Upon entering the Arthropologie gallery in Zamalek, visitors are met by a SpongeBob character that leads them into the “Noodle Soup” exhibition. The art exhibition by Hatem Helmy is a crowded selection of collaged internet images, edited with Photoshop and printed on canvas.

In his prints, Helmy presents a disparate range of image combinations, all seeming to share the same absurd, yet somehow ironic, taste. In fact, the whole setting is ironic and hard to take seriously. Guided by SpongeBob, we walk through the show and are confronted with random objects, like an origami bird and a cardboard table in the middle of the gallery space.

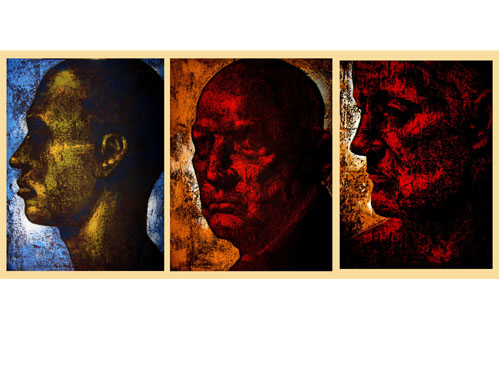

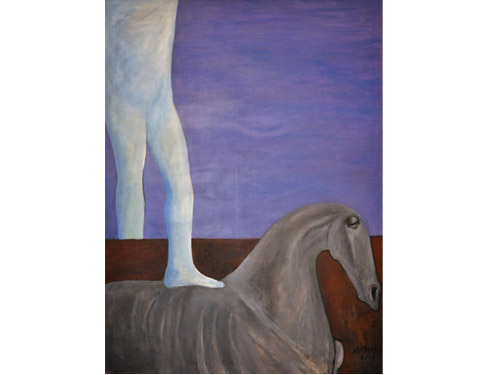

Helmy’s collages are overloaded with visual information. They range from the simple, like a Cairo urban landscape with modified color schemes, a profile of a young woman wearing a pendant earring made of an elephant and a microbus, and a belly dancing cat, to more sophisticated frames suggesting absurd little narratives. One canvas shows a waterfall crowned by a group of dolphins about to dive into the pond of human bodies below while a newborn child with silver shiny skin and an electric guitar tattoo is poised to jump in from the opposite side.

Some of the image associations present surreal settings or sexual metaphors made too explicit by the titles handwritten on stickers underneath each work. Others come off nostalgic for a generic ‘50s and ‘60s movie aesthetic with playful shape and color combinations.

Improbable prices are displayed next to each work, but the canvases are not for sale. In an adjacent room, cheap reproductions of the artwork, modified to host an advertisement in a corner, can be purchased for LE1. As the design suggests, the advertisements, for products like Nike and Marlboro cigarettes, are assumed to pay for producing the affordable prints.

Overall, the works’ combinations of imagery are visually stimulating at best, but too close to what we have already seen on the internet. Lately, other artists and designers have been working with similar materials and ideas, tackling questions of image repetition and circulation, the closest example in the Egyptian landscape being Amro Thabit’s graphic zines.

Moreover, the execution and the display of the works seem purposely careless, and a rather obvious question looms upon the one-room show: why decide to exhibit this kind of work in a gallery setting when its elements of fluidity and web aesthetics would be better served by these images remaining in the virtual dimension of the internet?

Too many aspects in “Noodle Soup” suggest that the point is not the artwork, and that what Helmy is trying to comment on is the possibility of showing art itself.

The artist confirms the doubt, saying that the whole show has been informed by radical absurdity and mistrust for the art world in general. Helmy reveals that the exhibition title has nothing to do with the show, as well as the titles assigned to the works and the strange statement published on all of the exhibition advertisement material.

Helmy spends few words on the creative process behind his pieces. First, he mentally assembles disparate visual elements through random image association, and then he searches for the individual components on the internet and Photoshops them together with no attention to the graphic result and the final image quality.

“All this does not aim at having any sense though, but just making fun of the artsy people,” Helmy tells Egypt Independent. “There is no point in showing these pieces I made […] and no reason why people would like them.”

When approached by visitors who ask for his signature on the back of the image copies on sale, he signs and comments on the absurdity of the request.

“I am not an artist,” declares Helmy. He says he is not interested in the art world “where everything ends up being dogmatic and has to be evaluated,” possibly referring to the somewhat problematic system through which art spaces, institutions and markets decide on what is to be shown to gallery visitors.

If these are the premises and “Noodle Soup” is just a critique of the art world and market dynamics, then Helmy’s criticism is sterile, mannerist and a bit pretentious.

The art world is full of examples of reflections and analyses on what can and what cannot be shown, and in which context. In this respect, “Noodle Soup” is far from groundbreaking. Artists from all over the world, from Marcel Duchamp on, have been looking into these questions with witty and arguably more powerful critiques, as they come from art makers exploring their own practice.

Helmy’s work on the other hand seems like a cynical statement that does not open a conversation but annihilates the questions it is trying to raise. His approach is too literal; he does not refer to himself as an artist and his disinterest in the practice hints at a total disengagement from it, so why even bother putting together a show?

The “Noodle Soup” exhibition opened on 29 June and can be viewed until 1 July at the Arthropologie Gallery, 13A Marashly St., Zamalek, Cairo.