Coming up to the former Hotel Viennoise on the third floor of the ramshackle but very grand and spacious 7 Champollion Street, there are blue, red, and gold hand-painted wooden signs advertising the “Studio Viennoise — by appointment only.” They are a charming beginning to an absorbing interactive exhibition about portrait photography in Egypt, “On Photography, at Studio Viennoise.”

The show has an emphasis on downtown Cairo’s old photographic studios, and the often Armenian families and figures who ran them. A “living studio” recreates the bygone experience of getting a special photo taken of yourself, and there is a large collection of photographs dating from the 1940s to now, memorabilia, old cameras, and video testimonies.

Organizers Heba Farid and Paul Ayoub-Geday of CULTNAT’s Photographic Memory of Egypt project have gathered photographs from private collections and studio archives. They have put together a label for each image that indicates the photographer, date, location, medium, and to whom it belongs, as well as reproducing any caption it bears. They have also interviewed various relevant people about vanishing aspects of photography – such as a camera repairman in Port Said, photographer Adel Atta of the still active Studio Venise, and a portrait photographer whose studio is a beach in Alexandria.

The Hotel Viennoise, built in the 1910s, gives all the exhibitions it hosts an atmosphere of dark faded grandeur, and that definitely suits the earlier photos in the show. The space has been cleaned up just enough — peeling paint and stained floral wallpaper remain. The lighting and videos (which are all happily short) are very simply installed. The mismatched frames of the photographs emphasize that they have only been brought together temporarily.

For “Studio Viennoise” itself, visitors need to check the schedule of the 10 photographers who will be working and make an appointment. The styles of portraiture vary. At one end of the spectrum is the old-fashioned, with Adel Attia (who learned from Van Leo himself and built his own equipment) and Katrine Dirckinck-Holmfeld (a Danish artist using a residency at the Townhouse gallery to re-stage Armand photos of celebrities and weddings from the 1930s to the 1960s). On the other end, Keith Lane is using an iPhone and David Maher is creating campaign posters, complete with logos and slogans, for visitors who fancy themselves as parliamentary candidates.

People can rediscover what it’s like to have to wait their turn for a photograph, have a personal encounter with a photographer, and then wait a few days to get the print. All the prints will be shown at the exhibition’s vernissage on 16 December, but a few have already been added to the show.

On the walls of the waiting room, complete with an old-fashioned desk and desk-lamp, are hand-signed cinematic photographs of cultural personalities and ordinary people by Alban (Aram Arnavoudian), his wife Chake, and Selim Yousef from the 1940s.

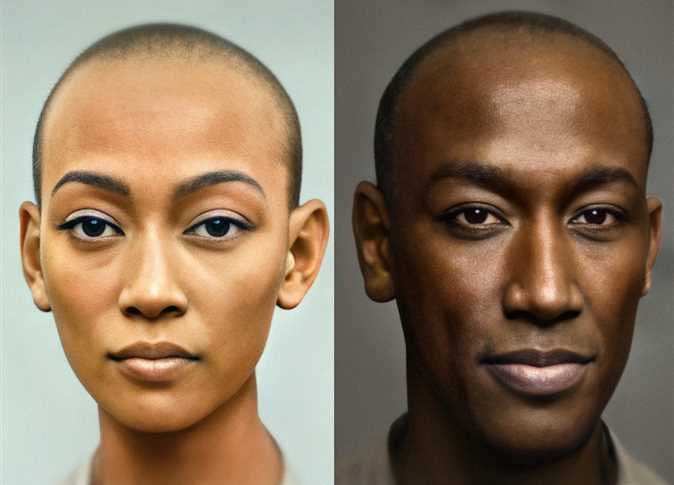

In the studio, you can step around bits of equipment to look at photographs by Van Leo (Levon Boyadjian) and Studio Bela (run by a Hungarian who apparently went by the name of Mr Bela) from the 1950s. Other rooms continue the chronology, and eventually we get large double portraits mounted on foamboard produced by a studio called Moments, in Alexandria, this year. Brightly colorful and much more ambitious in terms of scenarios than their 1940s counterparts (one couple are underwater, another hold surreal props), they appear nonetheless to be equally influenced by contemporary cinema — in this case, maybe Egyptian comedies.

A section of corridor is taken up with small snapshots, stuck directly onto the wall, of where the studios were — or in a couple of cases — still are: on Sharif Street, Qasr al-Nil Street, and Talaat Harb. Nearby are some photographs of Van Leo’s flat, taken by Barry Iverson after he died in 2002.

Another room is devoted to anonymous portrait photographers who work on the street, and the three-legged box cameras they (mainly used to) use. These “water cameras” (“camera mayya”), probably named as such because of the developing chemicals held inside and the accompanying bucket of water used to rinse the prints, are represented in photographs, actual examples of the cameras, and a great one-minute video by Ayoub-Geday showing the process. They are remarkable objects: often with photos stuck to the side, rags hanging off, dripping, sometimes handmade like the one in the video must be — bristling with nails and crusted with paint — some look more like contemporary sculptures than cameras. Examples of “camera mayya” photographs by the Canadian Chris Langvelt show what the results look like.

It would have been interesting to have even more information about the photographs in the exhibition. The labeling is only in English and sometimes vague — giving only the decade as the date and titles like “a collection of group portraits.” And perhaps not all the photographs shown are strictly relevant, such as Iverson’s hand-painted photographs of buildings in Cairo. But the haphazardness adds to the charm — the show feels like a labor of love.

Looking at the studio portraiture is like looking through someone’s old family albums, albeit particularly glamorous ones. There is also the little thrill of coming across celebrities, funny fashions, places you recognize, or people who look like people you know (some small portraits of soldiers from the 1940s look like they could be the soldiers you see now on the streets of Cairo). There is nostalgia for a more cosmopolitan past, before the foreign communities left, and there is nostalgia for the old techniques — “now there is no art involved” says Viken Antanick of Studio Anto, in one of the videos. But mostly it just seems cheerfully celebratory, unpretentious, and unintimidating.

A photograph “must always hide more than it discloses,” as Susan Sontag pointed out in her book “On Photography.” This is never more true than in studio portraiture: what we are seeing is obviously what people wanted to look like. But the exhibition attempts to show some of the context and processes as well as just the look of the final photo, and that’s what makes it good. That’s why the “living studio,” the “camera mayya” section, and the video testimonials — especially one in which Chris Mikaelian talks about watching Chake at work — are the most interesting parts. There is also a program of talks and screenings that is still being planned, which may add further context.

A highlight of the show is a series of four quite hilarious pictures taken by Antro, in which he is in the process of taking pictures of important figures. Testing the light with his light meter, he has to stand right next to his subject. Popping up behind the late Pope Shenouda in full regalia, next to a smartly uniformed Sadat who is already rigidly posed and has a zoned-out look on his face, squashed into the photo beside an uncomfortable and melancholic looking general, his smiley or concentrated face, the spontaneous inside the staged, gives you a glimpse of what studio portraiture is all about.

Images courtesy of Heba Farid