Former President Hosni Mubarak was sent the same message in a variety of different ways: high quality posters, ragged cardboard, raised shoes, and chants. For 18-days, the ousted president belligerently clung on to the reins of power.

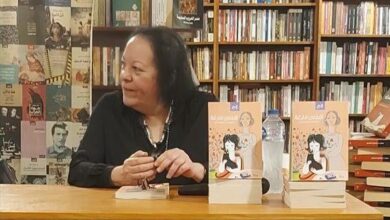

Mubarak is finally gone, but the messages remain, recorded for posterity in Messages from Tahrir, a book edited by Karima Khalil and published by the AUC Press, which showcases the work of 35 photographers from various backgrounds, many of whom were on the street to snap pictures as much as they were to protest.

Messages were painted, sprayed and printed on all types of surfaces: paper, cardboard, cloth, on people’s heads, their hands and, in at least on instance, on a shoe. They read “Go” in both Arabic and English. As interesting as the messages were, the people displaying them, a diverse cross-section of Egyptian society that was indicative of how widespread the movement was.

Khalil was present in Tahrir for 14 of those 18 days. The diversity of the protesters and the “eloquence” of their messages struck a chord with her.

“I felt that these largely handwritten messages expressed a multitude of long-suppressed yearnings,” she said.

Khalil ploughed through over 7000 images from the protests between 25 January and 11 February. Her initial criteria were the content of the sign and its emotive strength.

“I felt the images had to represent the range of emotions I saw in Tahrir: mourning, rage, anger, determination, pride, sarcasm, steadfastness, good humor and satire and ultimately, celebration as well as caution, and the book shows them in that order,” she said.

And represent they do. The language indicates a loss of fear that had dominated the Egyptian psyche for decades. One sign held by a man wearing a bike helmet said, “I’m not afraid of dying, Mr. President.” Another picture depicts a young man with a stern face. On his forehead is the word “leave” and his hand is splayed open to complete the message with “you oppressor.”

When Khalil met with some of the photographers to give them advance copies of the book, one, Rehab al-Dalil, began to cry as she sifted through the photos. The 21 year-old photography student said that the revisiting the period by perusing the pictures was overwhelming.

“It reminded me of those 18 days, they are some of my favorite memories ever and especially now that we’re in a very bad phase, those days mean more. In the pictures I saw people who were with me on 28 January, and I wondered if they were safe,” Dalil said.

“It was a hard time, but to be a part of history is an honor. You forget the tear gas and everything else,” she added.

One of the pictures in the book is of a young woman holding up a sign that reads, “How can you call him our father? Isn’t he the one killing our brother?” The 24-year old protester, Deena Saad Eldin, came up with the slogan herself and she made the sign in Tahrir Square.

“At that time, Mubarak had given his second speech which had swayed public opinion and people’s stance against the revolution, as people had begun sympathizing with him,” Eldin said. “A common remark at the time from people urging protesters to refrain from the Tahrir sit-in was ‘Mubarak’s like our father and we cannot ask him to leave.’”

“The picture was taken on 2 February after the ‘Battle of the Camel.’ I was trying to communicate to whoever believed in that ‘father’ concept that he could not be this father figure if he was murdering our brothers,” she added.

Proceeds from the sale of the book will go to al-Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence.

“During the difficult days that we are going through now as a nation, I feel it’s important to remember people’s aspirations in Tahrir and the great sacrifices that were made. I hope that this book can contribute in some small way to that collective memory and help keep it with us always,” Khalil said.