In his seminal work Madness Explained, Richard Bentall suggests that through studying serious mental illness, namely psychosis, one taps into the overall human nature.

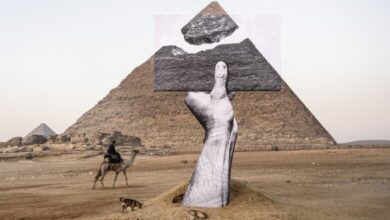

Artist and graphic designer Nermine Hammam takes a similar position in as much as she sees, within mental illness, a bigger picture of life. Her exhibition of art photography features a series of 77 digitally modified photographs based on mentally ill patients.

Through her photographs we see a strong human element against a background that elicits questions of marginalization, neglect and social incarceration. Some of the protagonists of the photos gaze at the viewer, inviting them into their world; some pretend the lens is not there and engage in the normalcy of their everyday life; and some just hide their faces. All draw us into the otherness of their world.

But this otherness, for Hammam, is a reflection of our own world. “When I used to see them murmur, it reminded me of my own brain. The minute you step out and look at your brain, this is what you see. Those people are a mirror.”

Metanoia builds on Hammam’s general interest in the alter state of the sub-consciousness, which was showcased in her previous works about mulid and ‘ashoura (Shiite commemoration of martyrdom of Hussein Ibn Ali, the Prophet Mohamed’s grandson). For Hammam, venturing into her subjects’ lives means going elsewhere and rediscovering reality under a new lens, away from the thought dictatorship people live under.

Hammam is also drawn to the cultural elements that make their way into this state of sub-consciousness. In Metanoia, she recalls how the local culture celebrates el-magzoub, the madman, by placing him in a super-human position. You touch him and you get blessed, goes the local saying.

Institutionalizing people with mental health problems only began here in 1883 when the government, under British colonization, set up the first modern hospital for the mentally ill in Abbassiya. It’s interesting how today, a new law calling for an end to the incarceration of the mentally ill in Abbassiya is based itself on Western modern traditions, according to which mentally challenged people should be socially mainstreamed. And it’s interesting how Egyptian society is roaring about the decision.

Hammam’s photographs interrogate these realities. As a medium, photography is part of this attempt to question reality and create a space of new possibilities. “A photograph is one 120th of a second. How many images can there be in a second? Which one is real? Where does it start and where does it end?”

Metanoia is a process of psychotic breakdown and subsequent positive psychological rebuilding or healing. Hammam says there can be a healing process in seeing another’s pain, and there is a measure of inter-connectedness between both mental illness and healing processes in the way she looks at her subjects.

Hammam describes the process of making her photographs using such phrases as “I enter my subject,” “You and them become one,” “It’s important they allow you to yield the picture,” and “For the first month I decided to take no photographs.”

“It was awful to try to hunt a picture. I brought long lenses and used to hide behind trees,” she says, from her creatively messy desk. “And then I found it to be abusive. The lens can be abusive. The decision was to either go for it or leave it. So, I put my camera aside and started building a relation. I went with my 12-year-old daughter.”

At one point, this socialization process became more intimate when one of the patients asked Hammam to hug her. “It was difficult for me. But once it happened, something broke. At the end they told me ‘You are the mad one.’”

This somewhat ethnographic experience remains incomplete, perhaps like all ethnographic interactions that pretend to penetrate the life of an “other” but which exit these lives once a product materializes. Hammam says she didn’t return to the hospital after the exhibition and does not have the courage to show the pictures to her subjects, as some of them have not seen themselves in 40 years and could be shocked.

The product of Hammam’s interactions is a photographic series with a highly aestheticized and somewhat poetic appearance due to Hammam’s digital intervention. She is frequently questioned and even criticized for her manipulation of her photographs, which is rather less evident in Metanoia in comparison with previous works.

Her aesthetically elaborate, painting-like photographs beg the question: Is she trying to play with, beautify, fantasize, romanticize or poeticize misery? “I enjoy doing it. I am not so sure I enjoy taking the photograph as much,” Hammam says, and then wonders why the art world is always anxious about her digital manipulation. After a few more thoughts about romanticizing, she says, “It’s like caressing the other, not aesthecizing a situation. The situation is grim. Maybe we heal ourselves through the other.”

Metanoia raises many thoughts through its multiple layers, from the specificities of mental illness to the generalities of understanding differences, questioning normalcy and re-exploring oneself in a new light.

Hammam’s photographs are discomforting, as an art process, as artistic products, and as subjective documentations of a reality. But who said that art must be about pleasing, rather than unsettling and afflicting the comforted? That’s the only way it can be a space of possibility.