Abydos may not draw the same number of tourists as sites like Giza and Luxor, but it is nonetheless home to the remains of some of ancient Egypt’s most beautiful temples

As you step off the train and onto the platform in the small and uninspiring town of Ballyana in Sohag Governorate it is difficult to imagine that you are only a few kilometers from what was one of the most important religious sites of ancient Egypt. This area, which was known as Abdju to the ancienct Egyptians and Abydos to the Greeks, stretches across eight square kilometers of the Western desert near the edge of the floodplain. It contains the burials of the first pharaohs and later kings, noblemen and ordinary people in ancient Egypt.

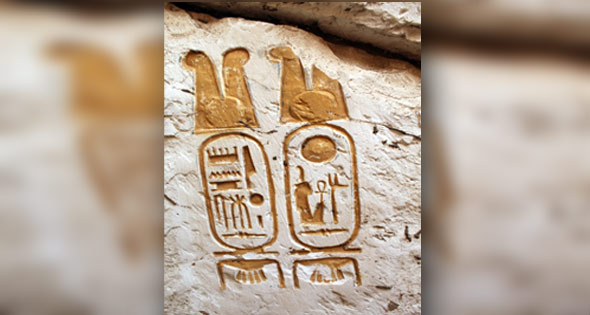

Abydos was also the center of worship for Osiris, the god of the underworld who controlled passage into the afterlife. Osiris was the protagonist in a battle with his evil brother Seth in an important myth that symbolized good and evil and saw the eventual prevalence of order over chaos. There is also the temple of Pharaoh Seti I, the father of the great Ramses II. The desert around this temple is scattered with hidden ruins that span 4000 years of history.

Abydos was continually occupied from the first settlements of the predynastic period well into the Coptic era. The site developed as one of the most important pilgrimage centers in ancient Egypt. It is no wonder that for over a hundred years archaeologists have continued to excavate here hoping to piece together this city’s extensive and untold history.

Religious practices at Abydos continue today, as modern revivalists of the ancient Egyptian religion continue to pay homage at the holy site and the temple of Seti I. Umm Seti, an eccentric Englishwoman, took up residence in Abydos in the 1980s. She claimed to be the reincarnation of a priestess who worked at the Seti temple and became the secret lover of Pharaoh Seti. Umm Seti dedicated her modern life at Abydos to worshipping the ancient gods, burning incense, and laying offerings in a re-enactment of the ancient rituals of this sacred city.

On approaching the site, dilapidated mud brick buildings stand on either side of the ramp leading to the Seti temple. Ancient inhabitants, who must have occupied similar mud brick houses, would have been eager to reside in such close proximity to a temple that they believed would bring them closer to the afterlife.

Beyond the temple the desert stretches on for kilometers with barely a structure in sight. But the site is hardly barren as modern Abydos is littered with an array of ancient temples, tombs, towns and chapels that testify to its long history. Only the intrepid visitor who ventures out further into the desert will realize this.

This diverse landscape is the subject of David O’Connor’s latest book, Abydos: Egypt’s First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris published by AUC Press. O’Connor is an Egyptologist who has been excavating and researching the site for over 40 years and his knowledge shows in the book. The book takes readers to the site and traces its development from royal burial ground during the 1st dynasty to its transformation into a focal point of worship of the god Osiris.

It was here at Abydos, O’Connor writes, that ancient Egyptians re-enacted the battle between Osiris and Seth in an annual ritual that began at the temple in Kom el-Sultan and ended at Osiris’s burial mound at Umm el-Qaab. A statue of the god was then ceremoniously buried, only to be was revived and returned to the temple in a representation of the ancient belief in renewal and immortality.

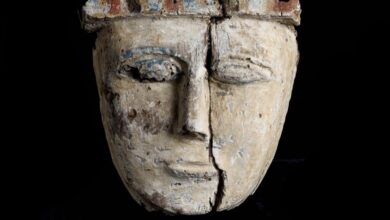

West to the area of Umm al-Qaab, the predynastic and early dynastic mastaba (flat-roofed rectangular) tombs of Egypt’s earliest rulers become visible. King Djer was buried here along with 325 of his servants and officials. In what was undoubtedly a gruesome scene, the king’s servants were killed after the death of the king so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife. This practice was later dropped, as shabtis (funerary figurines) became a suitable substitute.

But Abydos’s history is not all macabre. Tombs in the burial ground include some of the earliest evidence of writing, dating to circa 3300 BC. The mud brick structure known as Shunet el-Zebib also dates from this period. Shunet el-Zebib is a massive rectangular enclosure that rises up from the desert. O’Conner’s new theory suggests that these enclosures were associated with the tombs of the rulers and upon the rulers death, the enclosure was razed to the ground, symbolically transferred with the king to the afterlife.

Although Abydos was never a capital and the area ceased to function as a royal burial ground during the Old Kingdom, its religious significance as home to the burial place of the mythical Osiris kept it on the pharaoh’s map as a-place-to-build and on private individuals’ map as a-place-to-be-buried. A cemetery dating to the Old Kingdom contains tombs of prominent individuals from all over the country who were eager to be buried at the site’s sacred grounds.

During the Middle Kingdom, a large memorial chapel was established in front of the temple of Osiris. Here, people of all socio-economic levels erected stelas, inscribed commemorative stones, and built chapels dedicated to Osiris. These setups are reminiscent of today’s holy shrines of Sayida Zenaib, Sayida Nifeesa and others. Just like in ancient Abydos, these shrines attract crowds from across the country, who undertake the pilgrimage to offer prayers to the so-called saints in hope of receiving blessings for a better life.

Abydos may look different today but it retains much of its intrigue. Friends who have excavated here over the past few years and stayed in dig-houses located far into desert share stories of creepy noises and strange visions that appear during the night. Most of these stories make for a good laugh, but they accentuate the eeriness that comes with a plot of land that remained sacred to kings, gods and commoners alike for years.

It was only by the 3rd century AD, that the Roman Emperor Theodosius I ordered the closure of all pagan temples. With that came the eventual decline of one of the holiest sites of ancient Egypt. During the Coptic period, Christians erected a church in a small village to the north of Abydos following the same layout as the Seti temple. In a way, part of the Abydos tradition lives on.

The writer is an Egyptian archaeologist with experience in excavations around Egypt.

Life & StyleTravel