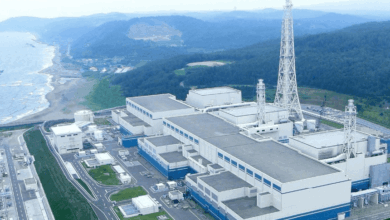

Japan's idled nuclear reactors could restart work if they pass the first stage of two-step post-Fukushima safety checks, the government said on Monday.

Still, without a timeframe for the tests, concerns remain about summer power shortages that could hurt the economy.

Last week's surprise announcement that the government would conduct stress tests alarmed corporate Japan and outraged some local authorities, who had been prepared to approve reactor restarts after receiving safety assurances from the government.

The first stage of the stress tests will target reactors which have already completed routine checks and are ready for restart. The checks will assess resistance to severe earthquakes and other events more extreme than those for which they were designed.

A second stage of tests will make a comprehensive safety assessment of all 54 of Japan's reactors, the government added in its statement.

Four months after the Fukushima Daiichi plant was smashed by a tsunami and began leaking radiation, only 19 of the country's reactors are running and if some do not resume operation, Japan could be without nuclear power by next April.

The disaster has also sparked a broader public debate about the role of nuclear energy in earthquake-prone, resource-poor Japan, which relied on atomic power for almost 30 percent of its electricity before the crisis.

"Safety and a sense of security are the top priority," Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano told a news conference.

"On the other hand, the government must fulfill its responsibility for a stable supply of electricity and is coordinating on this with relevant ministries … and will make every effort to secure (supply) in the medium and long term," he added.

Edano gave no precise timeframe for completing either of the two stages, but said they should be carried out speedily.

UNCLEAR TIMEFRAME

The new assessment scheme, which also lacks detailed procedures, did little to elucidate atomic safety policy for reactor-hosting municipalities, whose approval is by custom required to restart reactors.

"I'm afraid we are still in the dark as to what the government wants to do," said Shigenobu Oniki, vice mayor of the southern Japanese town of Genkai, home of Kyushu Electric Power Co.'s Genkai nuclear power plant. The government had seen two idled reactors at Genkai as prime candidates for the first restarts since the Fukushima crisis.

"We don't know what each stage will be like and what kind of checks will be involved. I think the government owes us an explanation," Oniki said.

Amid the drawn-out radiation crisis at Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima plant, credit ratings agency Standard & Poor's said, Japan's energy policy will likely remain unpredictable for some time, posing risks for the utility sector.

"Because the nation's energy policy forms the backbone of the Japanese electric utility sector's creditworthiness, we believe prolonged uncertainty could hurt the sector's credit quality," it said.

Shares in Tokyo Electric have tumbled 80 percent since the 11 March disasters, while Kansai Electric Power Co. and Chubu Electric Power Co., the next two largest power companies, have both lost 31 percent.

In a sudden policy shift last week, Prime Minister Naoto Kan – under fire for his handling of the nuclear crisis – said Japan would administer stress tests modeled on those conducted by the European Union after the meltdowns at Fukushima.

The move was welcomed by critics who say Japan's safety regulations have been too lax, but it also raised the risk of power shortages that could stretch into 2012, and hurt industrial production.

To avoid a power crunch, the government had been pushing for early restarts of facilities that have completed regular checks, but some local authorities said they could not give their OK until the government clarified its position.

Anti-nuclear activists maintained their opposition to reactor restarts. About 100 demonstrators marched on Monday into the government building of Saga Prefecture, where Genkai is located, and made their way near the governor's office, Jiji news agency said.

Kan has ordered a full review of Japan's energy policy, which before the March 11 disasters had aimed to boost nuclear energy's share of electricity supply to more than half by 2030.

He also wants to raise the contribution of renewable energy sources to more than 20 percent by the 2020s, and has made passage of a bill to promote such energy sources a condition for keeping a promise to resign.

The unpopular leader, already Japan's fifth premier in five years, survived a no-confidence vote last month by pledging to hand over the reins to his Democratic Party's younger generation, but has refused to specify when he will step down.