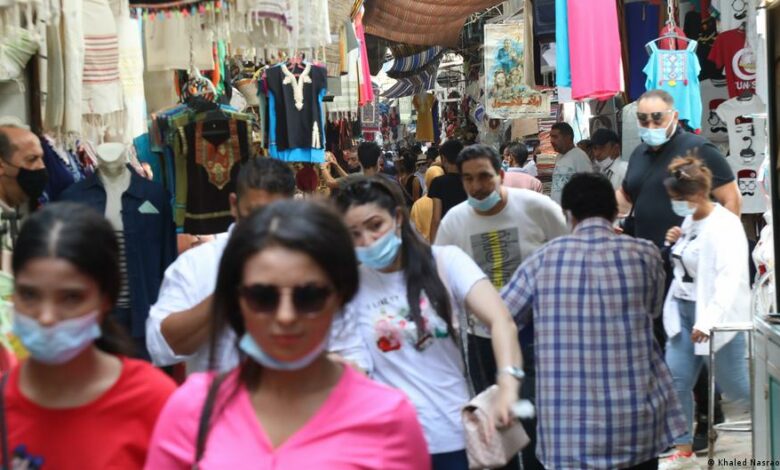

Wadi bin Soleiman taps at his mobile phone. He’s sitting on his chair, inside his ceramics store in the historic old city of Tunis, the capital of Tunisia. The market is usually a focal point for tourists. But it’s shortly before midday and bin Soleiman has yet to get a single customer.

Like so many other Tunisians involved in the tourism sector, bin Soleiman is fighting for financial survival. The COVID-19 pandemic has virtually brought international tourism, which employs an estimated 10 percent of the population here, to a standstill. In 2020, tourist numbers plummeted by almost 80 percent.

In order to keep his business going, bin Soleiman has had to use his savings. He’s been in the business since 1969, so long that he doesn’t want to simply give up. He has his own workshop that manufactures the ceramics he sells. He sees keeping the business afloat as a way to honor the memory of his father, who died in 2018. The elder man had run the business for almost 50 years.

Insecurity rules

Business hasn’t been easy ever since the Tunisian revolution in 2011, bin Soleiman told DW. And after Tunisian President Kais Saied suspended the country’s parliament for 30 days, around a week ago, those feelings of insecurity have grown again. Bin Soleiman says he has absolutely no idea what will happen to Tunisia’s all-important tourism sector now, faced with this latest political unrest in addition to the ongoing health crisis.

“This crisis started when my father was still alive,” bin Soleiman said, referring to the Arab Spring-era revolution of 2011 that toppled Tunisia’s dictatorship. “Then in 2015, there were terrorist attacks on tourists on the Tunisian coast and this too had a bad impact on our business. And now we have the pandemic, so we are fighting to survive once again.”

“I’m trying to see if I can earn money from other areas,” he explained. “I have two employees and both are married with children to support. I can’t let them go. We are all looking into the future together and we all have to make sacrifices.”

State of emergency

Bin Soleiman is one of the luckier businesspeople here — his store still exists. Many others have been forced to close, or are dealing with stacks of unsold stock that they cannot pay for.

Tunisians in other areas of the economy are also suffering. Tunisia’s gross domestic product (GDP) shrank an estimated 8% last year and thousands of jobs are under threat. Some of this economic frustration is being expressed as resentment of the country’s political leadership, something that was particularly evident on July 25, a public holiday known as Republic Day that celebrates the end of the Tunisian monarchy in 1957.

That day, locals demonstrated on the streets and again expressed their anger. And that evening, President Kais Saied declared a state of emergency to last for 30 days, with an option for extensions if needed. Saied’s supporters took to the streets, to cheer the decisions.

One of those celebrating was Lotfi al-Gharbi, who also usually earns his money here in Tunis’ historic center. “They have destroyed the country,” he told DW, as he crafted a copper platter. “I don’t have any ideological bias but since 2011, the Ennahda movement and their allies from the different political parties have pushed us into ruin. To support my family I need to earn at least a thousand dinars (€300) every month. But for years, I’ve only really been able to make about half of that. Who brought us to this point?”

No systemic reform

A lot of other Tunisians share al-Gharbi’s hardship. A recent study, undertaken by three different organizations and published by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Tunis, confirms this. The report, named The Dignity Budget for Tunisia, concluded that ordinary Tunisians need to earn at least 2,400 Tunisian dinars (about €750) a month in order to cover the needs of a family of four. However, the average wage in Tunisia for somebody working 40 hours only comes to about 430 Tunisian dinars (€130).

The economic problems in Tunisia have impacted all of the country’s various sectors, Omar el-Oudi, a local financial analyst and editor of the economics website Il Boursa, explained. The state has tried to support the tourism sector —which contributes around 14% to Tunisia’s GDP — with tax relief, by deferring debt and offering softer loans.

“These measures gave the sector some breathing space between 2017 and 2019,” al-Oudi said. But, he added, the structural problems continued because of, for example, frequent changes of government and politicians’ tendency to focus on localized solutions rather than far-ranging and systemic reforms.

A new dictator?

On top of all of Tunisians’ present woes, come the recent moves by President Saied. His opponents have described the president’s move as a “constitutional coup,” accusing him of endangering Tunisian democracy.

President Saied has a program that differs from those of Tunisia’s opposition political parties, building contractor Abdul Razzaq al-Akaishi told DW. He was one of those who went to demonstrate against what his president did.

“With what he’s doing, Saied will be popular mostly with the country’s disaffected youth,” he explained. “They are desperate for somebody to rescue them from the difficult situation they are in. But that doesn’t justify a coup against democracy and monopolizing state power. That is the behavior of a dictator.”

Should President Saied continue to behave in this way, then those who oppose him will likely protest on the streets again, al-Akaishi suggested. “And there are a lot of people who oppose him,” he said.

Back in the historic central city market, ceramics-maker bin Soleiman said he doesn’t have much hope that things will improve in the near future, not even if the health crisis is somehow overcome.

“The level of corruption is too much for this,” bin Soleiman concluded. “The things we have seen here since 2018 beggar belief. We basically need to take care of ourselves.”