A man sits outdoors playing the rebab, singing a tale, and people start gathering around him, amused. Such is the typical image of the folk storyteller, in which the author is rarely known and each narrator down the line changes bits and pieces of the story, depending on his or her views and audience.

Shafika and Metwally ― Egypt's most popular story of honor, equally entertaining and devastating ― is a special case. Over the years, famous mawwal ― a traditional genre of music sung in colloquial Arabic and used in storytelling ― singer Hefny Ahmed Hassan has been seen as the tale's official narrator. But the story is overturned later on in a 1978 adaptation by director Ali Badrakhan.

The original story is set in the Upper Egyptian town of Girga at the turn of the 20th century, the folktale is based on the true story of Metwally and his prostitute sister, Shafika. The story had little success with the public until the Egyptian national radio service aired it every day in the wake of the 1952 revolution, mostly due to its emphasis on the power and honor of the new military class that had taken power.

Hassan begins the mawwal, creating sympathy for the protagonist, Metwally. Summoned to military service, Metwally is promoted to sergeant within six months. Metwally being an Upper Egyptian is no coincidence, as men from the south are synonymous in Egyptians' collective consciousness with robustness and virility. This is emphasized by Metwally joining the male-dominated and heroic military environment.

Representing military authority, Metwally slaps a soldier merely for being “loose” or “whimsical.” The “loose” soldier happens to be rich, so it's easy to despise him when he gets back at Metwally by showing him a photograph of Shafika as a streetwalker. This contrast between the working-class Metwally and the rich soldier serves the contrasting image promoted by the 1952 revolution.

What “breaks” the “manly” image of Metwally are Shafika’s actions that stain his honor. According to popular convictions of the time ― of which some traces remain ― a man’s honor also entails that of his kinswomen, legitimizing the idea that men should monitor the women in their families. And Shafika is given no possible excuse for her actions; her family is not poor and her behavior is portrayed as stemming from her loose nature. According to the mawwal, she is thus in dire need of a man to limit her freedom, which has been reduced to being represented by her sexual desires. Stripped of any identifiable characteristics ― there is no mention of Shafika before she becomes a prostitute and she is barely given a voice to speak in the mawwal ― Shafika comes off as a generic image of a woman needing male supervision.

She is only described as beautiful and sexually appealing, someone for men to use and abuse. When she finally speaks in the mawwal, her own words condemn her. She only gets three sentences, while Metwally repeatedly criticizes her actions throughout the story.

For Metwally, losing his “honor” is worse than death so he decides to kill Shafika, or rather slay her like a sheep. He then disfigures her corpse, erasing her source of power: her beauty and sex appeal. It is as if Shafika is punished twice: once for being a prostitute and another for being attractive. The disfiguration of the corpse is living evidence, a warning to all women who might think of defying the patriarchal social order. And a similar analogy can be made for the military's perceived authority over people who consider challenging its rules of governing.

Not only does society support Metwally, but the judiciary does as well. The judge in the murder trial concludes that Metwally has cut off the “rotten tree branch” (Shafika) to rescue the whole tree (his family and society at large). The mawwal ends by saying, “[Metwally] has truly honored his country,” leaving the audience remembering how correct Metwally was when he viciously slew and deformed his sister.

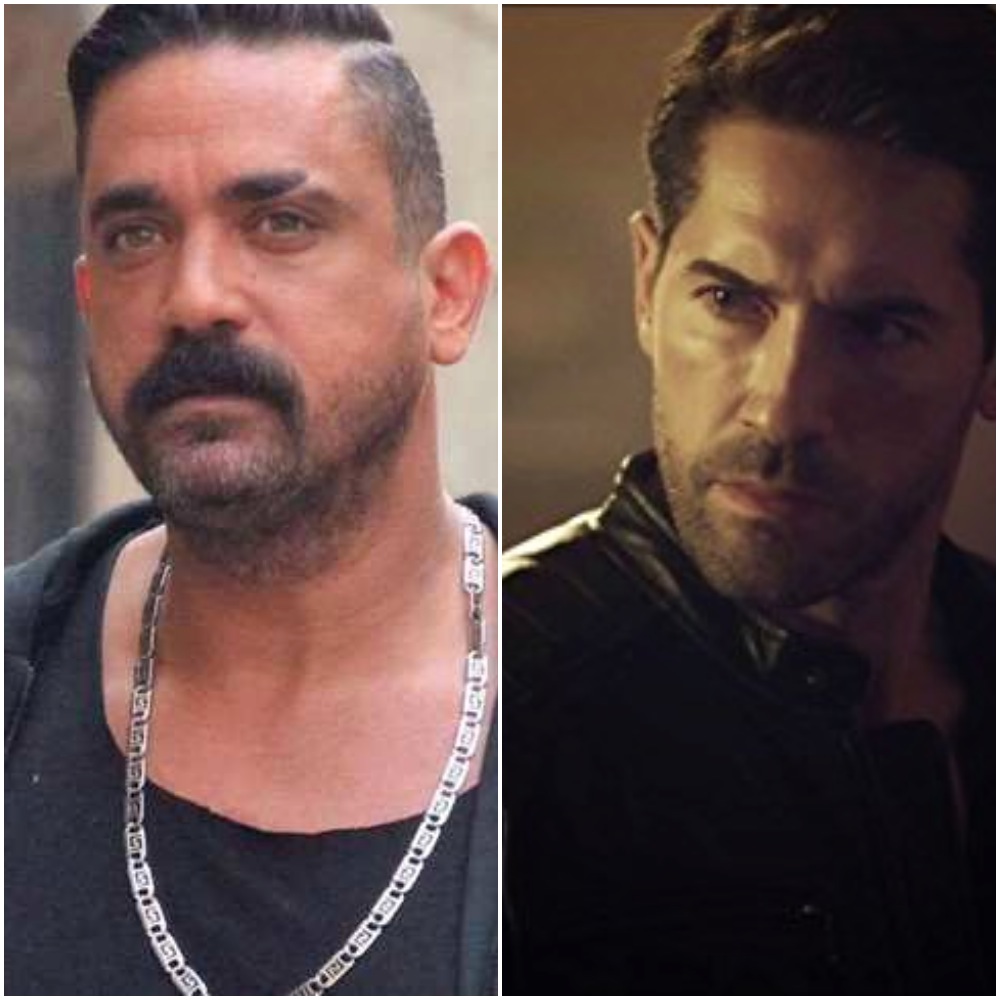

But in Badrakhan's 1978 adaptation, the story shifts significantly. Late Egyptian sweetheart Soad Hosny and iconic actor Ahmed Zaki, who star as Shafika and Metwally in Badrakhan's film, turn the tables on the traditional tale. In his version, Badrakhan argues against the idea of honor killing. Shafika’s work is justified because she is a poor and naive village girl. She falls in love with a man who uses her and then leaves her for money. In fact, her male “lover” works as a prostitute for an old English woman, overturning the notion of the importance of a woman’s chastity.

Metwally is also portrayed differently in the film. He is a laborer working on digging the Suez Canal for the British rather than a military officer. In Badrakhan’s adaptation, both Shafika and Metwally are victims of a system that eventually causes their deaths. The film was a great success and became an Egyptian cinema classic.

Perhaps nowadays the film has become even more popular than the mawwal. But Badrakhan can only be seen as one narrator among many who has added his own views to the timeless story.