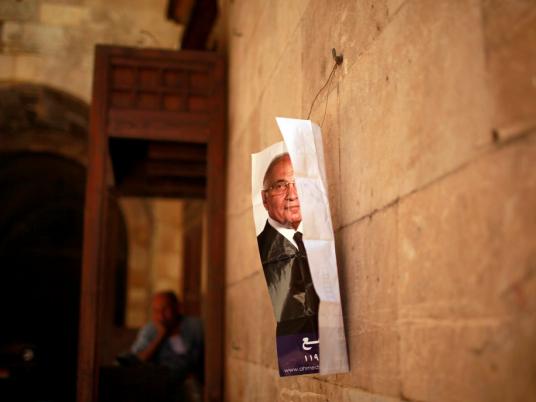

The decision a few days ago by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) to appoint Kamal al-Ganzouri as prime minister is a telling move. It is telling of the lack of imagination, and daring, of the council. It is telling of a state elite that can only accept one of its own at the helm, a man they understand will serve the state. "L'etat, c'est moi," said Louis XIV. "L'etat, c'est nous" seems to be the SCAF's motto.

One could think of no less apt a choice for the post at a time when hundreds of thousands are clamoring for more independent and visionary leadership. Ganzouri was prime minister between 1996 and 1999 and was known for his autocratic style, his tendency to micromanage government and his repression of the press and civil society.

To be sure, Egypt's generals had a choice to reach out to a political figure such as Amr Moussa or Mohamed ElBaradei, who have some street credibility and who would have demanded that they surrender at least some of their authority. Instead they chose to take out of the mothballs a man whose chief asset is that he is a faithful government servant, a consummate insider, and familiar with the intricacies of that great machine of state that, even before the revolution, had begun to fall apart. It is their hope that Ganzouri will keep this machine going, and probably their calculation that only men cut out of his kind of cloth can keep it under control and keep it chugging along.

Ganzouri is a career public administrator and economist who cut his teeth in government during the Sadat era. He briefly served as a civilian governor of the province of Beni Suef, a rare appointment at the time. Like Hosni Mubarak, he hails from Menoufiya, and became a minister soon after the assassination of Sadat, holding various posts until he became prime minister on 4 January 1996, soon after parliamentary elections were held. He was sacked on 4 October 1999, a few days after Mubarak won his fourth presidential term.

There exists a notion that Ganzouri was let go because he opposed Mubarak on several issues and had become a threat to the president. Like the idea that Amr Moussa's popularity as foreign minister was a threat to Mubarak, this is easily dismissible drivel: in fact, neither man ever took a public stance against the president and both of them faithfully endorsed Mubarak's policy choices, as the public record — as opposed to rumors and journalistic speculation — shows. One key factor did feed the rumors that Ganzouri had challenged Mubarak, though: after he left the cabinet, he was never heard of or seen again in the media until the day after Mubarak was overthrown.

The reason Gazouri was under quasi-house arrest all these years is not a rivalry with the former president, however. It was Ganzouri's autocratic micromanagement of his own cabinet and his attempts at castrating other ministers that caused a good part of the Mubarak regime to turn against him. This includes, most notably, various factions of the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP).

Ganzouri was a hyperactive, dynamic prime minister, passing more laws and launching more initiatives than any other premier under Mubarak. But he came from a tradition of central state planning and put a break on the reforms demanded by the structural adjustment plan that Egypt had adopted in 1991 at the urging of international financial institutions. He made enemies by scrutinizing privatizations, putting them under the aegis of a special committee that he himself chaired. He was particularly at odds with Youssef Boutros-Ghali, then Minister of Economy, and an advocate of economic liberalization. Ganzouri preferred mega-projects in which the state could guide development. The one most closely associated with his era is Toshka, an incredibly expensive attempt to divert water from the Nile into a "new valley" in the middle of the Western Desert that would alleviate the "old valley's" overpopulation. It was a dismal failure, and while Ganzouri is sometimes said to have privately opposed Mubarak on the issue, in public he said that "raising doubts about Toshka harms the interests of the nation."

Such grandstanding was common. Ganzouri's fall was probably attributable to the fact that many ruling party MPs loathed him, and that the feeling was mutual. In one particularly memorable incident in 1999, Ganzouri lashed out at MPs who kept interrupting his speech. Soon after, rumors of a new, more pro-business, ruling party to rival the NDP surfaced. Gamal Mubarak was believed to be close to this project, which was to be called the Future Party. This fight also extended to the media, where prominent journalists frequently attacked Ganzouri: Adel Hammouda, a veteran editor then working at the state-owned Rose al-Youssef, was reportedly sacked because of his critical coverage and wrote a book titled "Ganzouri and I." Finally, Egypt's then fledgling civil society also battled against Ganzouri, who — after being told by Mubarak that he was tired of complaints about human rights from Washington — launched an attempt to turn all NGOs into government-controlled entities.

Ultimately, Ganzouri's most important legacy may have been the liquidity crisis he left behind, which left public banks massively in debt after businessmen close to the regime took out favorable loans with little collateral (to be fair though, the crisis was exacerbated by the inaction of his successor, Atef Ebeid). It took until 2003 for the Egyptian economy to recover — and I would wager that his knowledge of deep state corruption was one of the primary reasons Ganzouri was removed from the public eye for all of these years.

Perhaps the most important thing about the Ganzouri appointment is that it brings back a man from a bygone era. Egypt is markedly different today from the 1990s, and not just because Mubarak has been overthrown. The country is more fragile, more exposed to the global economy, its institutions are failing and the public's trust in the state is at an all-time low for this historically centralized country. No doubt, Ganzouri is being brought in only for a short term, since there should be a new government in six months, if not after a new parliament is elected. What the SCAF does not seem to realize, politics aside, is that Egypt does not have that kind of time to waste.