Masoud Aqil’s longest incarceration in one place was in a soccer stadium in Raqqa, Syria, the Islamists’ stronghold at the time. He spent around 100 days there. Aqil survived a total of 280 days in six torture chambers. After being released as part of a prisoner exchange in September 2015, he immediately fled to Europe.

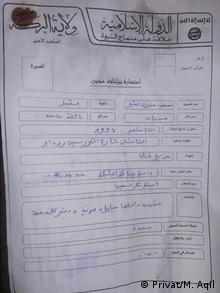

He’d had enough time while in captivity to become familiar with supporters of the self-styled “Islamic State.” In Europe he claimed to have recognized some of them — with concrete information on at least three men, and the names of dozens of others he researched online. In Germany he handed the resulting list to the police. Aqil spent almost two years working as a video journalist in Syria, a time he also discusses in the DW documentary “Masoud’s list.” He’s written a book about his experiences whose title roughly translates as: “In our midst: How I escaped IS torture only for it to catch up with me in Germany.” German intelligence considers information of this variety increasingly important.

Four in five leads genuine

Germany’s domestic intelligence service has set up a hotline that is also intended to reach informants from inside the refugee community. “We have received hundreds of tip-offs, some of them from asylum-seekers. We assume that many of them are genuine, and need to be followed up on,” says Hans-Georg Maassen, head of Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, in an interview with DW.

Maassen says that over 80 percent of tip-offs are serious information about potential terrorists as opposed to malicious smears. “We have one group comprising IS terrorists who have been instructed to conduct attacks in Europe; we have identified at least 20 individuals to date who, we assume, came to Europe with that intention. The other group are IS fighters who want to get away from combat activity and may be guilty of war crimes, and who now come here pretending to be asylum seekers.” As a result, perpetrators and victims now co-exist in refugee homes in Germany.

Tip-offs from refugee home

Aqil, a Syrian Kurd, says he spent months in refugee accommodation in northern Germany after arriving in the country in January 2016. He kept a low profile, but remarkably he claims to have recognized his torturers there. Guido Steinberg from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs is regularly recruited by German courts to assess refugees’ testimony. He says the information supplied by Masoud Aqil is no exception: “The exodus of refugees from northern Syria in 2014/2015 saw a lot people from militant groups including IS coming to Germany. There are many cases of Syrians living in refugee homes giving the authorities information about alleged and actual members of IS,” according to Steinberg. That said, the Middle East expert is more skeptical than the German head of domestic intelligence: “A considerable proportion of the tip-offs from refugees are deliberate and unfounded smears, which is why you have to be careful with the accusations being made,” Steinberg warns.

Read more: Number of potential terrorists in Germany on the rise, report says

Monitoring refugees

During the Cold War the foreign intelligence agency (BND) of what was then West Germany created a special section to collect tip-offs from refugees – then primarily from communist eastern Europe. The department’s agents worked in close cooperation with their American co-founders. After it emerged in 2013 that intelligence from the same department was being forwarded to assist US military drone operations – illegal under German law – the body was closed won. Domestic intelligence is now reintroducing active inquiries among refugees, with migration department staff now accompanied by intelligence agents. The 250 new jobs to be created by 2019 are, says agency chief Maassen, absolutely necessary.

Misinformation

The supply of information from refugees, however, has also been criticized — especially when it comes to Syria and Iraq. “It’s often a case of political interests,” says Wolfgang Kaleck, secretary general of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR). Kaleck warns against using such tips indiscriminately. Among the refugees, he says, are supporters of various parties to the conflict in Syria, “who, as in any war, will later have scores to settle.” The ECCHR is currently representing a former member of the Syrian military police with the code-name “Caesar,” who smuggled out photos of the torture prisons run by the Assad regime. The center has pressed charges in Germany on his behalf against high-ranking members of the Syrian police and intelligence agencies. Extensive research beforehand compared the photos with information from other sources. “Individual leads alone can also lead to innocent people being targeted by the authorities in Europe,” says Kaleck. “I also fear that opponents of immigration will exploit the fact that individual suspects do exist among the substantial Syrian community, even if the vast majority of refugees are themselves direct or indirect victims of violence.”

Masoud Aqil’s experiences as a victim of torture in Islamic State prisons have reinforced his conviction that, as he puts it, “fighting IS is a duty.”