of the NGO and a professor of landscape architecture at the Milan Politecnico faculty of architecture. She explains that during the pilot project in November 2010, the NGO tried applying a technique that had previously been tested successfully in Senegal, but that did not fit the Cairene context.

“After this method proved unsuccessful, we spent the year looking for different amounts of components and vitamin solutions that would be more adapted to Cairo’s specific weather and environment, with successful results,” she stresses.

Building micro gardens

The main fruits and vegetables cultivated in the City of the Dead’s micro gardens are eggplants, tomatoes, peppers and strawberries. They were chosen after consulting the residents and considering the characteristics of the micro gardens, which don’t permit the cultivation of vegetables with long, vertical roots.

Liveinslums hopes the cultivation will eventually satisfy the community’s food requirements and represent an extra source of income for the area’s informal economy. According to the plan, each family’s garden will have from three to five boxes ranging in cost from 100–200 euros. The NGO covers all the costs, supplying the seeds, the layer of perlite and the vitamin solutions, as well as the tools.

Liveinslums is funded by the Universal Exposition, which will be hosted in Milan in 2015. The NGO not only helps build micro gardens and train residents to cultivate independently, but also plans to provide alternative solutions to reduce the costs of the materials and substances used for the mini-gardens, and to analyze the quality of the food grown in these transportable boxes.

Stefania Toso is an architect who participated in the workshop. With a small team of five, they designed a cover for the boxes that would both protect vegetables from bird and insect attacks and from heat that could ruin production.

The white nylon net prototype is applied on the boxes as a roller blind that protects the plants. Designers and architects say this should be replaced by a black nylon net during the hottest months.

“The interaction with the inhabitants is the best part,” Toso says. “Since the NGO has been working with the community for more than five years, the inhabitants know and trust the team. In contrast to the majority of workshops I’ve attended, this project is not only theoretical. We’ve interacted with the inhabitants and tailored the project around their needs.”

Although she does not think that theory is sufficient, it is still very important, and she deplores a lack of theoretical preparation for participants and NGO members. Some members suggest the project could be improved with more Arabic speakers to interact more efficiently with residents, and if the overall organization of the workshop was more structured.

“We would like local citizens to participate and help us,” Silvia Orazi, founder and director of Liveinslums, admits. “However, the stigmatization of the area has repelled many Egyptians who belong to higher social classes from participating in the project. The inhabitants of the City of the Dead often feel less judged by interacting with us, even though we don’t speak Arabic.”

Mohamed, a 27-year-old resident, is one of the few inhabitants who speaks English and easily communicates with the NGO’s organizers. He is excited about the project and interested to actively collaborate with its team.

“Contrary to my friends, I didn’t end up using drugs. I think in life we’re always offered a chance. And if the chance doesn’t come to you, you have to look for it,” he says. “Hopefully this is my chance.”